Ed.’s note: A few years ago, I used to run into this guy at the coffee shop up the road from Sailing World HQ. I knew he was in the industry. That he did something with composites. He once hinted he was building a trimaran in his garage. Slow going. As men of few words standing in line waiting for our coffees, we’d nod and head our separate ways. When I finally learned his name, I got that sense I’d heard it before. From something he did, before my time. Another thing before my time was the trimaran Sebago. I know it’s famous, but I’d never knew of Phil Stegall’s adventures with it. Then one day, recently, I open the February 1989 issue and Phil’s story grabbed my attention. I don’t why. Maybe the title, and the little square photo of his cool looking trimaran. So, distracted from what I was doing, I took a seat and read his yarn. It’s a good one. And it’s nice to be able to finally put a face to a name to a story. Enjoy. —D.R.

The start signals were up and the countdown was on. In minutes, 96 lone sailors, including myself, would begin the 1988 Carlsberg Singlehanded TransAtlantic Race. My boat, Sebago, was in the largest class of boats (Class 1); most of the others were French. Total, there were 20 multihulls, all 60 feet long, all sponsored, all professionally campaigned, all going for victory with all the gusto 19 men and one woman could muster. Ahead lay 3000 miles of North Atlantic Ocean. Behind, eight years of dreaming, four years of serious planning and fund-raising, and nearly two solid years of hard work to bring the project to reality. One man, one boat, one ocean … this is what sea stories are made of.

I had literally prayed for a light-air start, and we got it. It’s not my idea of fun to start a race like this in a blow. My nerves are on edge enough. Plus, these boats are lethal in enclosed spaces, especially with just one person aboard. The acceleration is startling, and the turning circle wide. Everyone wants to avoid a collision at this stage. So with only five to six knots of wind and a near weather-end start, Sebago and I were off to an early lead. The calm and balmy day (the one day of summer for England) had brought a large fleet out to watch. My family and friends were on a chartered motor launch, and followed us out to the first mark of the course, Eddystone Rock Lighthouse. Sebago romped away from the competition, slicing the powerboat chop effortlessly.

The wind did not favor us for long, however, lifting us 60 degrees and more. The fleet inside and behind were now inside and ahead. Was this too early to chase? Of course not! I tacked over, took a few transoms, and penetrated the new breeze. We were now a few miles off the Cornwall coast-a coast of stunning beauty if you have time to stop and smell the wild flowers. But right now Sebago and I were back in fourth place. Time to set the reacher and get into top gear.

Sebago instantly came to life. We were skimming across the water at 18 knots, and visibly hauling the leaders back. Distance between you and your competition means nothing in this game.

You can be hull down over the horizon ahead of someone, have to slow up to make a sail change, and in less time than it takes me to tell you, they can blow right by you. But now it was our turn. We streaked by Fleury Michon, Lada Poch, and VSD. And we still had the lead at Land’s End. What a way to start a TransAtlantic Race!

But then things started to go wrong. In a freshening breeze, it was time to roll up the reacher and make a hanked sail change to “Batt Wings Jr.” While I was on the bow making the change, the boat went into irons. These boats can sail backwards faster than some monohulls sail forwards, and in a few short minutes, five boats passed. I spent the next 11 days trying to catch up.

However, this was not yet my low point. By the time we reached the Scilly Isles, I could nearly reach out and touch Poupon, Peyron, and Pean. The wind had almost quit. There was not a sail in sight behind the lead group of five boats. Yet when the sun rose, Sebago and I were alone. The wind shadow of the Scillies had caused a major break in the fleet.

I radioed Bill Biewenga, my shorebase coordinator in Newport. The first Argos report put us in eighth place. What was happening? So meticulous was the planning and the private, coded weather briefing. So light and fast was the boat. But the French were turbocharged, sailing aggressive wind angles, and had opened up a commanding lead in just 24 hours.

By June 7, two and a half days into the race, we had covered 900 miles of ocean, but had slipped to 12th! Worse yet, the foil (lifting hydrofoil) under the starboard float (outboard hull) had broken off. When your boat is a “foiler,” that’s a serious horsepower loss. It’s like trying to race the Indy 500 on three wheels. I called Bill on the SSB; it was four o’clock in the morning for him.

’’We’ve lost the damn foil!” I yelled. “You’ve only got one choice, Steggall,” Bill answered, “and that’s to push on. Somehow, we’ve got to start sailing more aggressive wind angles, and put less emphasis on the waypoints.”

In other words, it was time to graduate from sailing school, and push the hell out of this thing while the leaders were only 80 miles ahead. I could read Bill’s lips, and he was right. Years of hard work, no steady income, and 10 solid months away from my wife Beth and daughter Claire. It all seemed like too big a compromise to be out here and losing.

My plans for this race began in earnest back in November 1985. I had sailed part of the TAG Round Europe Race on the new 60-foot trimaran Apricot with owner Tony Bullimore and designer Nigel Irens. From this positive experience came my first ideas for the ideal CSTAR entry. I had already missed the ’84 race through lack of sponsorship. But I could see why, looking back at the proposals I sent out, and I thought this time would be different.

So, with dreams of corporate dollars, I discussed my ideas with British multihull designer Adrian Thompson. Within a few weeks a set of preliminaries arrived with an accompanying letter to explain the drawings. The letter began, “If you’re in a state of shock after looking at the drawings, here are some design objectives: 1. To design the fastest possible 60-foot race boat with the wind forward of the beam; 2. To produce a power/weight ratio that will achieve the highest VMG; 3. To reduce parasitic drag to the minimum, arid raise lift over drag to new levels; 4. To provide maximum righting moment for a given displacement; 5. To equip the boat with the smallest possible rig to satisfy the above.

It was all pretty heady stuff. The drawings were pinned up on the wall while we went about looking for sponsorship in corporate America. Then, after the normal frustrating period of dealing with closed doors and recalcitrant executives, the drawings went back in the file, and Beth and I began to make plans to sell our Marblehead (Mass.) home and head for Newport (R.I.)—a place where there’s real hustle for anything to do with the marine trade. I began to formulate a plan to build a 45-foot trimaran with money left over from the sale of our house, plus a large bank loan.

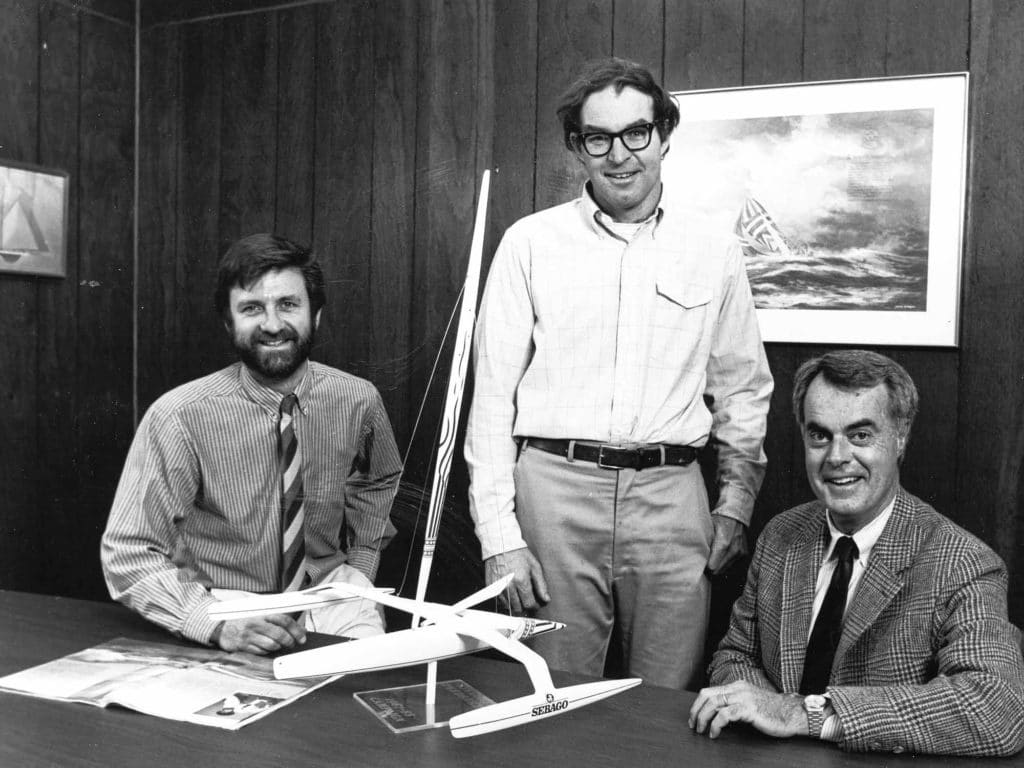

Then, in late November, I received a phone call from an Arkansan named Hampton Roy. My life took a Cinderella turn. Roy agreed to fund the building of the project if, in return, I would help him learn how to sail the boat, which he planned to enter in the 1992 CSTAR. He had read an article about me in a yachting publication—how I wanted to build a craft of sleek and lean proportions and decided to make it possible for me to reach those goals. For my part, I would continue the search for corporate dollars to fund the racing campaign in return for a name and logo for the boat. It was a week before Christmas, 1986. Thompson flew over from the U.K., and the three of us met to study drawings and a model of a very pared-down, foil-assisted ocean racer: 60-feet long, 59-foot beam, and an all-up weight of 6000 pounds!

In the choice of rig, we got ahead of ourselves; the 72-foot-long rotating wing mast of 200 square feet of unreefable sail area was a “catenary ellipse section” — i.e., a mast with a convex trailing edge designed to flatten the mid-section of the main and tighten the leech all in one go as you rotate the spar. The broad and deep mid-section of the mast (four feet fore and aft, 1.5 feet athwartships) meant the weight of the mast could be reduced to ultralight proportions. An all-up weight of 500 pounds!

The rig was light, yet so powerful it proved to be more than a handful on several occasions. During our first sea trial we sailed at better than eight knots to weather and 12 knots running … with just the mast. During one midwinter gale, it took 14 docklines to secure the boat. The vast area of the mast just wanted to keep driving the boat.

Adrian and Hampton left, and we took our daughter to Boston to see the Nutcracker Suite. While the Sugar Plums danced on stage, visions of ultralight 60-foot trimarans danced in my head. It was actually all going to come true after nearly eight years on the sponsor hunt!

We decided to commission Thompson to design and build the boat in Totnes, England, because its advanced complex structure would require constant supervision from engineer Martyn Smith. Smith is a valuable person to have around when you’re demanding miracles from the materials. As chief engineer for British Aerospace, Martyn worked on the development of the supersonic Concorde and the Harrier fighter jet. His specialty is stress and strain, combining high-modulus materials like carbon fiber and epoxy resin to produce a light, rigid, and strong structure. If we were going to beat the French, we had to start with a perfect structure.

We, as the boat was originally christened, was designed to be half the weight of the Irens contingent: Philippe Poupon’s Fleury Michon, Mike Birch’s Fuji Color, and Olivier Moussy’s Laterie Mant St. Michel. Hitachi, skippered by the very experienced Lionel Pean, was at the extreme other end of the power/weight spectrum. His boat weighed almost 14,000 pounds on three largebuoyancy hulls supporting a 90-foot rig. Lionel sailed his power machine from the cockpit in the weather side float. Jean Maurel’s Elf Aquitaine was a similar concept: speed through raw horsepower.

The concepts were so different. Was there a right and a wrong? We had designed Sebago to compete in solo races only, but in France, sponsors expect the boats to compete in many fully crewed races where it’s common to carry a journalist and perhaps even a cameraman onboard. Clearly for them it helped to have a boat capable of carrying a load.

The French built eight new boats for the 1988 CSTAR. For Poupon, this would be his fifth boat in seven years. Mike Birch has had new boats nearly every year since 1976. Moussy, Maurel, Loic and Bruno Peyron, and Florence Arthaud have raced regularly over the last eight or nine years. They cross the Atlantic with frequency. Their dedication and love for the sport is clearly evident in the way they race and prepare their boats. As a community, they live for the next race.

This would be only my second singlehanded TransAtlantic race. In 1980 I raced Jeans Foster, a 37-foot Walter Greene-designed trimaran that I built with the help of many friends. I placed third overall and first in the Gypsy Moth class. Racing Jeans Foster across the North Atlantic was a big adventure, and a completely new and rewarding experience. Never had I enjoyed sailing so much, and learned so much. I had vowed to come back one day to this race with a Class 1 boat, and take a shot at winning.

Although we started construction in January 1987, it took 12,500 hours to complete the boat. We launched December 23, and spent two weeks waiting for suitable weather to begin sea trials. The English Channel in winter roars, but the weather finally lifted enough for some brief trials, during which it could be said our learning curve was almost vertical. It was like being on your first date: not quite sure what to expect, and feeling something in between fear and excitement-skimming across the water, slicing the waves at speeds better than 25 knots.

Although we started construction in January 1987, it took 12,500 hours to complete the boat. We launched December 23, and spent two weeks waiting for suitable weather to begin sea trials. The English Channel in winter roars, but the weather finally lifted enough for some brief trials, during which it could be said our learning curve was almost vertical. It was like being on your first date: not quite sure what to expect, and feeling something in between fear and excitement-skimming across the water, slicing the waves at speeds better than 25 knots.

The acceleration in each puff was enough to race your heart and grab at your stomach.

Two sports marketing professionals, Rick Munson and Patrick Leahy, had been working for seven months to secure sponsorship without success. You would think if you were in possession of a sexy $600,000 super yacht, all ready to race, that you would be turning sponsors down. Rick and Patrick had presented our marketing and public relations plan to more than 40 companies. We were in an 11th-hour situation. Then long-time friend and sailing guru Walter Greene suggested I call Sebago (makers of Docksides boating shoes and other classics).

Sebago had sponsored both Walter and his wife Joan over the years and were very familiar with offshore racing multihulls. Vice President Dan Wellehan races a yacht himself, and so is fully involved with the sport. After some friendly discussion, Sebago made the decision to sponsor the boat for two major races: the CSTAR and the Quebec-St. Malo. Without Hampton Roy, the project never would have been possible. Now with the support of Sebago, our team was complete and our campaign on track. We were ready to go to La Trinite and Brest in Britanny, France, for two key warm-up regattas.

The racing proved invaluable. We witnessed just how hard the French were willing to drive their boats. Sebago sailed upwind higher and faster than most, but we had lost a foil during our delivery from England to France, so we were particularly weak in fresher conditions.

Back in Plymouth I established a routine of running several miles in the morning, and then sitting down with our team, Bill Biewenga and Joan Greene. Both Bill and Joan have had extensive sailing experience: Bill has sailed two Whitbreads and Joan has traversed the North Atlantic many times over the last eight years and built several multihulls with her husband Walter.

Joan and Bill would fight to keep the job list down to a dull roar, while I added to the list—wheel steering inside the canopy, for example. Sailing one of these boats at over 15 knots is similar to standing in front of a fire hose. On deck, there is simply no way to get away from the constant spray. Your eyes sting, and no matter how good the foul weather gear is, the water finds a way in. To be cold and wet greatly reduces your efficiency, so the new steering position seemed worth the effort.

Actually, the boat is usually steered by autopilot. We had already built a rigid canopy above the companionway, extending several feet over the cockpit, giving me a place to hang out and keep an eye on things. The canopy also housed the Autohelm autopilot, Loran and other instruments, and provided me with shelter enough to sleep on deck through most of the race.

The week before the race started, many friends from the States joined us, including Wayne Calahan, Liz Franks, Claudia Geary, Hampton Roy, my parents from New Zealand, and Sebago’s Diane O’Neill and Eric Mallet. My saiing friend and companion on several TransAtlantics, Walter Greene, joined us before the race, and took care of many of the important technical jobs still left. Bill left for Newport a few days before the start to set up our shoreside support, and to begin a liason with Bob Rice, our weather expert from Weather Services, Inc., of Massachusetts. Together, Bob and Bill played a vital role in helping me guide Sebago across the ocean, avoiding the weather hazards and, from a tactical sense, making the best use of the winds and currents.

The third day of the race produced a turning point. There was no question I was driving the boat harder than I’d ever driven it with crew. The wind angle seemed to suit us as we tore off down the rhumbline. The next Argos fix showed we had climbed from 12th to 7th. The boat proved she had what it takes to sail in world-class competition, and, despite the missing foil, we began to take boats and pull back the leaders. It felt as though I was finally in tune with the weather and the boat. Another day passed, and we pulled back three more boats to take fourth. The hard work was paying off.

I spent 24 hours straight on deck trying to deal with a constantly changing breeze-light and variable. Sebago’s light displacement meant acceleration was instantaneous, but so was stopping. It was necessary to be on hand to fine-tune my course and sail trim almost around the clock.

During my twice-daily check with Bill, I could sense the relief in his voice. We weren’t there yet, but the moderate conditions were perfect for our kind of boat. It was not unusual to see 15 knots of boatspeed in seven knots of true wind. If only I could manage more sleep. I often heard voices and several times awoke to think I was on someone else’s boat. The sensation would only last a few seconds, but it was enough to concern me that I might get up and walk off the boat. For this reason, I always slept with my safety harness on. My other big concern was oversleeping. During the 1980 race I had slept through several alarm calls, so for this race we had connected a house fire-alarm and a two-hour timer. I rarely slept for more than 20 minutes at a time.

While Poupon, Moussy, and Peyron were all to the north just off the coast of Newfoundland, we chose a southerly course just south of the Grand Banks. We sailed to a waypoint several hundred miles out from Nantucket, but on the same latitude. Halvard Mabire, Florence Arthaud, and Bruno Peyron were all behind me and to the south. As much as I wanted to beat the three ahead of me, I had to cover, since going for broke to win might cost me fourth place on the tricky approach to the finish.

As the race closed in on Nantucket, Poupon was 200 miles ahead of me and therefore out of reach. How did he get a full day ahead of the fleet? He certainly gave us a sailing lesson, especially toward the end of the race. He places great emphasis on shoreside communication, and has an expert weather and tactical adviser, Jean Yves Bernot, working full-time to optimize the route. Through ship to shore telex, Philou communicated every change in the weather, sometimes 18 times a day! He was literally Jean Yves’ eyes and ears, and it showed in the later stages of the race. Poupon’s course had been unusually far north for a modern TransAt. He had to tack to clear Cape Race while I was more than 100 miles south. He even sailed inside Sable Island off Nova Scotia! His route worked so well because the wind never switched to the southwest as we all expected. It was as if the rest of us overstood the mark while he sailed one closehauled, perfectly executed tack to the finish. However, through working hard, I had come up to within a mere six miles of Lada Poch, and was only 20 miles behind Moussy on Laiterie Mont St. Michel. We were on the wind in around 10 to 12 knots of breeze, unfortunately on port without the foil.

The problem was we weren’t quite laying Nantucket—the final turning mark of the course. The weather forecast called for the wind to go southwest. I was now farther north than my two closest rivals, so if the wind should head us, I might possibly cross ahead of them before Nantucket. I was very much on edge. For seven days we had raced head to head, always taking miles out of the leaders, and a simple windshift would now secure second place for Sebago. I constantly trimmed sails and fine-tuned the Autohelm. I threw all the food and water overboard to squeeze every ounce of speed from the boat. The closer we got to George’s Bank, the more the wind oscillated. I called Bill for the third time that morning, and we decided to try a tack south. It was discouraging, heading east of south. I decided to tack back and at least be heading west. We were only 15 degrees from laying Nantucket, but all the time making ground toward the turbulent waters of George’s Bank.

The wind never headed us, and so, on the last night out, we found ourselves smack on top of George’s Bank, in a tough spot. Confused seas and freshening breeze made it impossible for the Autohelm to control the boat. So, I hand steered throughout the night, which included one very near miss with a large fishing trawler, and, for a short period of time, a complete blackout of all electronics as the pounding had shaken loose one of the main battery connections. There were literally so many fishing boats around me that it was impossible to go below or leave the cockpit for any reason. Despite the freshening breeze, I kept full sail on to power through the confused seas, and to get off George’s Bank and away from the fishing fleet. The thought of finishing, and being home after so many months away was motivation enough to push the boat on, regardless of the fact that I had been up for 48 hours and had not had a chance to cook or eat a decent meal in several days.

I hand steered throughout the night, which included one very near miss with a large fishing trawler, and, for a short period of time, a complete blackout of all electronics as the pounding had shaken loose one of the main battery connections. There were literally so many fishing boats around me that it was impossible to go below or leave the cockpit for any reason.

As we screamed around the corner of Nantucket and headed for No Man’s Land with only 28 miles to go, I disconnected the autopilot, and at the same time thanked it for steering the boat almost continuously over the last 3,000 miles of ocean. It’s unusual to find a piece of electronics, especially one as undersized as the Autohelm 2000 and as immersed in water as it was at times, that provides complete reliability and for such an important task.

The sail to the finish in a hazy but brisk sou’wester was like a magic carpet ride. The boat was wound up and flying. Off Brenton Tower I was greeted by friends and family. Sebago and I had placed fourth. For some reason, I was surprised. I had imagined that in the past 24 hours of sailing on George’s Bank and the slow going up to Nantucket, I had surely dropped a couple of places.

I’ve never worked so hard in any sailboat race to finish fourth, and felt so pleased with the result. Poupon, Moussy, and Peyron are the true professionals of the sport. I felt I was in company with the best in the world, and, despite the broken foils and only 15 hours sleep in 11 days, I had to say it was one of the more positive experiences of my sailing career.

Sebago is a very responsive and easy boat to sail, and at times is probably too sensitive to changes in wind speed and wind direction. It demanded nearly all my attention to sailtrim and course, which meant I spent almost no time below except to briefly navigate, talk on the radio, or cook the occasional meal. In 11 days, Sebago blazed her way across the ocean to set a new American record (she was the only non-French boat in the first eight finishers) to the delight of her owner, designer/builder, sponsor … and her skipper.•

Original footnote: The Carlsberg Singlehanded TransAtlantic Race occurred in June 1988. In August, sailing with a full crew, Phil Steggall had to abandon Sebago during a gale in the Quebec-St. Malo Race. Though badly damaged, Sebago has been salvaged, and Steggall plans to refit her to race again.