BeachCat960

Cape Horn has long been the most iconic landmark in the minds of sailors. In fact, for reasons of history, geography, and drama, I think it should be an iconic landmark in the minds of all humanity—so much so that it annoys me when the sailing world diminishes its Greatest Cape by endlessly and tiresomely referring to sailing around the Horn as the “Everest of sailing.” Do you think any climbers would be willing to undermine Everest by calling it the “Cape Horn of climbing”? Cape Horn can stand on its own. We don’t need to compare it to a mountain. It’s an otherworldly place at the bottom of the globe; and its unique blend of soaring rock, harsh seas, and weather astride a key sailing route helped Cape Horn bring ship design and sailing skill to an apex during the 19th-century clipper era.

Bernard Moitessier perfectly captured its essence when he wrote in “The Long Way“:

For the sailor, a great cape is both a very simple and an extremely complicated whole of rocks, currents, breaking seas and huge waves, fair winds and gales, joys and fears, fatigue, dreams, painful hands, empty stomachs, wonderful moments, and suffering at times.

_

A great cape, for us, can’t be expressed in longitude and latitude alone. A great cape has a soul, with very soft, very violent shadows and colours. A soul as smooth as a child’s, as hard as a criminal’s. And that is why we go.

_

And Jack London perfectly captured its challenge, and the degree of sacrifice and commitment it took for a ship and crew to claw past Cape Horn, in his great short story “Make Westing“:

_

The Mary Rogers was strained, the crew was strained, and big Dan Cullen, master, was likewise strained. Perhaps he was strained most of

all, for upon him rested the responsibility of that titanic struggle. He slept most of the time in his clothes, though he rarely slept. He

haunted the deck at night, a great, burly, robust ghost, black with the sunburn of thirty years of sea and hairy as an orang-utan. He, in turn,

was haunted by one thought of action, a sailing direction for the Horn: “Whatever you do, make westing! make westing!” It was an obsession. He

thought of nothing else, except, at times, to blaspheme God for sending such bitter weather.

“Make westing!” He hugged the Horn, and a dozen times lay hove to with the iron Cape bearing east-by-north, or north-north-east, a score of

miles away. And each time the eternal west wind smote him back and he made easting. He fought gale after gale, south to 64°, inside the

antarctic drift-ice, and pledged his immortal soul to the Powers of Darkness for a bit of westing, for a slant to take him around._

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the first small-boat sailors even began to conceive of the possibility of a voyage around Cape Horn. Joshua Slocum stayed inside Cape Horn as the century turned. But in 1923 Conor O’Brien and crew, aboard the 43-foot Saorise, made the passage. Al Hansen, a Norwegian, was the first small-boat sailor to solo Cape Horn, in 1934. Argentinian Vito Dumas followed in 1942, as part of a solo Southern Ocean circumnavigation. And if you haven’t read the Cape Horn travails of Mile and Beryl Smeeton then you have a great read coming. Many other sailors followed in their wakes.

But since those early pioneers, advances in technology (yacht design, search and rescue, satellite positioning, weather forecasting, and communications) have diminished, as technology always does, the sublime challenge and experience of rounding Cape Horn. These days, many sailors relegate the feat to a bucket-list item, to be ticked off if there’s time and opportunity, instead of a voyage deep into the soul, one that places life and death entirely in the hands of the individual, subject to the capricious intent of the monstrous weather systems on the Southern Ocean.

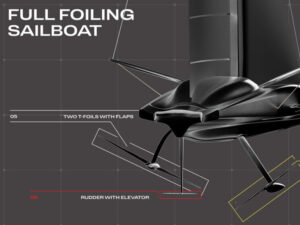

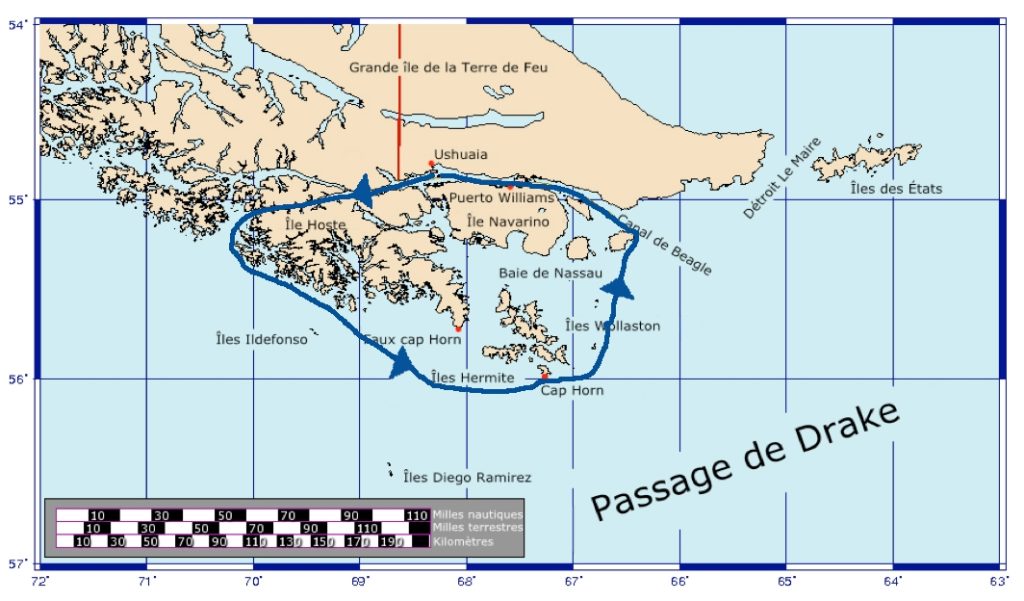

But there’s one way to redeem Cape Horn, to restore it to the mythic status it truly deserves. And that is to sail around it in a small boat that is devoid of all the technology and safety buffers that can strip adventure bare. So I want to thank Yvan Bourgnon and Sebastien Roubine for recently doing just that. They sailed around Cape Horn in a modified Nacra F-20. Yep, a beach cat.

www.yvan-bourgnon.fr

It doesn’t get any more elemental than that. Their 60-hour voyage was everything they expected it might be. Hellish seas, 50-knot winds, a desperate struggle to keep the boat upright and stay with it. “It was the hardest thing I’ve done,” said Bourgnon, who’s sailed everything from the Mini Transat to the Route De Rhum. He added that his Cape Horn rounding required “a dose of insanity.” See for yourself what it was all about.

If you round Cape Horn in a beach cat, you’re reducing the challenge to its most basic—and critical—elements: Sailor, Boat, Southern Ocean, a Great Cape. That’s an adventure well worth having and admiring. Dare I say it’s the equivalent of climbing Everest without oxygen? Either way, putting aside all the modern weapons humanity has developed to conquer and hollow out the greatest natural challenges Nature can offer is exactly the right way to honor the greatest sailing landmark on the planet.