There are so many things that can go wrong over the nearly 30,000 miles of the Vendée Globe: routing and tactical errors, boat breakages, collisions, sheer bad luck—you name it. And that’s why Frenchman Charlie Dalin’s victory in the 2024-25 edition is indeed so rare. Four years ago, Dalin was first across the finish line but was relegated to second place on corrected time when runner-up Yannick Bestaven, of France, was awarded a time bonus for helping in the rescue of a rival and declared the winner.

It was fair enough, but the result left a feeling of unfinished business for Dalin, a modest and self-effacing character from the French port city of Le Havre. But Dalin didn’t let it get the better of him. Instead, together with his team, he set about trying to do the impossible by removing the asterisk in the historical record next to his name and winning the race outright.

The 40-year-old father of two at the helm of Macif Santé Prévoyance, the latest foiling design from the board of Guillaume Verdier, sailed an almost immaculate race, hard-driving and relentless in his pursuit of optimal performance. Dalin built his victory on a punishingly fast leg across the South Atlantic, when he took a direct route from Brazil to South Africa ahead of a perfectly timed depression. Then he took a courageous chance in the southern Indian Ocean to go deep in front of a monster storm system, jibing along the racecourse’s ice limits—a calculated strategy that all but one of his nearest rivals chose to avoid.

But this is not to say that it was a walk-over. Far from it. Dalin was pursued all the way round the world by two of his countrymen, Yoann Richomme on Paprec Arkéa, who led at various times, and Sébastien Simon on Groupe Dubreuil, who was hampered in the second half of the race by a broken starboard foil. They duly took second and third on the podium. Richomme finished 23 hours behind Dalin and Simon 2 days, 17 hours behind on the very same boat that Charlie Enright and his teammates raced to victory in The Ocean Race 2023, under the colors of 11th Hour Racing.

Dalin crossed the finish line off the French Biscay port of Les Sables d’Olonne after 64 days, 19 hours, 22 minutes at sea. The numbers here are breathtaking: He broke the previous race record, set by Armel Le Cleac’h, of France, in the 2016-17 edition, by 9 days, 9 hours, 12 minutes after sailing 27,667 nautical miles at an average speed of 17.79 knots. And this was in a monohull, and it wasn’t all reaching and downwind speed sailing.

To put this in context, consider that Dalin was at sea only half a day longer than Bruno Peyron and his crew on the 109-foot maxi-cat Orange when winning the Jules Verne Trophy for the fully crewed round-the-world record in 2002. (That record now stands at 40 days, 23 hours.) On the one hand, this was race-winning form from Dalin, but it also meant a rough and noisy ride for the skipper, even on a flying boat that nosedives in big seas less often than some of its older rivals.

“I don’t think I’ve ever experienced emotions like these before,” Dalin said at Les Sables D’Olonne, after being given a hero’s welcome by a crowd who poured into the finish port for his arrival in mid-January. He was almost overwhelmed by what he had achieved. “This is by far the best finish line I’ve ever crossed. Today, I can confidently say, I’m the happiest man in the world,” he said. “We’ve worked tirelessly over the past four years to make this dream a reality. The boat was incredible, and everything we’ve lived and worked for came together in this moment,” he added.

Richomme, who made a storming start to his IMOCA career with two solo transatlantic race wins in the buildup to this Vendée Globe, was happy to pay generous tribute to a superior competitor at the finish. “I came up against someone stronger than me; Charlie was simply unbeatable,” said the 41-year-old whose foiler is from the boards of Antoine Koch and Finot-Conq. “He’s been stratospheric in IMOCA for several seasons, and it’s hard to challenge him. I’m thrilled for him to have a bit of redemption from the past.”

Dalin, meanwhile, credited Richomme for pushing him to a level of performance that he would not have reached on his own. Reflecting on his circumnavigation, he said that making the right weather call north of Cape Frio on the Brazilian coast was a key moment. Then he enjoyed what he called “exceptional conditions” in the Southern Ocean and, in the final stages, he had a boat in good shape for a full-on race up the Atlantic. Along the way, Dalin dealt with a series of technical issues with ease, among them sail repairs and keel and pilot ram failures.

Simon Fisher, formerly the navigator with 11th Hour Racing who advised Dalin on his meteo strategy before the start, said that the French skipper had shown all his experience, knowing when to push and when to hold off and preserve his boat. “Charlie sailed very smart,” Fisher said. “He’s obviously a very talented sailor and, being a naval architect, is very dialed in to his boat. For me, his success in this race was a combination of good tactics and strategy, and good boatspeed, and using those two things when he needed to. You can easily run yourself into a big rut in these races and push too hard, but Charlie did a great job of knowing when to put the hammer down and build a lead, and when to be a little more conservative.”

Dalin’s race against Richomme and Simon apart, there was an excellent fight for the minor places in the top 10 when, a week later, Jérémie Beyou, of France, in fourth place, was the first of six boats home in just 37 hours. These skippers battled brutal weather as they returned to northern Europe in classic big-winter conditions. Among them was Justine Mettraux, of Switzerland, in eighth place, who became the first female and first non-French sailor to finish.

Beyou, on Charal, had started as one of the favorites with his much-tweaked Sam Manuard design. But his fifth Vendée Globe did not go as well as he may have wished; he struggled to match the leading three for pace. He found the wild weather in the closing stages stressful, and at the finish, he underlined that even minor places in the Vendée Globe are now more valuable than ever.

“There are fourth places that feel like defeats, but this one feels more like a victory,” said the 48-year-old skipper originally from the Breton town of Morlaix. “It took me a bit of time to accept that it would only be fourth place, but in the end, I’m proud.”

This recent edition of the race was record-setting in many ways. It saw a new solo monohull 24-hour distance record—an incredible 615.33 nautical miles—set by Simon heading south in the Atlantic. It included the youngest competitor ever to finish the race in the form of the 23-year-old sensation Violette Dorange, of France, on DeVenir. It featured Jingkun Xu, the first Chinese sailor to complete the race, a remarkable individual who lost his left arm up to his forearm in an accident as a child. He completed the course in 30th position on board Singchain Team Haikou.

And it also featured the race’s biggest fleet, with 40 boats taking the start in early November—seven more entries than the previous record in 2020-21. More importantly, it saw the highest number of finishers, with only seven of the 40 starters failing to make it round under the rules. Among them was 2020-21 winner Yannick Bestaven, who was forced to stop in southern Argentina to repair his steering system on Maître Coq V.

The number of sailors who were forced to abandon the race translates to a failure rate of only 17.5 percent. This compares with a high of 62 percent in the 2008-09 race, when 18 of the 29 starters dropped out, and reflects the increasing professionalism of the teams and the way they prepare boats for what is the ultimate offshore-sailing test of human and design. It is also the consequence of the demanding qualification process for the Vendée Globe now in place and the busy calendar of IMOCA races that lead up to the race through every four-year cycle.

Whereas in the past the Vendée Globe has seen tragedies when sailors have been lost, or dramatic rescues carried out, this race was notable for the absence of such events, arguably a sign that as a sporting event, it is maturing. Antoine Mermod, president of the IMOCA class, considered the completion rate a big step forward in terms of the race’s sporting credentials. “It’s very important that the skippers can complete the race, and can compete at a sporting level, and that the Vendée Globe is not a race of elimination because of technical issues,” he said.

This race featured six female sailors, proportionately slightly less than the 2020-21 edition, when six women also took the start in a fleet of 33 boats. Mettraux and Dorange apart, the female entrants included Clarisse Crémer, of France, who finished her second Vendée Globe in 11th place on board L’Occitane En Provence—the boat sailed by Dalin in the 2020 race, then named Apivia. Veteran solo campaigner Sam Davies of Great Britain had a disappointing race, finishing in 13th place on Initiatives-Coeurs 4, in what was her fourth and likely final Vendée Globe. And her fellow Brit, Pip Hare, sponsored by the California-based customer and employee experience management company Medallia, saw her second Vendée Globe abruptly end with a dismasting south of Australia.

With ever-improving communications with boats even in the remotest locations, the flow of information and insight from skippers was better than ever. Race fans were treated to a steady stream of onboard video updates, photographs, audio recordings, and postings on a variety of social media channels. The race places the skippers front and center in their own soap opera, whether they like it or not. It all means that there has never been a better time to follow their adventures from the comfort of an armchair.

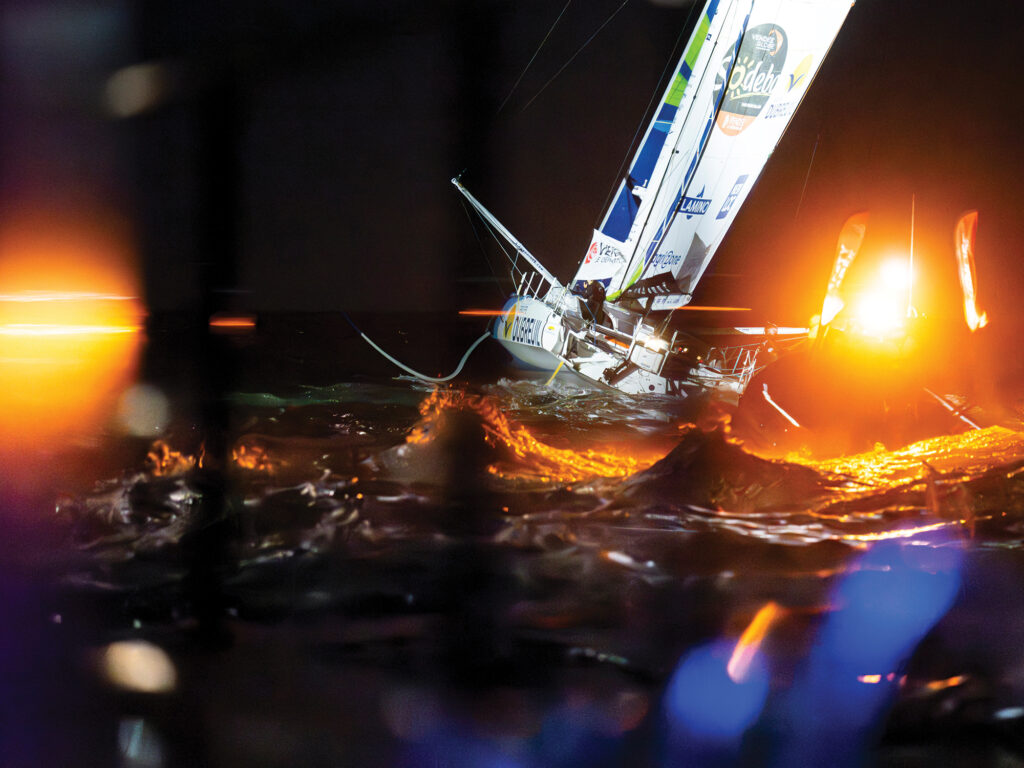

It also means that the reporting is getting better and the impact more dramatic. The race featured countless gripping pieces of film, not in the least a memorable sequence by French sailor Tanguy Le Turquais on the daggerboard-configured Lazare. Early in his Southern Ocean passage, Le Turquais broke several battens in his mainsail during an uncontrolled jibe and filmed himself in a state of utter despair, cursing his incompetence and furious that he had placed his race at risk. Then we saw the high that followed as Le Turquais celebrated, ecstatic that he had managed to effect repairs and get his race back on track. He went on to finish 17th, second in the daggerboard division by just 16 minutes, behind Benjamin Ferré on Monnoyeur-Duo For A Job.

Much later in the race, Beyou sent an equally memorable video capture. This was the Charal skipper only a few days before the finish, sailing in 40 knots of wind in the North Atlantic, wincing at every crash, and looking physically and mentally exhausted by the challenge of trying to complete the race and keep his foiler in one piece. His haunted appearance showed us better than any number of words or interviews could do just how demanding this real-life drama remains and how true these amazing characters are to sailing’s most fascinating race.