As a few challengers and the defender train on Bermuda’s Great Sound with their foiling test platforms, the checklists are long and technical, but there remains a focus on a match race’s most essential skill: winning the start. All the data in the world can’t control when and how quickly six men collectively pull the trigger. It’s something they must drill into their muscle memory until they get it right: get on the foil at full speed, and break away for Mark 1.

“Prestarts will be very exciting in the next Cup,” says SoftBank Team Japan’s Chris Draper. “The boats will be much closer in speed, so there will be more passing and more maneuvers, [and] crew work will be important. They’re highly maneuverable boats and exceptionally fast downwind, but the starts, as always, will be critical.”

How does an America’s Cup team perfect such a fundamental part of the race? We probed Draper further.

“One thing Oracle and Emirates Team New Zealand developed really well in the last Cup was a box that basically helps in their prestart maneuvering,” Draper says. “In the monohull days, you had guys who could look at the box, extrapolate the data, and quite easily determine how long they have to get to the line and how much they have to burn. The boat would hit the line exactly on time. It’s so much harder in these boats (AC45 Turbos) because you have so many other variables. If you don’t make the foiling jibe, your time to the line changes dramatically.

“With Luna Rossa (Italian challenger in the AC35), we didn’t have time to develop a starting package, so we were just using human input and our eyes. At 40 knots, if you’re one second off, it’s a huge difference. Now, in Bermuda, we’re building up our data, we have a nice starting package, and we’re getting to use it, but then we start adding in other things. If it’s 10 knots [of wind], it takes us longer to get onto our foils, for example, but if it’s 18 knots, we can pop up effortlessly and be at target speed very quickly. If you’re not foiling, the other guy is going three times faster.”

What are the most effective drills?

There’s no substitute for doing starting drills against other boats and teams. When you’re slow in the prestart, you’re a duck, so we know we can never be too good at the boathandling. If our boathandling is good, we can keep it ripping the whole time, making it easier to attack and making it harder for the other boat to defend. We have to be able to put the boat where we want and not be dictated by someone else. In the confined race area in Bermuda, boathandling will be key. That’s what this next Cup will be about: There will be a lot of maneuvering, and that affects your handling.

You have sophisticated software, but at what point do you start on instincts alone?

We have to develop both at the same time. There are times when the box says one thing, but you’re looking up the course and seeing significant pressure or a shift approaching. So the box is a reference, and then we have to look at what the box can’t see and put the two together. A lot of it comes down to repetition and using the box as a seventh, extra team member.

Speaking of team members, you have six, and they’re all busy in the prestart; explain the roles of each during the final approach.

We’ve got position No. 1 at the front and position No. 6 at the back. No. 1 and 2, their priority all the time is to produce hydraulic pressure for all the functions around the boat: daggerboard controls, wing twist and jibsheets, for example. The guys in the back have the wing and the wing sheet. Then you have wing trimmer and helm. We divide it up so No. 2 is helping with time to the line and jib functions and processing some info that’s coming from the box. No. 3 is doing the timing. No. 4 is giving feedback about the other boat and focusing on the wing. Then No. 5, myself, helps keep the boat going as fast as possible relative to laylines to the starting line. I assist with time and distance and how much time we have to burn while No. 2 is talking about how long to the line.

Dean [Barker] is driving the boat and determining where he wants to go, what the next maneuver is going to be, and how he wants to exit the maneuver. One thing that’s tricky is that someone else is driving [while the helm crosses the boat to the other wheel], so if Dean doesn’t tell me where he wants to go as we exit the maneuver, I can potentially put the boat in a position he doesn’t want to be in. On a monohull, the helm always has control of his destiny, but not in these boats.

There’s a lot going on there, even before you add another boat going after you. How easy is it for one small mistake to make it all end badly?

There’s a massive sequence of functions that have to happen with every single maneuver. When you’re sailing these boats, you’re always within a button press of something going bad, so if one or two buttons get pressed — or don’t get pressed — then the maneuver will get compromised quickly. Getting it right is about building muscle memory in those functions and communicating what’s next. There are only six individuals, and they have loads of things to do, and they need to do them efficiently every time.

Then you add foiling into the equation. How do you keep up with the adjustments?

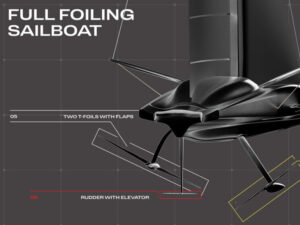

The more unstable you are while foiling, the faster you go, so the better your control systems and operators are at using the systems, the faster the foils you can have. Dean is constantly adjusting the foils. When it’s puffy or a little bit choppy, for example, you have to adjust the rake often. The more maneuvers you do, the more you have to adjust the rake, and the more adjustments you make, the more oil you need, which means you need more grinding. There’s no way to dumb down or automate the systems because it’s three-dimensional sailing now.

Does the adage “Never get slow in the prestart” apply to foiling AC45s as well?

One of the things we’re seeing in the prestart is the importance of how quickly you can pop up on the foil and how quickly you can stop. If you’re foiling at 40 knots, it’s a lot harder to stop the boat than if you’re displacing at 20 knots. With these boats, compared to the AC72s of the last Cup, we can sail at much higher angles on the foil, so that changes things. The techniques to stop the boat will be more important than before, as will techniques to climb as high as possible and not get hooked. It’s going to be a lot easier to get hooked in the new boats than it was in the 72s.

What’s the ideal final approach in terms of time and distance with the AC45 Turbos?

It’s difficult to say. It depends on the angle you’re sailing and the angle to Mark 1. It might take about 15 seconds to be up, ripping and settled, and the farther you get from the line, the harder it is to judge the time. The windier it gets, the faster you go, so it’s always a case of finding the balance. Prestarts will be very exciting in the next Cup. The boats will be much closer in speed, there will be more passing opportunities, and the crew work will be critical. They’re highly maneuverable boats and exceptionally fast downwind, so it will be very cool, from start to finish.