“If you have the good fortune to be sailing on a sled, TP52 or faster, you can sail fast enough to stay in the accelerated wind in front of the squall for hours.” —Stan Honey

The Perfect Squall hits at 12 minutes after midnight. This may sound dramatic and dangerous, but squalls—and the resulting downwind rides—are a major attraction of the biennial Transpacific Yacht Race. I have the good fortune to navigate Dr. Philip and Sharon O’Niel’s TP52 Natalie J, a boat fast enough to allow us to hunt squalls, rather than avoid them, which you might do in a slower or doublehanded boat or for safety reasons.

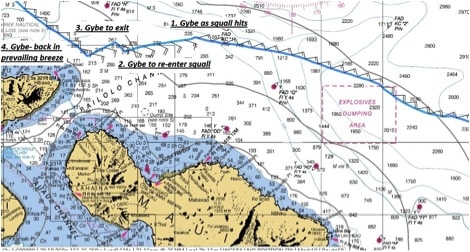

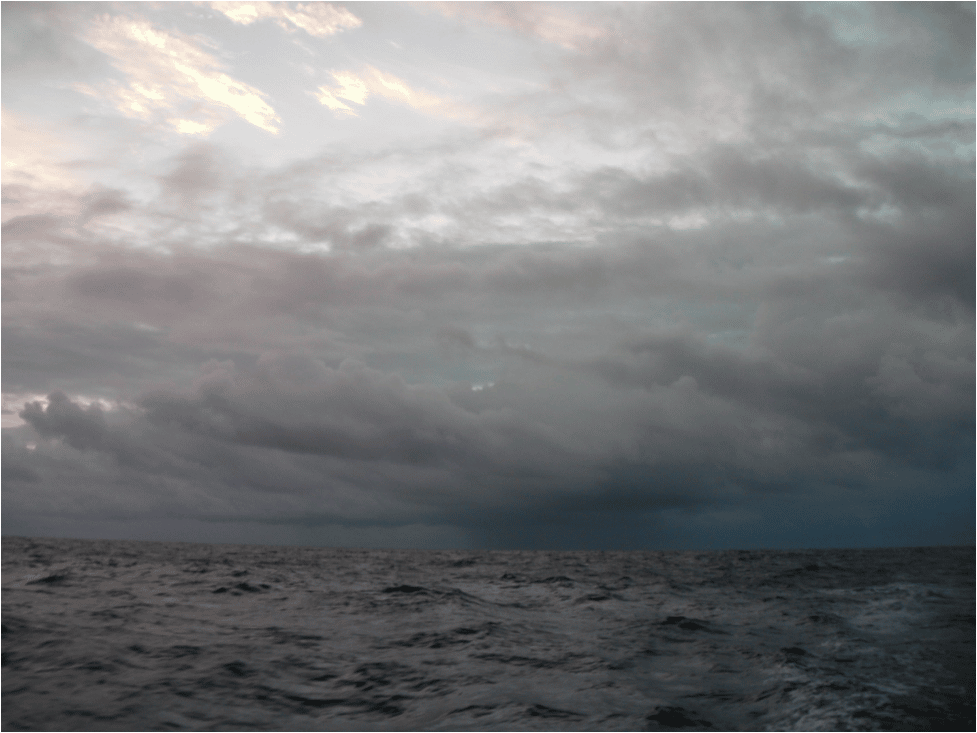

We are 21 miles off the eastern tip of Molokai Island on starboard jibe, and on final approach to the Hawaiian Islands. Our Southern approach is a function of the need to be well to the south of a geographically large cut-off low that reduces the wind on the traditionally favored northern part of the racecourse. The squall appears as we enter the Molokai Channel, a natural wind funnel with a reputation for big wind and big swell, and a place where sailboats become gigantic surfboards hurtling down the waves in white-water, white-knuckle, adrenaline rides.

Throughout the latter part of race, once we entered the squall zone, I had “gone to school on the squalls” as Stan Honey advises in his well-known Transpac primer. The 2013 Transpac is a meteorologically turbulent year. We have lefty squalls (True Wind Direction backs inside of the squall as compared to the gradient breeze), righty squalls (TWD veers or clocks), long squalls, short squalls, non-squalls, scud clouds, misty rain showers, squall-like low clouds, and even cloud lines impersonating squalls. This article concerns only the final squall of our race, and is not intended to be representative of all squalls one might find on a race to Hawaii or any other race.

One of the mental and physical challenges of a Transpac is playing the squalls because of their race-changing impacts: (i) considerable gains are made by the brave few who do so consistently and correctly; (ii) safe results achieved for those that avoid them; or (iii) the penalty of sitting motionless for when you that get a squall wrong.

I first try to identify the clouds, and determine whether they’re useful: do they have increased breeze, and are we sailing an intercepting path? By intercepting, I mean can we catch the clouds or even sideswipe them, without getting caught behind them? Much the same way we might take bearings on competitors, I take multiple bearings over time with the hockey puck (“Puck it” as Chris Williams would say) on a target cloud (or both edges of a large or close cloud) to determine the relative positions and speeds of the cloud and my boat. This is both an art and science as you hone your skills at squall interpretation and engagement; recognizing fully that movement of squalls can be disorienting and deceptive, especially to a sleep-deprived crew.

We also have to realize not all squalls hit during daylight. Quite the opposite, in fact, as they tend to build energy during the heating of the day and release it at night. As a result, much time is spent peering into the darkness trying to interpret more than 50 shades of black or the lack of stars in certain sectors of the sky in order to identify and track squall clouds. Over time, I’ve developed a squall tracking form that helps me with this process and speeds post-race analysis. Fortunately through experience, perseverance, and some science, playing the clouds effectively will become more intuitive with rewarding competitive benefits.

As the perfect squall approaches in the 2013 Transpac, we have prevailing TWD breeze in the high 050s to mid-060s, but we know from an instructive earlier squall we’d likely have a righty. As a result, Bora Gulari, Natalie J’s tactician (a Rolex Yachtsman of the Year and two-time Moth World Champion) and I agree that, if the breeze veers to TWD 075 as the incoming squall approaches, we will jibe on it as it will likely continue to clock further. I step below to add some rain gear because I know it’s going to be wet. From the complete darkness of our TP52’s black carbon cabin, I can’t see the squall (or anything for that matter), but I can feel and hear the system announce its arrival.

The breeze builds instantly, jumping to more than 20 knots. I feel my way in the dark for the cockpit and race up the stairs, re-adjusting my safety gear as I move. I glance at the 20/20 displays, seeing the TWD already at 078. Barely loud enough to be heard above the roar of the wind and rain, Bora is already shouting orders to prepare for the jibe; we are on the same page. As I sprint to the back of the boat I hear the calls, “Bow Ready,” “Trimmers Ready,” “Ready on the main,” and my own voice “Runners ready,” as I grab the runner tail. An instant later, I hear Bora calmly say, “Doc, find a wave and jibe.” Doc O’Neil carves the boat down a wave and we are off on the other jibe. After a couple thousand miles and countless jibes, jibing in 20-plus knots of breeze is no big thing, even with a shorthanded eight-person offshore crew.

The rain intensifies. The boat keeps trucking up and down the swell with boatspeed regularly hitting the mid-20s. The water sounds as if it’s hissing as it rushes under the transom, forming a rooster tail of wake. I wish my friends and family could experience this sensation. Successful teams are night fighters, making up time in such conditions. The Natalie J team feels connected and we know we are making serious tracks with Doc at the helm of his boat. “Slingshot engaged!” The breeze keeps heading and our ground track looks better and better.

The squall’s deluge washes away the pent up frustration that built earlier in the race when sometime during the first night with kite up, we cracked our bowsprit, subsequently discovering it at first light when the pole was observed to be unnaturally bouncing around. This is a big deal on a downwind race of more than 2,000-nautical miles, turning us into the only entrant of the “non-spinnaker pole division.” Even as we had crossed the ridge, we tried a repair, but it failed. Soon after we we’d discovered the crack and alternated between tacking the kite to the bow to using the compromised sprit, which worsened with each mile. Eventually, we’d given up on the bowsprit altogether. Meanwhile, we knew a top race result was slipping away.

But none of that frustration with the sprit matter as we surf wave after wave, propelled by the juiced winds of the squall. The angle of heel under our feet is as good as any of the ghostly red numbers indicated on the B&G displays. Water pours down the deck and washes out the back. Sounds like staccato gunfire erupts each time the kite is eased on the big winch drums, only to be wound back by our big muscle on the handles.

This is a big-money squall for us as the breeze goes all the way around to 105-degrees TWD and we have hit the shift perfectly by jibing onto port pole. Those who hadn’t bothered to jibe are lifted and shot out the side of the squall. Our track on both jibes is virtually a straight line pointing right at the finish line at Diamond Head, with extra breeze—perfect. Given the track of this particular squall, we play the port jibe for 50 magical minutes. As we near the edge of the squall, we jibe back onto starboard to roll into the squall for more fun. Given the relative path of the clouds and the short distance to our destination, we don’t spend much time on starboard pole. It’s obvious in all the darkness that our time playing is nearly over as it barreled along and lost its potency. After 10 minutes, we bounce back to port pole, and head west again to ensure an orderly exit out of the squall. By orderly, I don’t mean ‘safely’, but rather to not get caught behind the squall in the light wind mess that typically trails the squall.

As the clouds scamper away from us, the breeze begins to shift back to where it originally came from and we start to get lifted on port pole. Once we know the squall is past, we jibe back onto starboard pole with a header expected and resumed our track into Molokai Channel with the trade winds propelling us. Our little run-in with perfection, glorious though it was, is now over. No longer are we a rocketship playing a squall in our own little world, we are back to being a boat with a broken bowsprit on final approach to finish one of the world’s greatest ocean races.

Special thanks to Stan Honey, Scott Easom, Bora Gulari, and the owners and crew of the Natalie J.