And then there was one… Of the six recently launched, new generation of IMOCA foilers, five entered the Transat Jacques Vabre and of these five, four were forced to abandon. With the only remaining foiler in the race, Banque Populaire, bearing down on Itajai, many questions are being asked about the new boats and if they really are a step in the right direction for ocean racing.

Ask any of the designers, sailors and teams who have seen the foils in action, and the answer is a resounding yes. For several of the retired teams, the damage to the boats was minor, and not seriously threatening, however as time onboard for the teams to familiarize themselves with the new beasts has been minimal, rather than risk the 40 knot winds and high seas, the skippers made the smart choice and brought the boats home safely. With the exception of HUGO BOSS, which has since been recovered.

To really understand if the new generation of IMOCA is the right direction of monohull ocean racing, you need to understand the dynamics behind the foils and the true potential that the lateral appendages hold. Though they put on a disappointing first show, there is more to the young generation of speed machines than they have yet to prove.

So what makes the new IMOCAs so special?

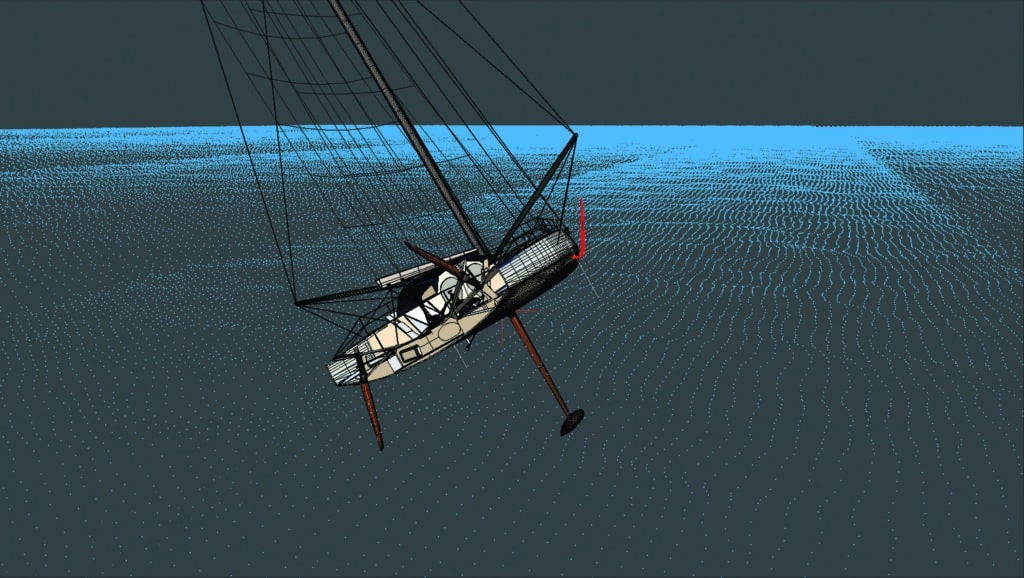

In addition to featuring IMOCA 60 class-rule-mandated wing masts and keels, each of these yachts also features skyward-pointing L-shaped daggerboards. Protruding from the sides of the hull, roughly in line with the canting keel, the appendages are known in IMOCA circles as “Dali foils” in honor of the iconic Spanish artist’s distinctive mustache. Remarkably, the design models say the new foils could shave as many as four days off the Vendée Globe course for those skippers who can master them.

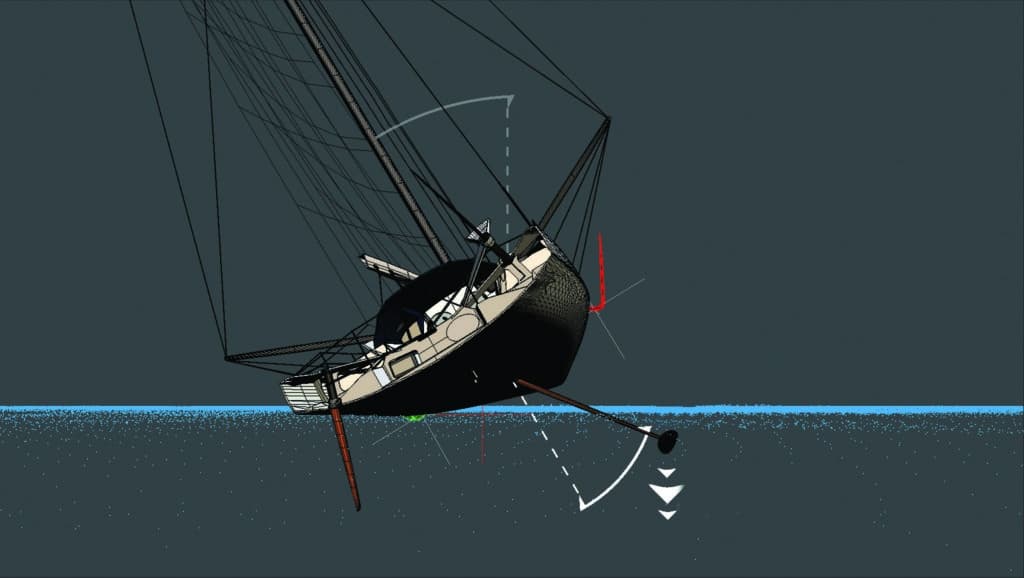

VPLP designer Quentin Lucet, who has been developing the new foils for the past two years, says the objective is to produce a substantial increase in righting moment to counteract the negative effects of an angled keel.

“Our designs set the keel on an angled pivot pin,” says Lucet, “which produces lift, but because it is on the windward side, it has a negative effect on the overall righting moment. To balance this force, the answer was to create a daggerboard that would create lift on the leeward side of the boat and make the yacht stiffer.”

The foils are typically made up of three sections: a straight or slightly curved shaft (around 10 feet); an elbow turn; and a roughly triangular-shaped tip (around 3 feet). As Lucet explains, it’s the elbow and the tip that do all the heavy lifting.

“The elbow is what creates the vertical lift force, while the tip provides the side force to help stop the boat sliding sideways when the keel is canted. The shaft is just there to project the elbow and the tip away from the hull. If we could, we would have designed a foil without a shaft, because we actually want it to be as neutral as possible in terms of lift.”

IMOCA class rules allow only one plane of movement from any underwater appendage. In the case of the foil, this movement is accounted for as the foil moves inboard or outboard of the hull. “That is significant because it means we are not able to alter the angle of attack of the foil by tilting it fore and aft,” says Lucet. “So we are constantly trying to make the shaft as neutral as possible across the range of conditions we can expect when sailing, because any lift could end up working in the wrong direction. We have experimented with asymmetric and symmetric shaft profiles, but asymmetric is currently favored because it creates a smoother transition in the elbow area.”

Early indications are encouraging for the new foil systems — particularly in windy downwind conditions, where the appendages have moved the IMOCA 60 top speed from the high 20s to the low 30s. Less impressive, however, is the new boats’ performance upwind in lighter conditions, where so far the new-style foils have proved to be a drag-inducing hindrance. However, with upwind sailing accounting for 15 percent or less of a typical Vendée Globe track, it’s easy to imagine how prolonged downwind gains compensate for short-term upwind losses.

Although one of the last teams to launch its new boat, Sébastien Josse’s Gitana — the Edmond de Rothschild syndicate — has capitalized on the experience gained from its various foiling-multihull projects to deliver what appears to be a fast and stable setup straight out of the gate. The team’s video footage of Josse with his Transat Jacques Vabre Race co-skipper, Charles Caudrelier, blasting along comfortably in 30-knot winds and big seas off the coast of Brittany, must have struck fear into the hearts of the other teams still struggling to master their foil setups.

“The Gitana team has been playing with foiling boats for a long time in the GC32 and the MOD70, and we know that the key to foiling smoothly is the incidence [angle of attack] of the foil,” says Josse. “Half a degree adjustment in the wrong direction can have an enormous negative effect on the boat’s performance. When you do 35 to 40 knots in a big multihull, you learn quickly what is right and what is wrong. The faster you go, the more small mistakes cost you.

“Sailing the new IMOCA 60 is very different from the monohull sailing that we are used to, but actually quite similar to sailing a foiling multihull. You have the same feeling of the power coming from the foil in that you feel the lift in the same way. In multihulls you sail on the lift of the foil, and now in the IMOCA 60 when you go fast — over 20 knots — you start to have the same feeling.”

The faster he goes, the more righting moment he gets, adds Josse, allowing him to then shed the boat’s water ballast. “This is very different from the previous generation of IMOCA 60s, where to make your boat really powerful you needed to have your ballast tank full.”

In one way, the new foils will make life on board more complex, because the skippers will have to guard against overpowering the standard wing masts by using a too-powerful combination of foil and water ballast. Five or more strain gauges are dotted around the rig to help ward off disaster. The new foils, however, could mean a safer downwind ride in windy conditions.

“The feedback we have been getting is that the foil acts a little bit like a damper,” says Lucet. “Whereas the previous-generation boats would surf with the bow out and then crash down, pushing so much water that the deck was engulfed, what the skippers are saying now is that does not happen with the new foils. If you can get the boat balanced, the ride is much more stable.”

Despite the understandable appeal of the prospect of skimming across the surface rather than plowing through Southern Ocean waves, what is yet to be established is how well the boats’ autopilot systems will be able to cope when the boat is in fast-foil mode. Just how confident will these singlehanded skippers be in leaving the cockpit and grabbing some sleep with the boat at full pace?

“The risk with the new foils, of not being around to release a sheet or empty some ballast, is that you could overload the rig by achieving some righting moment too high for the conditions,” says Lucet. “For example, surging over 30 knots with water ballast would very likely overload the mast. That is why gathering and analyzing data from the rig-load cells is so important, to understand how the loads ramp up or down according to changes in the conditions.”

To the casual observer, the foil packages across the first five boats look very similar in terms of shape and dimension. However, Lucet says briefs from individual teams were wide-ranging.

“The skippers each have their own specific experience, and so we have been designing the foils according to the way each of them wanted to sail or to specify their boats. For example, one skipper might want a boat that is the fastest in the range of 90 to 110 degrees true-wind angle, and another might ask for not the fastest boat but the most versatile boat he could have.

“We were very keen to find out if what we expected to happen really did happen. The first thing to do was to accurately record the data on how the boats behave across a range of conditions and trim, so we could start to work out how to fine-tune the settings of the foils.”

However, before any data-gathering could get underway, the teams had to determine how to sail the new and highly complex IMOCA designs. “These new boats are pretty complicated setups,” says Lucet. “They have wing masts and water ballast, and some of them have around 50 control lines feeding back into the cockpit. Before [the sailors] could start to think about what was going on with the foils, they had to spend quite a bit of time getting all the other systems running smoothly.”

A predominantly light-wind summer in Europe has meant a paucity of data-gathering opportunities in Vendée Globe conditions. A driftathon of a Fastnet Race saw Morgan Lagravière’s Safran finish third behind two old-generation boats, with Armel le Cléac’h on Banque Populaire ironically languishing in the back of the fleet, while now being the only boat left in the Transat in a tight second place..

However, Lagravière says the race and the result revealed little new information about the foils or the new designs in general.

“The boats with foils are made for the type of sailing conditions that can be found in the Southern Ocean in a Vendée Globe: trade winds, strong winds and big waves,” he says. “In light winds, the wide and flat hulls affect the boat’s speed because there is more surface in the water.”

As well as mastering how to balance their boats properly downwind, the six pioneering teams’ other big challenge is how to dramatically improve the dire upwind performance with the new foils. “Outside of 70 degrees wind angle, the foils work really well,” says Josse. “To make the foils work, we need to get to 12 knots as quickly as possible, and that means sailing wider upwind angles — 60 to 65 degrees rather than the 50 to 55 degrees we would like to. It’s like sailing a multihull: First you generate the speed, and then you can go on the wind.

“We need to find other ways to take this side force — maybe we need bigger rudders, or maybe we just need to sail the boat differently.”

While the size and shape of each team’s foils are out there for all to see, data on angles and the depth at which the foils are deployed are kept closely guarded. “That’s a big secret because it’s the key to getting the best performance,” Josse explains. “While we are testing we have a system that allows us to change the angles to get more or less lift, but for racing, the system has to be fixed.”

Design teams are also scrutinizing the roughly 90-degree angle of the foil’s elbow to see if that can unlock a more efficient upwind configuration. “The more you can open the angle of the elbow beyond 90 degrees, the better it is in terms of drag,” says Josse. “However, the more you open it, the worse it is at stopping the boat going sideways.

“Looking at it another way: To achieve maximum side-force resistance, you want the tip to be as vertical as possible when the boat heels. But the more you close the angle of the elbow to achieve that, the more you increase the drag, and overall the foil becomes less efficient. For sure, there is plenty of work to do to find the angle that is the best compromise.”

Josse says he and the skippers of the other new boats are confident in the design logic behind the new foils. Less certain is whether the foils will evolve quickly enough to be used for the Vendée Globe. “At the end of the day we have to remember that the goal is to win,” he says. “And to do that, we have to find the right compromise between pushing the development and the performance of the boat.”

With the new IMOCAs back on shore, the eyes are on the finish for the class in Itajai, expected sometime on Wednesday, November 11 to see if Banque Populaire can out-pace PRB and prove the foils’ worth. Regardless of the result, it is clear that the new generation needs some work before they start shaving days off the Vendee Globe time, but the skippers and the teams behind them are confident that once the bugs are fixed, and the flaws remedied, the speed machines will do just that.

Read more: Transat Jacques Vabre – IMOCA class

SAILING – SAFRAN 2 AERIAL – 160915