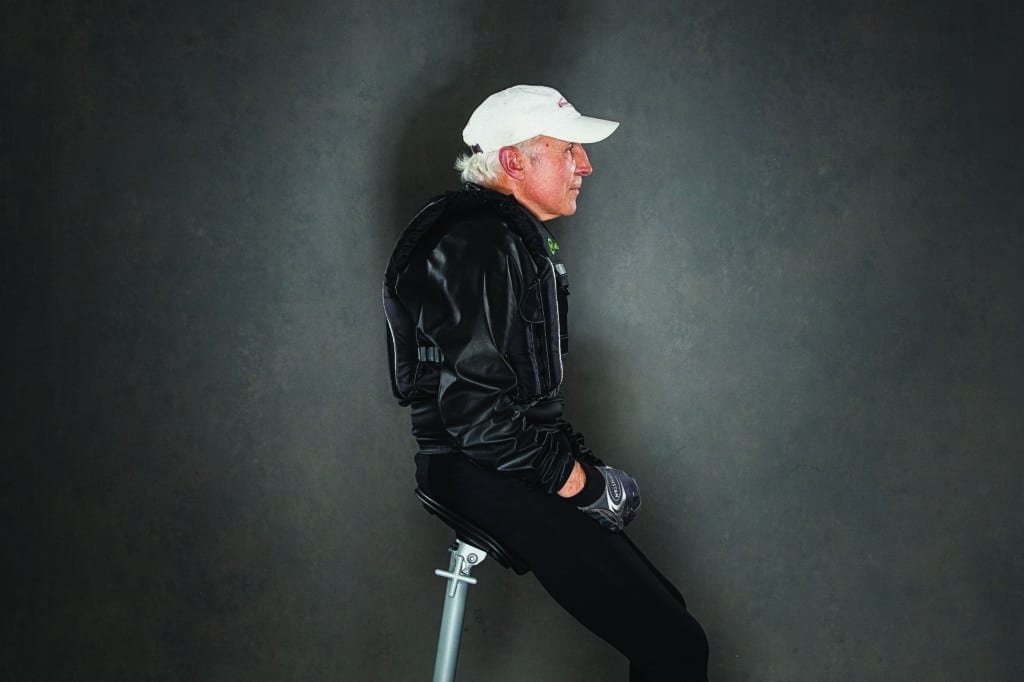

Peter Seidenberg stands aside his meticulously kept Laser. Tufts of white hair, the only obvious hint of his 78 years of age, spill from his ball cap. He’s dressed in tight neoprene hiking shorts, smiling, chatting with a competitor. At Laser Radial regattas, he routinely rigs up alongside competitors young enough to be his grandchildren. On land, these nippers refer to him as Mr. Seidenberg, but on the water, the generational divide is nonexistent. In 2016, Seidenberg made his 32nd appearance at a Laser Masters World Championship regatta, a feat unto itself — but 12 victories? That’s unheard of in any one-design class, which is why his peers in the Laser class call him the Iron Master of Laser sailing.

It’s unusual for a sailor to be so devoted to a single class, but it’s the purity of competition in the Laser that makes him a permanent fixture, regatta after regatta, year after year, decade after decade. He says he enjoys the one-on-one competition the Laser provides. “It’s a simple boat because there are restrictions on what you can do to it,” he says, “but it’s complex in that little adjustments make a big difference.”

He participates in club-level regattas on lakes near his home and casually spars with whoever shows up on Tuesday nights in the summer on Rhode Island’s Bristol Harbor, but he has also stamped his passport countless times in the pursuit of international competition and training. On the water, he is as cool as Steve McQueen, never yelling or scolding. His sailing and his results do the talking.

Once, at a regatta in Maine, a competitor felt Seidenberg wasn’t entitled to room at a leeward mark rounding, but Seidenberg felt otherwise. The competitor launched a tirade. Seidenberg didn’t utter a word. He contemplated the situation, realized the onus was on him, and simply withdrew from the race.

“I was not going to let him ruin my day,” says Seidenberg. As karma would have it, he then won the next race.

At another regatta, after a rare midfleet finish, he reached into the water, ran his hand along the leading edge of his rudder, and then held up a large clump of seaweed. Turning to a fellow middle-of-the-fleet competitor, he quipped: “This is my excuse. What is yours?”

Seidenberg sails in dozens of events every year and abstains from drinking alcohol during competition. For training, he goes to the gym, rides his bicycle regularly, and studies yoga. In the winter, he travels to warm locations to train, such as Cabarete, in the Dominican Republic, and attends warm-water events.

The Laser’s simplicity and world-class competition, he says, are what keep him devoted to sailing a boat the devotees refer to as an “ironing board.” With a smile, he says: “It’s not that I have delusions of glory of being an Olympian. I like that it gives me an incentive to work on my fitness. Without the Laser, I would not work out as effectively. I love sailing and look forward to meeting my friends at the various regattas.”

Seidenberg was born in 1937, in a small village in East Prussia near the Lithuanian border that is now a Russian enclave. When he was 4 years old, his father was drafted into the military and went missing in action on the Eastern Front during World War II, leaving him, his mother and his younger brother to fend for themselves in the family’s bomb shelter.

“When the air sirens were blaring, that meant we had to get up and get dressed and go down in the basement, hopefully to survive,” he says. “It was certainly much harder on my mother than me. In the morning, on the way to school, we collected shrapnel and traded the pieces with classmates. It was a tough time.”

After the war, the government promised life would get better, but it got worse. There were food shortages, scarce consumer goods and little hope. “You could work as hard as you wanted and you wouldn’t get ahead without belonging to the Communist Party,” he says. “I was very unsatisfied at that time.”

Seidenberg started sailing in his stepfather’s racing dinghy in Magdeburg, on the River Elbe, and also spent time sailing on the Baltic Sea. Years later, while he was studying to be a naval engineer, the Berlin Wall was erected. “I felt like I was in prison,” he says. “Until that time, it was possible to escape via Berlin. All you had to do was buy a train ticket to East Berlin and walk across the street to West Germany.”

For more than a year, Seidenberg plotted an escape with his friend Hans Steinbrenner. The plan involved a folding two-man kayak. “We bought the boat in the summer of 1963 with the intention of using it in the fall,” he says. “We had intended to practice paddling, but we had no time.”

On October 25, 1963, Steinbrenner called Seidenberg at work and said, “Tonight’s the night” — code words that meant the mission was a go. Seidenberg returned to his apartment to get the kayak, which resembled a tent when it was unassembled. A taxi took him to Steinbrenner’s dorm room, where they assembled the craft. At midnight, the two of them carried the kayak across the promenade and the dunes to the shoreline, where they set off for Gedser, Denmark, 27 miles across the Baltic Sea.

“The sea was flat calm. It was sort of an Indian summer night,” recalls Seidenberg. “At first, the night was dark, and then the clouds opened up and we could see Polaris and use that for navigation. Halfway across, we saw the lighthouse.”

With the escape a success, Seidenberg worked his way through the immigration process and settled in Hamburg for three years. He never paddled a kayak again.

At the time, Canada was running advertisements seeking immigrants to increase its population, so Seidenberg seized the opportunity and moved to Toronto, where he started racing a Finn dinghy despite his light and wiry 160-pound build. In 1973, he won the Finn Canadian Championship, a light-air regatta. He would never be heavy enough for the Finn in big breezes, however, so in 1973 he purchased his first Laser, hull No. 11003. It was the start of a long love affair with the world’s most endearing singlehander. “It is the least expensive, most rewarding way of practicing my sport,” he says.

In 1980, he learned of the inaugural Laser Masters World Championship, but only after the regatta was over. “I would have gone,” he says. “The next year, the Masters Worlds were in the same place, so I decided to take part.” He hasn’t missed a single one since.

While Seidenberg sails the Laser alone, his charming and sociable wife, Fran, is as much his crewmate as she is his soul mate. They met in 1978 when Seidenberg was skiing on Easter vacation. She spoke some German, which impressed him enough to work up the courage to ask her to dinner. After a two-year long-distance relationship, they married.

The more time Seidenberg spent with his Laser, the more he detested its portage. In the early days, competitors carried boats to the water. Alternatively, there were flimsy plastic dollies available from England. “I had one and had repaired it several times,” says Seidenberg. “I decided there must be a better way.”

He pondered a better dolly for three years or so, coming up with vague ideas. Then, in 1989, he sat down and put ideas to paper. The Seidenbergs mortgaged their house, cashed in retirement accounts, and launched Seitech Dollies. Peter was a one-man show, building the dollies and doing the marketing and shipping. At night, after she finished her day job, Fran tended the books.

They relocated to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in 1991, to be closer to where the Laser was manufactured. Peter Johnstone, then owner of Sunfish/Laser, knew Seitech dollies helped sell Lasers, Sunfish, Optimists and other dinghies, so he included Seitech information in his dealer mailers and advertising. After a profitable run, in 2001 the Seidenbergs sold Seitech to Vanguard. At this point, most would be happy with what they had accomplished, but not the Dolly Meister. Seizing on a dolly shortage in 2013, he came out of retirement and started Dynamic Dollies with two partners. The Dynamic wheel’s unique design, with its Delrin ball bearings, spins effortlessly under load.

Seidenberg does, of course, take great pleasure in the independence his dollies offer sailors. “There were 160 Dynamic Dollies at the Laser Masters Worlds in Kingston,” he says. “That was a wonderful sight. I think it’s fair to say my dollies, the Seitech and Dynamic, have contributed to the popularity of dinghy sailing. When I go to regattas and see all of them, it’s such an awesome feeling. It makes me realize my life has been useful, has made a difference.”

Today Seidenberg summers in Rhode Island, and sailors in the area admire him. His reputation as a sportsman and a dedicated competitor precedes him on the international stage.

For example, Jeff Martin, of Falmouth, England, is the executive secretary emeritus of the International Laser Class Association. He has a big presence, a big voice, and he runs the Laser Masters Worlds with an iron fist. But he becomes subdued, as if awed, when he speaks of the Iron Master. Martin says he’s watched Seidenberg pass through the various age brackets, always maintaining a high level of participation and respect among his peers. “When the Masters first started, the maximum age was 60,” says Martin. “Then we saw the top end gradually increase to the point where we had to bring in extra age groups. As Peter has moved through, he’s wanted that, and he has taken the view that if you can do it, I can do it. He seems as keen to me now as when he started. I wish I could emulate him.”

Scott Leith, of Auckland, New Zealand, says he’s inspirational: “He makes me harden up at age 44. I have been world champion only six times. I’d like to win one more than him, so I hope he retires soon.”

Kerry Waraker, of Australia, says: “Peter is a great sailor and ultracompetitive but fair. He won’t wish me luck at a regatta but will go as far as wishing me ‘equal luck.’”

Laser Training Center owner Ari Barshi, of Cabarete, Dominican Republic, says: “At 77 years of age, Peter decided it’s time to perfect his tacks, and decided to pick on me, the 53-year-old youngster, to be his training partner, aka victim. So there we were, doing covering drills, with me trying to escape from Peter, who was ahead and blocking my wind. Every time I had enough of these tacks, Peter would say, ‘Just one more downwind, and then some tacks upwind.’ The fourth time he said that, I did not believe him anymore and just sailed away. He kept on tacking for at least another 20 minutes, with no more than a minute between tacks.”

Then there’s his reputation for being a sportsman. Al Clark, the Laser Radial Grand Master world champion and head coach at Royal Vancouver YC, has a favorite Seidenberg story: “At the Laser Midwinters East Regatta in 2003, I believe, there was a start where many of the top sailors of the day were ready to go with the line being very pin-favored. Peter came in on port and lined up in the perfect spot, below one of the top campaigners.

“This fellow took this as a bit of an insult, as Peter was in his 60s. The sailors backed out and sculled around to beat Peter to the pin. In the end, Peter had a clean start and the other guy went into the pin, and the mark boat anchored at the pin, breaking his tiller.

“There was a lot of yelling and colorful language, and in the end the sailor learned a lesson, apologizing later by letter to Peter, who was, of course, gracious in all of it. He sails hard and fair and will beat you at any age if you give him a chance. He really is unstoppable.”

Terry Neilson, a past world champion from Toronto, says Seidenberg is the most organized sailor he’s ever run across: “He has everything you could ever want to borrow in the back of his car, in alphabetical order. He would see me coming and know that his meticulous inventory of spare parts and tools was about to be ravaged. His initial German distaste for disorganized, bumbling idiots advancing on his inventory would slowly fade, and a smile would appear as he awaited another pathetic request for a plug, batten, screwdriver or telltale.”

The piles of silver accolades commemorating 12 world championships, twice as many regional wins, and more national titles than he can remember are not what drive the Iron Master; it’s incentive to work on his fitness, he says.

While he’ll never boast of it, he does enjoy the occasional praise from younger master sailors who point out his enviable ability to hike and endure long days on the water. “They say, ‘My father is your age, and he can hardly walk. You are hiking out like a youngster,’” he says. “That is a very nice thing to hear.”

Seidenberg knows the Fountain of Youth is his Laser. Without it, he’d be like millions of AARP members who sit idle every day, just passing time. Not him. He’d rather be passing another competitor.