A few days after I raced with Mike Toppa for the first time, I found myself still marveling at his quiet impact on board. Over two light-air days, he’d managed to strengthen and improve an already strong team of a dozen sailors—even though he’d raced on that particular boat only a few times before.

Of course, this is a guy who’s spent the past five decades making a variety of sailboats go faster, so all of us were quite ready to listen. But still I wondered: How does he step into what is basically a new “office” every regatta and instantly improve the team’s performance? Most of our lively conversation during a sit-down focused on superyacht racing because big crews are Toppa’s biggest team-building challenge. But his approach can definitely help improve a team of any size and/or ability. Here’s how he goes about it.

Step 1: Get a ride

“The owners are our customers, and that’s where it all starts,” Toppa says, when we sit down in his office for a chat. Almost 50 years at North Sails confirms the claim that he’s only ever had one job, but Toppa’s responsibilities have definitely evolved. These days, he helps clients make choices about their sails and crew—and then works to optimize both. As he puts it, “There’s always a way to make a boat go faster, so that’s the fun of it.”

He says that most invitations start with a specific regatta, and “that leads to a discussion.” For each option, he unfurls one finger on his left hand: “They might say, ‘We’ll just go and see how we do.’ Or they might ask, ‘Tell me what I need: How many people?’” Most superyachts race with as many as 30 on board, including a full-time crew of six to eight.

A third finger extends.

“If they say, ‘Let’s really try to win this and be as competitive as we can,’ I try to get a read on how much they want to put into it—and how much they want their boat invaded by a bunch of strangers.” Superyachts, he explains, are cruising boats at heart. “These boats travel all over the world. They’ll decide to race, and then they might go cruising for two years, and then race again. It’s really taking a hotel and getting it ready to race against other hotels.”

That’s why he encourages all of his customers to bring friends, even if they’ve never raced before.

Step 2: Meld strangers into a cohesive team

Before a regatta, Toppa researches the crew list. “Every boat’s collective skillset is at a certain level, and then within that group, individual skill levels are different, so I’ll do some homework—who I know, who I don’t know, what their background is—just to get a sense of what to expect.”

Even the captain’s and crew’s abilities might range from novice to expert, and “they’re about to get invaded by 15 sailors who want things done in a certain way, which may not be the way they usually do things. So there has to be a balance there.”

To achieve that balance, Toppa says that he tries to explain the reasons behind doing things differently, “how it affects performance and how it’s a good thing.” That takes time, so “you can’t do it in the middle of a race. You gotta try to anticipate the things that might cause conflict, and try to figure that out. And that, as I said, requires homework to understand who’s there and what their experience is.”

Personalities are another big factor, he continues. “There are a lot of good sailors out there, but too many professional sailors step into every program and act as if they’re on a grand prix boat with grand prix sailors saying, ‘This is how we’re going to do it, and you’re an idiot if you can’t do it that way.’ That just ruins everything,” Toppa says. “But some people just can’t read the room and figure it out.”

When he’s asked to suggest teammates, he says: “I’m always looking at personalities first. Because if you can get people who enjoy what they do and interact with people well, you’re way ahead.”

Step 3: Set achievable goals.

Once he steps aboard, Toppa tries to align expectations with experience by stating one simple goal: to improve as a team. “I’ll tell everybody on the first day of practice: ‘Take the results of every day and how we do things, and put it in the bank; learn and do better the next day. Just every day, incrementally get better and better. And by the end of the regatta, we’re going to be the best team on the water.’”

The surefire way to improve, of course, is practice. Without it, Toppa warns, “especially when you’re bringing people in who are new to the boat, something or somebody is going to break.”

But just like any one-design program, it’s rare to get enough time before a regatta to really gel as a team. “So when there’s a new crew together, I tend to look for the easy things: What are the areas where the gains are biggest? Typically, that’s efficiency. If you can’t tack the boat or get the spinnaker up and down efficiently, you’re just giving away seconds and minutes on the racecourse. No rating is going to make up for that, so getting those basics down is really, really important.”

When the sails do go up, Toppa calls for a bit of time sailing upwind so that he can tweak things. “What I really enjoy is getting on a boat for the first time and making sure that the sails are doing as well as they can, that they’re set up the right way and trimmed the right way, and everybody has an understanding of their range.” His smile widens. “That’s a fun challenge.”

Fun as it is, sail tweaking is only a bit player in Toppa’s overall goal: “Doing as well as we can and everybody having a good time, because that means they’ll come back again. If you turn them off, it’s just not good for anybody.”

The Challenge of Temptation

When Art Santry acquired use of the 2007 J/V 66 that became Temptation-Oakcliff for summer 2024, he asked Toppa to get involved—and it turned into the perfect test of his

team-building skills.

“Art had a group of people from his previous Temptations, and because Oakcliff Sailing owns the boat, there were kids on board too. So it was a real mix of people who hadn’t sailed together before, and hadn’t sailed that boat before. And a revolving door of crew—not just for each regatta, but sometimes each day. It was a challenge to get everybody going off the same playbook.”

Toppa spent a lot of time chatting with each day’s foredeck team, cracking jokes to “get a little bond going, so they’d find it easier to work together when things got hard; little things like that make a difference.” The boat doesn’t have a lot of room for error, he explains. “If you don’t do things a certain way, it’s going to show up fast.”

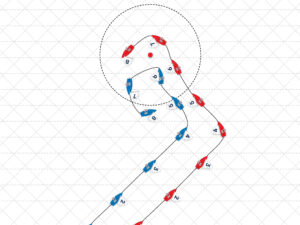

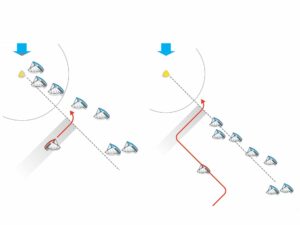

Asked for an example, he describes the cockpit coordination needed for an efficient windy-mark rounding. “As you are approaching the leeward mark, all three pedestals are linked to the pit winch with the spinnaker takedown line. Then you tap out of that and punch into the mainsheet winch to get the main in, and then [as you head up,] your mainsheet guy taps out, and he keeps going on the main while the two forward pedestals trim the jib. It all has to happen sequentially and without any pause, or else you’re going to go around the leeward mark with the spinnaker halfway up or in the water—and the main out.”

“I’m always looking at personalities first. Because if you can get people who enjoy what they do and interact with people well, you’re way ahead.”

— Mike Toppa

Doing things a certain way requires “a sense of awareness, a lot of sailing talent, and a lot of practice. We didn’t have a lot of time on Temptation, so each race was a practice; we learned every day.”

After racing, Toppa again checked in with specific crewmembers to “break down what they do on board and what happened that day.” First, he talked to them individually: “‘What do you think? How can it be improved?’ Then I’d get the other people in that area together and talk it through again collectively, to see how the group can improve. It takes a lot of time.”

And because of that revolving crew door, “the next day, another group of people would come on board. So, every race we were starting maybe half a step ahead instead of a full step ahead. It was always, ‘Let’s see what we can do and make the most of it.’” And even without Toppa on board, Temptation-Oakcliff went on to post a race win at their final regatta of the season, the ORC Worlds.

Only one team hoists the trophy at the end of a regatta, so Toppa chooses a different way to “win.”

“I can’t remember a regatta I’ve walked away from that wasn’t a success,” he tells me, again sporting the wide grin of a guy who really loves the only job he’s ever had. “And what I mean by that is everyone had a great time, and the boat did better than it’s ever done before. To me, that’s a success.”

Two months after my first sail with Toppa, I’m really hoping it was not also my last. His unique, sunny approach—enriched by five decades of taking racing very, very seriously—makes it hard to end our conversation. “I can’t think of many events that went really poorly,” he says. “They probably happen…so maybe I’ve destroyed them from memory. But usually it’s a good experience and everybody enjoys it. And you end up meeting cool people and having new friends; a lot of good things come out of it if it’s done correctly. That’s probably why I’m still doing it—because it works.”