If you’ve been reading this column in recent months, you’ll probably remember an article, ‘‘The Language of the Wind” [We’ll go and find that one for you. —Ed.] that explained how to describe changes in wind direction and velocity. At the end of that piece I promised to present, in the next month’s issue, some rules of thumb for using those changes in the wind to get around the buoys quickly. Well, I got sidetracked in Fremantle, and that column was temporarily put on hold. But here are my thoughts on how to play the odds whenever the wind is shifting (which is always).

Windward Legs

Finding the fastest path to the weather mark requires studying the wind before and during the race to find out how it is changing. As far as wind direction is concerned, there’s one important thing to figure out: Is the wind oscillating (phasing back and forth), or is it shifting persistently in one direction? As we’ll see, your strategy will be very different in each of these conditions. Let’s look at some rules of thumb.

1. Tack on the headers

In an oscillating breeze, almost everybody knows you’re supposed to tack on the headers. Your goal is to stay on the lifted tack so you sail as straight (and as short) a course toward the windward mark as possible. This isn’t always as easy as it sounds, of course. Before the start, I like to sail as long as possible on each tack and watch my compass. This gives me a good idea of the high and low headings on each tack. Let’s say my headings on starboard range from a low of 240 to a high of 270. I usually take the average of these (255) as my median heading. Then I use this to play the shifts on the beat. If I’m steering 245, for example, I’m 10 degrees down from the median, so I’ll tack to port. If I’m heading 260, I’m slightly lifted, so I’ll continue on starboard.

2. Keep off the laylines

The laylines are definitely a dead end when the wind is shifting. If you get lifted, you will overstand and some of the boats to leeward may fetch the mark ahead of you. If you get headed, the boats to leeward and ahead will tack across your bow, while you have very little room to tack on the shift.

3. Stay on the tack that takes you closer to the mark

This is another general rule for an oscillating breeze. Sometimes you won’t be sure whether you are on a lift or header. In that case, get on the tack where your bow is pointing closer to the mark. After all, your object is to sail in that direction as quickly as possible. This rule of thumb goes hand in hand with another rule: When in doubt, sail the longer tack first. Unless you are dead downwind of the mark, you will have to spend more time on one tack than the other to get to the mark. There are two benefits to sailing this tack first: 1) It is more likely that it’s the lifted tack, and 2) it will head you toward the middle of the course, where you’ll have more room to play the windshifts.

4. Go in the direction where you look good

If you don’t have a compass or if you have a hard time reading windshifts on your compass, there’s another good way to play oscillating shifts upwind. Watch the boats all around you and sail in the direction where you begin to have a relative gain. For example, if the boats on your weather hip start aiming at your stern, you’re being headed and should tack toward them. Stuart Walker has a similar philosophy for playing an oscillating breeze. He says you should “Cross ‘em when you can?’ At the same time, “Don’t let ‘em cross you!” What he’s saying is that when a windshift puts you ahead of another boat, you should take that windshift across the bow of the other boat to consolidate your gain. If other boats are suddenly crossing your bow, tack to leeward of them and wait for the next shift in your favor.

5. Sail toward a persistent shift

As I mentioned above, it’s always important to decide whether you’re going to play the windshifts as oscillating or persistent. When the wind is moving steadily in one direction, your strategy on the beat changes completely. In these conditions, you can’t simply tack when you get headed. You have to keep sailing deeper into the header so you get as much benefit from the shift as possible. Don’t worry about other boats crossing you. In a persistent shift, taking some sterns is often the best catch-up strategy. Just be sure that you don’t get to the layline too far from the mark; if you do, you will likely overstand as the wind continues to shift.

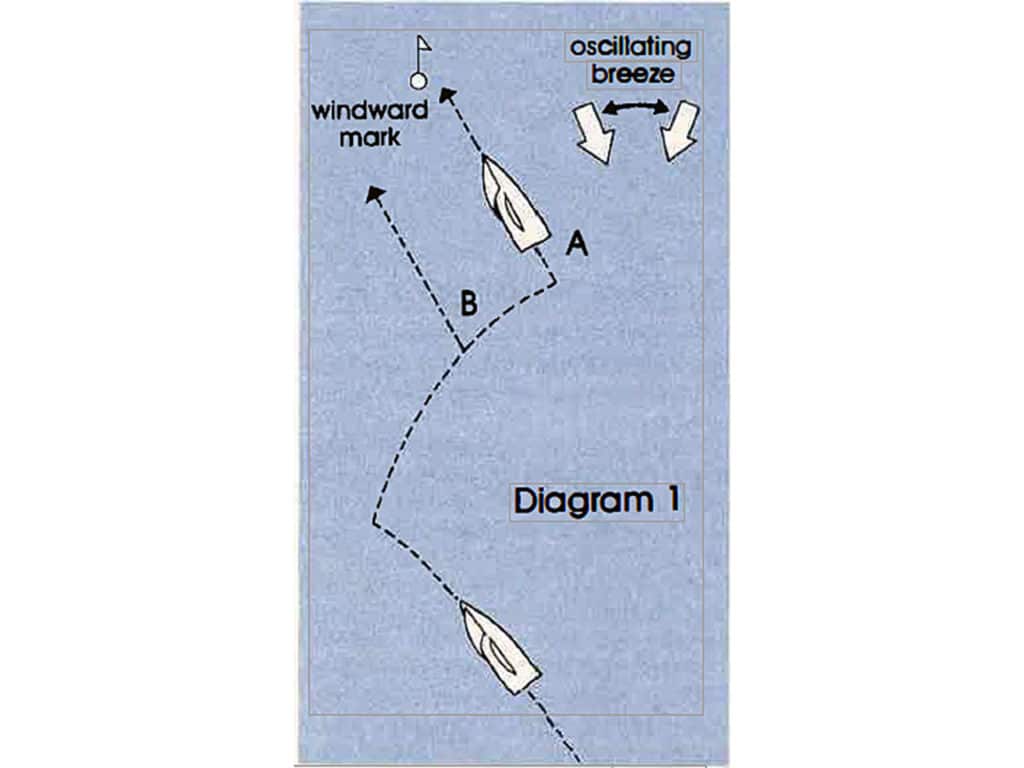

6. When you get close to the mark, play oscillations like persistent shifts

Even in an oscillating breeze, there is a point near the windward mark where you have to play any shift like a persistent shift (Diagram 1). Here’s why: Let’s say that on a given day each oscillation takes about four minutes. When you get within four minutes of the mark, you’re only going to have one more shift, so you must play this like it is a persistent shift because by the time it shifts back the other way, you’ll be around the mark.

Downwind

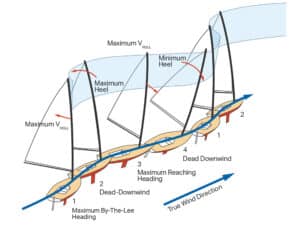

1. Jibe on the lifts

Upwind you tack on the headers, downwind you jibe on the lifts. The object on a run is to steer a course that keeps the boat going fast and aimed close to the mark. You can do this by staying on the headed tack as long as possible. This is a little harder than staying on the lifts upwind because the downwind groove is more elusive; it’s also harder to keep track of shifts downwind. Just as with upwind sailing, however, you want to stay away from the downwind lay lines and keep on the jibe that points you closer to the mark.

2. Sail toward the puffs and stay in them as long as possible

It’s important to play the shifts downwind, but often it’s even more critical to go for the puffs. There is nothing that will let you sail lower and faster than a good blast of air, so someone on your boat should always be looking behind to see how you can get to the best air. When you get into a puff, square your pole, ease the main, heel the boat slightly to windward, and bear off with the breeze. Not only will this let you steer more toward the mark, it will keep you in the puff longer.

3. Sail away from persistent shifts

When racing upwind, you want to sail straight toward a persistent shift. On a run, however, you should take your first jibe away from the persistent shift. This allows you to sail on both jibes in relative headers, which will bring you to the leeward mark faster. Just as when sailing upwind, be careful that you don’t go too far before jibing or you will overstand as the wind shifts. The only exception to this rule of thumb is when you have a persistent shift that fills in stronger on one side. When this happens, it’s usually better to head straight for the increased velocity.

The reaches

The effect of windshifts or puffs on a reach is usually less obvious than on a beat or run. The reason is that all boats are able to sail straight for the next mark, no matter what the wind does. There are ways, however, to take advantage of changes in the wind and increase your speed down the rhumbline.

1. Sail up and down in shifts and puffs.

Most sailors know you should sail low in the puffs and high in the lulls to maintain speed. It’s not uncommon for a boat’s course to vary as much as 20 or 30 degrees on a puffy reach. The same is true when the wind is oscillating. Keep track of the wind, and try to maintain roughly the same apparent wind angle down the reach. In other words, sail slightly high of the mark when you’re on a lift, and slightly low of the mark whenyou’re headed. In shifty and puffy winds, a sort of zigzag course can get you there faster than sailing a straight line.

2. Sail a low arc in breeze that’s dying or persistently lifting

There are two times when your best strategic move is to sail low on a reach. The first is when you have a dying breeze. In this condition, get low while you have breeze to take you there, and save your higher heading angle for the second half of the leg when the breeze is lighter and you need more speed. The second time to go low is when you’re being continuously lifted. Sail low early (in a relative header) so you can head higher later and maintain speed even though you are lifted.

3. Sail a high arc in breeze that’s building or persistently heading

This is the converse of the conditions for sailing low. Basically, if it looks like you will be headed or if the breeze will increase as you sail down the reach, go high and fast early in the leg; changes in the wind will help you get down to the mark later. Of course, there is no hard and fast rule that will always work in any aspect of sailboat racing. That’s one of the things that makes our sport a challenge. But with experience, you can identify a number of general rules, such as those above, that will work more often than not. Once you do this, then all that’s left is playing the odds.