Long before multimillion-dollar Ultime- and IMOCA-class boats began to dominate shorthanded offshore racing, the first transatlantic races were as much about adventure as they were competitive sailing. More than half a century ago, amateur sailors headed off into the wilds of the Atlantic with sextants, plywood and saws for repairs, and, in many instances, the odd case of wine. They sailed to compete, but a higher premium was placed on surviving the race, as opposed to crossings today, with the safety technology now available.

For the French especially, the original spirit of the Transat was incarnated when Eric Tabarly sailed to Newport, Rhode Island, to win the fabled race in 1964, on Pen Duick II, introducing the French public to offshore racing.

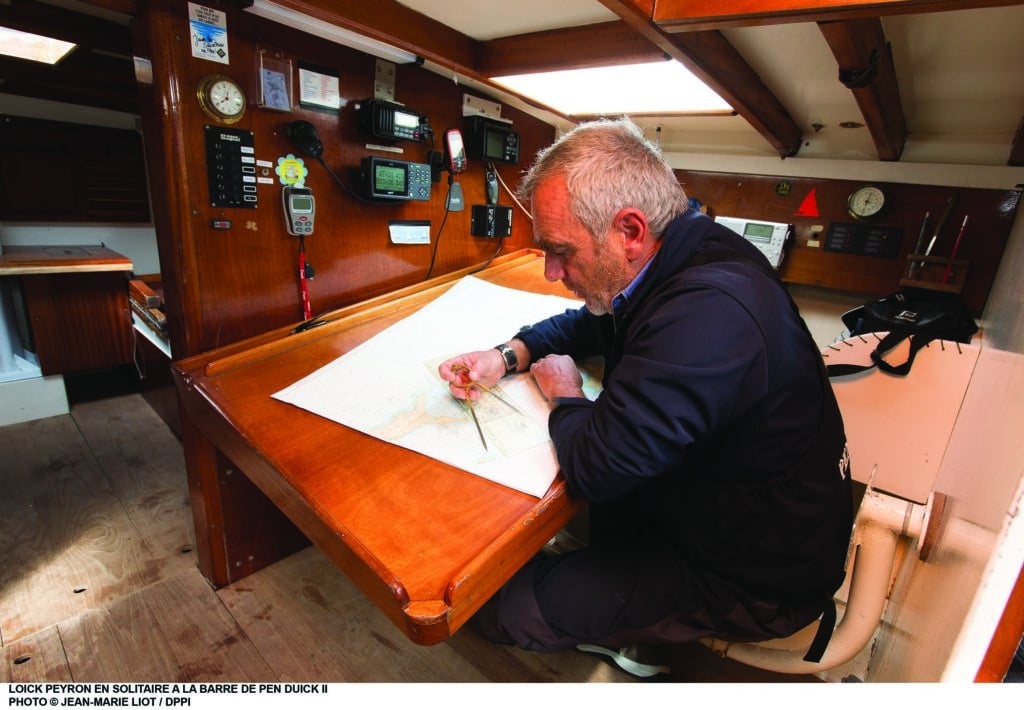

Loick Peyron, who has twice won the Transat, says he is in search of something that has been lost in the race. To this end, he plans to pay tribute both to the origins of offshore racing and to Tabarly, his boyhood hero, by sailing on Pen Duick II (“small black head” in the Celtic language of Brittany).

“I am going to sail in the English Transat exactly like Tabarly did over 50 years ago, with no electronics, no GPS,” says Peyron. “I want to feel the uncertainty, to relive that feeling and the beauty of not knowing where you are, by sailing without GPS.”

Pen Duick II has been restored with new sails and winches. But the vessel is by no means just a pastiched, completely refurbished version of the original. The 13.6-meter double-mast ketch still has its plywood hull and mast. After taking sextant readings on deck, Peyron will sit at the original chart table where Tabarly sat, plotting his course with a chart and compass in the light of an oil lantern.

Without trying to seem falsely modest or brave, Peyron seems more concerned about endangering one of France’s more important cultural artifacts than he is about his personal safety in the worst-case scenario of the boat breaking up on his watch.

“I have to really take care of the boat, so I am not going to take any risks,” says Peyron. “It is part of our French heritage, and I am responsible for it.”

Peyron’s self-professed need to acquaint himself with offshore sailing’s origins also includes plans to sail Happy, a sister ship of Mike Birch’s Olympus, in the upcoming Route du Rhum; Olympus won the race in 1978. Peyron originally planned to cross the Atlantic on the replica boat during the last Route du Rhum, in 2014. But instead he sailed the Ultime trimaran Banque Populaire VII to a first-place finish in that race, after replacing Armel Le Cleac’h, who suffered a hand injury at the last minute.

Peyron attributes much of his success as a skipper to having the opportunity to pilot some of the world’s most technologically advanced boats, including Artemis Racing’s AC72 in San Francisco and Banque Populaire V around the world in 45 days and 14 hours for the Jules Verne Trophy in 2012. But his throwback campaigns on Pen Duick II and Mike Birch’s replica serve as a study in today’s boat technology, he says. “Journalists at the time said the Pen Duick II design was crazy, which journalists still say every time a new type of boat is introduced,” says Peyron.

LOICK PEYRON A BORD DE PEN DUICK II

For example, Pen Duick II is described as the first successful boat geared specifically for Transat races. Its plywood — considered lightweight and sturdy at the time — and wider sail surfaces and size gave the boat speed and stability. It allowed Tabarly to beat upwind against extreme wave conditions in Force 8 or 9 winds while others dismasted, and to maintain speed in light winds during the last 800 miles after Newfoundland.

“I’m very lucky to be able to helm while flying on an America’s Cup boat across the San Francisco Bay at an average speed of 25 knots, but I also feel a need to sail on these classic boats,” Peyron says. “It helps me to think about the sailing of the future.”

Despite the glaring differences in technology and speed on Pen Duick II versus what Peyron is used to, the sensation of sailing remains the same on any sailboat. This holds true whether he’s in the middle of the Atlantic, more than a thousand miles from port, or on a daysail in the Solent.

“The sea is the sea. Whether you are on a 30- or 60-foot boat, the difficulty and sensation are the same on a basic level,” says Bernard Rubinstein, who sailed with Tabarly on Pen Duick VI in the Whitbread Race of 1973, and who is a committee member of the Eric Tabarly Association.

“The technology you use to arrive at your destination is obviously different, and that is what Peyron wants to experience. This is about wanting to return to the origins of the Transat sailing. There is something ritualistic about using the sextant.”

Since Pen Duick II will still have GPS and other electronics on board to meet organizer OC Sport’s race rules, it is easy to assume that Peyron will often be tempted to just push a button to find out where he is, instead of relying on the notoriously difficult-to-use sextant. But given the simplicity of sailing this craft compared to ultra high-tech IMOCA- or Ultime-class boats, Peyron will have plenty of time to finagle with the sextant — or to simply enjoy the adventure. In many ways, his decision to forgo electronics and sail alone will be a spiritual exercise.