A 25-knot wind streaks across Ivanpah Dry Lake on this cold March afternoon in California, dust whipping across the racecourse ahead. I’m having trouble relaxing my breathing. Maybe it’s nerves. Maybe it’s the 30-pound sack of lead duct-taped to my chest for extra weight. I’m about to start my first dirt-sailing race at the 2022 America’s Landsailing Cup, and I’m hoping this extra weight will help keep my Manta TwinJammer—or rather my lawn chair with a sail—on all three wheels.

Thirty of these 105-pound aluminum craft with bench seats crowd the starting line, which is a 100-yard piece of rope stretched perpendicular to the wind from the starboard side of the race-committee trailer. My competitors look like Mad Max dragoons, their identities masked by helmets and ski goggles. Their jeans are caked with dirt, some of them wearing motorcycle armor. While we wait for the previous fleet to finish, there’s a strange pre-start shuffle. Unlike the regimented starts of DN iceboats I’m more familiar with, where half the fleet starts on starboard and the other half on port, land-sailing starts are a free-for-all.

Everyone lines up on starboard in whatever position they like, and for the next 10 minutes, competitors walk their boats into openings on the line, repositioning and relocating for more space, but mostly crowding on the favored end. I decide to play it safe and start in the leeward third of the pack. I want to be able to get this three-wheeled vehicle ripping before beating my way up to the mark.

“I wouldn’t start there,” I hear one competitor say to another. “I’m going to roll right over you before you have time to blink.”

A woman bearing a green flag on a stick strides to the front of the race-committee trailer and holds it to the wind, at which point I overhear someone say: “I hope you guys brought extra underwear. You’re going to need it.”

Before I have time to exhale, the woman whips her flag through the dust, and I use the heels of my feet to crab-crawl my boat into action, Fred Flintstone-style. I’m no match for my pre-start adrenaline, and I mistakenly pull in my mainsheet too quickly. My windward tire goes off the ground and I’m two-wheeling. I ease the sail, the tire plops to the hard-packed mud, and I’m instantly eating everyone’s dust.

I finally manage to get my boat moving forward for a good 15 seconds, when a competitor to windward starts two-wheeling, veers downwind, and plows straight into the side of my boat, bending my steering bar. After making sure I have all my body parts and slinging a few choice words, we untangle and I sail toward the left-hand side of the racecourse. My only hope is to bang the corner, which ends up paying off when a gust surges me into the middle of the fleet.

Maneuvering up the course is a blur of kamikaze ducks and crosses, boats weaving through each other’s dust trails. I manage to duck one boat the way I would in a dinghy, mere inches separating my front tire from its stern, which is far too close for any sane person to attempt.

Yet sanity and dirt-boat racing seem mutually exclusive at times, and as I round the weather mark, I feel the full force of the Manta Twin’s speed howling downwind near 60 mph. On downwind legs of the course, the windward boat has right of way, and when one particular gust hits, I yell as loud as I can to a pilot below me to let me turn down to depower the sail. We both snake to leeward accordingly, though soon he’s a speck on the horizon.

The pack spreads out, and when I eventually bear away to cross the finish line, another gust hits and I capsize just to windward of the race committee, plowing over a set of traffic cones. Surprisingly, this moment is not as violent as I thought it would be. Most capsizes happen at low speeds, and unlike other land yachts, Manta TwinJammers have seat belts.

“You OK?” someone asks.

“I’m fine,” I reply, apologizing for tipping over on top of them. “It’s OK,” they say, sensing my embarrassment. “We just had a 38-knot puff roll through.”

Whereas iceboat racing’s redline is somewhere around 20 knots of wind, dirt boats can handle much more. “The deciding factor is the dust,” says Dennis Bassano, the North American Land Sailing Association’s race director. “If the dust is low, we’ll race in up to 30 [knots]. But if it’s really dusty and we have a lot of boats, we’ll call it off at whatever speed it is because no one will be able to see at that point.”

Bassano has an easygoing personality that he conceals behind a hardened exterior. Having organized this event for more than 15 years, he’s used to being a hard-ass when the situation calls for it. Before he took over, the typical racetrack featured six or eight turning marks and more than 40 different course configurations. They had a numbered start system and courses featuring both port and starboard roundings, as well as reaching legs and other quirks that were confusing for even the most experienced competitors.

“When I took over, we went to modified windward-leewards, with either port or starboard roundings depending on the wind direction,” Bassano says. “Everyone can start where they want, and instead of a set number of laps, we do a timed race, so whoever does the most laps in the allotted time wins. This way, you don’t have to wait 30 minutes for stragglers to finish.”

To score these races, each boat must pass through the finish line every upwind leg so the race committee can count laps, which can get confusing quickly with 30 Manta Twins zipping around the racecourse.

Scoring isn’t the only unique aspect of land yachting. Instead of a mark-set boat, the race committee uses a pickup truck, which is the only vehicle allowed on the lake bed itself. The regatta’s command center is a trailer at the center of the race village, which consists of a long and orderly row of campers, trucks and RVs.

Even though land sailing began and remains popular in the tidal beach towns of northern Europe, the American scene is naturally more rugged and individualistic. Regattas take place on the dry lake beds of America’s Western deserts, forcing competitors to travel long distances to camp in the middle of nowhere. Ivanpah Dry Lake crowns the northern edge of the Mojave National Preserve on the border of California and Nevada. Over centuries, this area has hosted many a wayward pilgrim, a tradition still alive as land sailors from every corner of the union haul their rigs across the country to set up shop for a week. Some pilots bunk at the resort a few miles north in the border town of Primm, but most camp on the playa itself. When the mornings are still, the air fills with the sound of impact drivers and fairing tools. The aroma of bacon grease hovers over the sagebrush, and laughter echoes out from campsites. The camaraderie is ironclad, but factions have developed over the years.

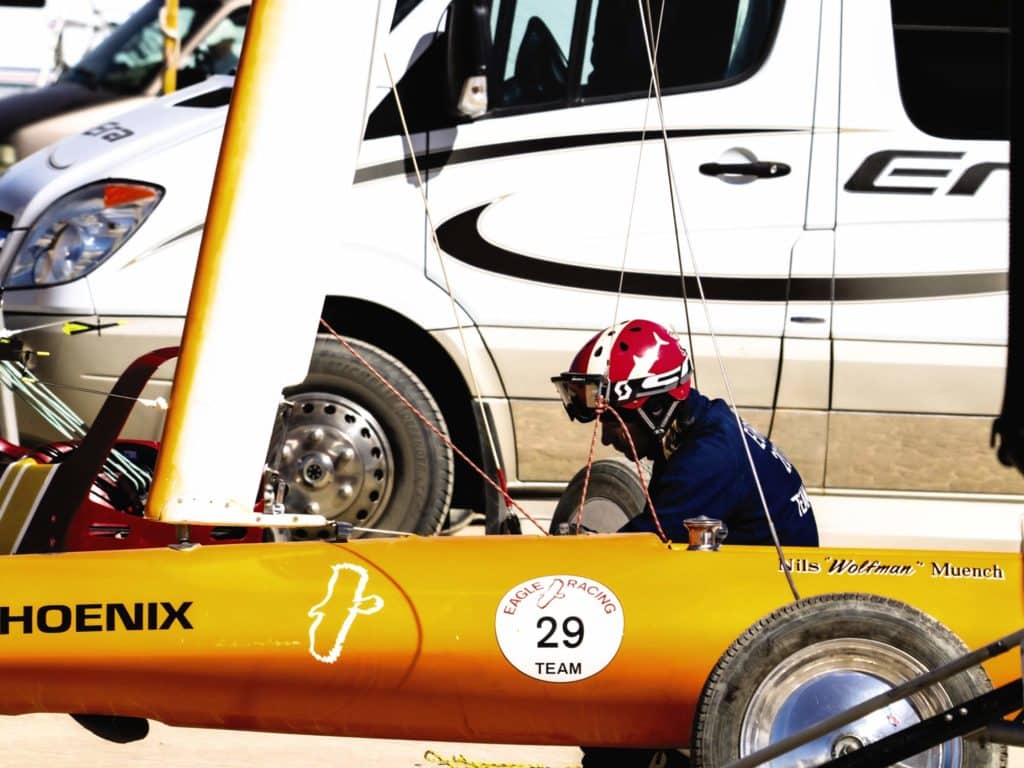

Bassano is part of the S.A.S.S.A.S.S.—Sunny Acres Sailing, Sipping and Soaring Society—which is based in the Black Rock Desert in northern Nevada. There are the Los Angeles Wind Wizards and the Flying Monkeys hailing from central Nevada. There’s an East Coast club, a Midwestern clan, and an entourage from the Pacific Northwest. And at the America’s Landsailing Cup, there are more types than just Manta Twins. Sixty-eight pilots are registered for nearly 90 boats, with sailors from as far away as England and Germany.

The event is split into five starts for 10 separate classes, including the wooden, garage-made Mini Skeeters; 5.6 Minis that look like rideable torpedoes; Manta Twins and WinJammers (single seaters); various NALSA and FISLY class boats that look like larger iceboats on wheels; Sportsmen; and the super-sleek Standarts.

One competitor, Rene Fields, is racing in four different classes: both Manta classes, the FISLY Class 3 and the Standart. She’s looking to defend her title in the Manta TwinJammer fleet, which is the largest one-design fleet in the country. “Hopefully, I get a little break between races,” she says. “If I do well enough, I should have time to run to the bathroom before grabbing the next boat.”

Fields drove her van, “Bubba,” down from Reno, Nevada, where she works as a forensic engineer. At regattas, she sleeps on a wood bunk built into the cabin of her van. A fabric shelf hangs from the back of her passenger seat, storing toiletries, Ziploc bags and spare racing components. Sail bags dangle from the walls, and the rear opens into a mobile workshop.

“Every girl must be adorned with fine jewelry and great tools,” she jokes, swinging open Bubba’s back doors and revealing everything she needs, from spare tires to socket wrenches.

Fields has been a die-hard on the land-sailing circuit since 2014. Like most others, she found the sport through traditional sailing, which she took up on Lake Tahoe after a cancer scare. One of her friends eventually introduced her to the Manta TwinJammer, which, with its bench seat, is a perfect boat to take beginners for a ride.

“We went out at Misfit Flats in Dayton, Nevada. It was blowing over 20, and we were flying along at 50 mph,” Fields tells me. “Eventually, he let me go by myself. Right away, I hiked a wheel and started screaming, and by the time that wheel set down, I was like, ‘I have got to get me one of these.’”

The 2014 Land Sailing World Championship was held in her backyard at Smith Creek in Austin, Nevada. With more than 50 Mantas on the starting line, Fields recalls nothing but “dust mayhem.”

But she was hooked right away and has since become a leading figure on the scene, both socially and competitively. She’s been to Europe several times to race on the beaches, which she describes as “like motocross through a car wash with sand blasters.”

While her fleet has grown to include other land-sailing classes, her true love is the TwinJammer. “To do well in this class, you have to tend the sail at all times,” she says. “It’s the fastest piece of patio furniture on the planet, and the perfect place to start if you want to see what it is all about.”

One easy observation of America’s land-sailing scene, however, is the absence of youth sailors. In Europe, land sailing is a popular high school beach sport, but a quick look around the camp in Ivanpah reveals mostly older men—which makes sense given younger people tend not to have the time and money it takes to disappear to remote corners of the country for weeks at a time. In addition to acquiring a land yacht in the first place, trucks, trailers and tools are also required.

Of course, there’s always an outlier. That’s where 25-year-old Augie Dale comes in. Dale’s grandfather, Bill, has been coming to Ivanpah for more than 40 years. At 82, he’s a land-sailing and iceboating legend, who has won three Knight class national championships and once clocked 120 mph while ice sailing on Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. He now spends his time imparting knowledge to his grandson, which, he admits, is difficult at times.

“You’d think with 42 years of experience, he would listen to what I’m saying,” Bill says of his grandson, “but he doesn’t believe me most of the time. He’s right every once and a while, but very seldom.”

Throughout the week, I watch the two of them butt heads over rig adjustments between races. Young Dale is racing two boats: grandpa’s Knight and a C Skeeter, both of which can race on land or ice. “There’s definitely some tension at times,” Augie says, “but at the end of the day, we’re just stoked to be out on the racecourse together.”

Augie Dale started in ice Optis, where he bagged a North American Championship in 2008. Ten years later, he won the Intercollegiate Sailing Association Team Race Nationals with College of Charleston. In 2019, he won the A Division on his way to a coed national championship, and was runner-up for College Sailor of the Year. He’s now assistant coach at Stanford, but gets to the desert as often as possible.

“There’s a lot less traction on dirt than on ice,” Augie says. “It’s pretty crazy to race against other boats in something that hits 70 mph on the downwind legs and can spin out in an instant. When you look at what the America’s Cup and SailGP have been doing with their wing masts—there’s no way the average sailor can find speed like that without something like land sailing.”

Even the 37th America’s Cup Defender, Emirates Team New Zealand, is getting in on the action. Tapping the team’s designers and engineers, they’re now gunning to break the 126.1 mph wind-powered land speed world record, set on Ivanpah Dry Lake in 2009 by Richard Jenkins’ Greenbird.

The previous two records were set at Ivanpah, but where and when the New Zealanders intend to go for broke is unknown. “Building the boat is the easy part,” Bassano says. “You’ve got to be in the right place at the right time. You could sit out here for three months and never see the conditions you need to break the record.”

Bassano remembers the day the record was last broken. He and Jenkins had prowled dry lakes and salt flats from Nevada to Australia searching for the right conditions, until one day Jenkins happened to bring his boat to Ivanpah because other land sailors had gathered. The forecast was for a completely different speed and direction, but soon the breeze built to 42 knots out of the west, setting up a perfect beam-reach angle. In a matter of seconds, Jenkins captured a dream 10 years in the making.

“The likelihood that [Team New Zealand] are just going to build the boat and break the record next year and move on is very slim,” Bassano says. “Of course, they have more money and computer power than anyone that’s ever tried, but their design is almost an exact copy of Greenbird, which was really radical when it first came out. The Kiwis haven’t gone radical. They’re just trying to improve everything by 5 percent.”

By the time I line up for my next race, I manage to get a cleaner start, yet a windshift leads me to the wrong side of the course, and I find myself in a massive hole. I finish mid fleet once more, and to be honest, I’m not happy about it. I’m no slouch when it comes to water sailing, but none of that means anything out on the playa. Racing in the desert can be frustrating and unpredictable, but it’s always a wild ride. I still have a lot to learn about dirt boats, but rest assured, I’m itching for more Mojave mayhem.