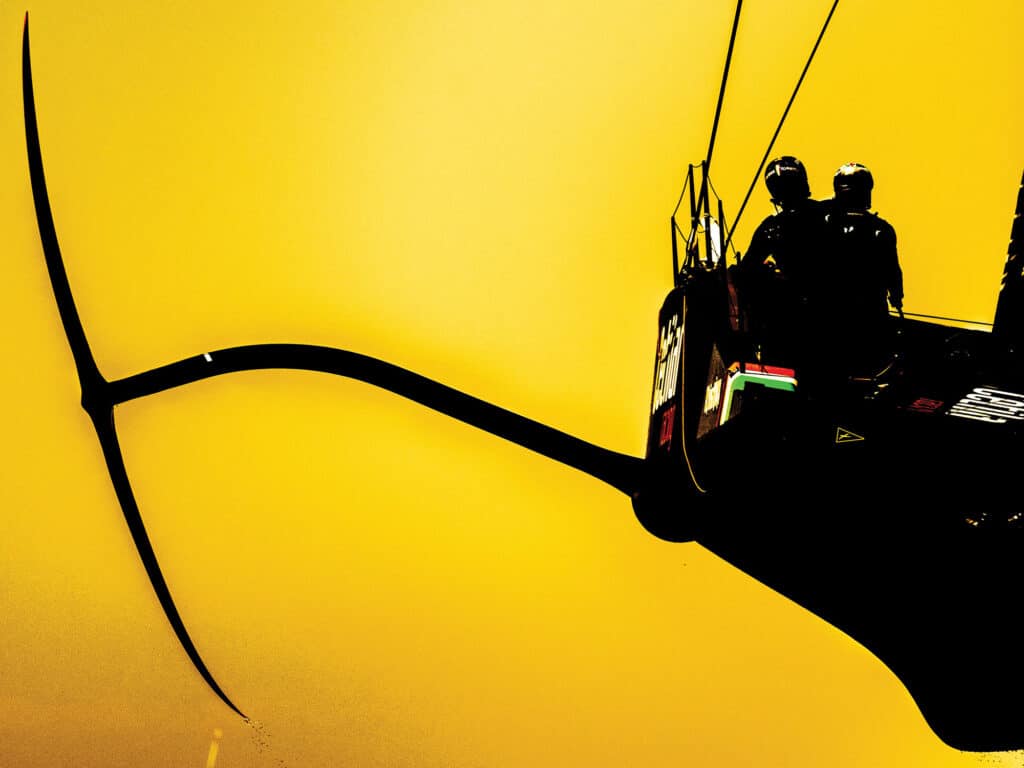

Love it or hate it, performance yachting has taken a quantum leap over the last two decades with the proliferation of foiling, which has permeated throughout the sport—from the America’s Cup to all manners of wind-driven board sports. In Italy last summer, however, a new and curious chapter in foiling arrived with the launch of Roberto Lacorte’s FlyingNikka. The sleek black maxi bears a striking resemblance to an AC75, but at 60 feet, it is far shorter and—significantly—has an original remit for a foiler: to compete in maxi fleet races, both inshore and offshore.

Lacorte, who founded the pharmaceuticals company PharmaNutra Group in 2003 with his M32 sailor and brother Andrea, is a keen sailor. For many years he raced in the maxi fleet aboard his Mills-Vismara 62 racer-cruiser SuperNikka. However, the 54-year-old also prefers speed—his other sport of choice being motorcar racing. Since 2017, he has regularly competed in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and today races North America’s IMSA SportsCar Championship.

His penchant for speed now extends to his yachting. Initially, Lacorte was going to replace SuperNikka with a longer racing maxi, but after a season campaigning a Persico 69F foiler and inspired by the AC75 and other foilers, he began wondering whether his next maxi should or could fly too.

Given the constraints of creating a minimum-size (60-foot) maxi that foils and take part in conventional races while on a budget with limits and without an army of shore crew, he assembled a team to work on the new project. Led by North Sails Italy’s Alessio Razeto, this included Nacra 17 Olympian Lorenzo Bressani, project manager Micky Costa, and Mark Mills leading the design. Brought on board for R&D was KND, while Pure Design & Engineering handled the engineering. Nat Shaver (ex-ETNZ and American Magic, now INEOS Britannia) designed the foils. King Marine in Valencia built and assembled the boat, while Re Fraschini in Italy fabricated the foils.

Mills says he was initially skeptical whether FlyingNikka could be created without America’s Cup resources, but he eventually concluded that such a foiler could be realized if it were kept simple, meaning free from the constraints of the AC75 rule: A motor could power the hydraulic package, controlling almost everything from sails to foils, reducing crew, and making grinders and cyclors redundant. Similarly, with no restrictions, ride height and pitch could be controlled automatically.

After six months spent examining all options, including IMOCA-style retracting Dali foils, FlyingNikka’s design was unveiled with an AC75-style “flip-up” foil-cant arms configuration.

Aside from its size and intended use, FlyingNikka has two significant differences to an AC75. The foils cant up to weather and down to leeward like an AC75. However, they develop lift by altering the pitch of the entire wingspan (i.e., the whole wing articulates laterally around the bottom of the arm, typically from zero to 15 degrees), unlike the AC75 system where the foil arm and wing are fixed and lift develops from an airplane-style flap on the wing’s trailing edge.

This neatly avoids a significant issue of AC75 foil design and engineering, making a flap that operates reliably on the back of a bendy T-foil. FlyingNikka’s simpler flap-free arrangement means more freedom for its foils to deflect and the wingtips to unload. Altering the incidence of the entire wing also produces significantly more lift compared to a flap, in theory enabling the boat to take off in lighter winds.

Significant too is that while an AC75’s wings are ballasted—made of lead and steel, and some with lead bulbs—FlyingNikka’s wings are made from carbon fiber instead. Being substantially lighter, they have been far easier to engineer and manufacture.

Working in conjunction with the main foils is the rudder elevator. Its lift adjusts by raking the entire rudder. The bottom bearing is mounted in a transom scoop, where the rudder stock rotates about a vertical axis as usual and a lateral axis to permit the elevator to be raked by plus or minus 6 degrees via a hydraulic ram pushing and pulling the top of the stock.

To enter traditional races, FlyingNikka must comply with the Offshore Special Regs’ Category 3 STIX stability requirements, so it has a keel, which an AC75 does not. At 2,000 kilograms, this keel is small but significant given the boat weighs only 7 tons. Two extra tons on a foiling boat is costly—Lacorte reckons it chops 4 to 5 knots off their top speed. The keel, however, does have several benefits. Along with the arm of the leeward foil, the keel prevents leeway. Between the foil arm and the keel, FlyingNikka enjoys “negative leeway” (like boats with a trim tab on the keel). It also means the foils don’t need to be ballasted (unlike the AC75). It does, however, lose the righting-moment benefit of an AC75’s ballasted foil when it cants to weather.

Significant for FlyingNikka’s intended use in light winds, the keel makes the boat more manageable and less likely to capsize when its foils are providing minimal lift. In practice, it also smooths the transition between flying and displacement modes. In the future, the team might make record attempts when its keel could be removed, although it would still need some arrangement for the engine water intake (otherwise located in the keel).

The boat was first launched in early May, and its successful flight at the very outset was most remarkable for such an experimental platform. This was mainly down to the R&D effort put in by the design team, and especially its access to America’s Cup CFD and engineering tools. Since then, FlyingNikka competed at the Maxi Yacht Rolex Cup in Sardinia and at Les Voiles de St. Tropez. The latter was disappointingly windless, although valuable lessons were learned about how to sail it in displacement mode. But Lacorte showed the boat’s extraordinary potential in the former, starting last in its own class and sailing through the fleet.

To enter fleet races, the boat has been given a stratospheric IRC rating of 3.866, so it is unlikely ever to win under corrected time. (The previous IRC TCC high scorer was the ClubSwan 125 Skorpios at a mere 2.149). Lacorte seems satisfied simply being out on the racecourse.

In terms of performance, FlyingNikka is not designed for peak speeds, although the sailing team managed 27 knots upwind and 38 knots downwind at respectable angles, with more to come. The boat, including the foil package, is designed for conditions typical of the Med, i.e., light. As a result, it has larger foils, requiring less wind to take off, which comes at the expense of top speed. Downwind, FlyingNikka needs around 9 knots of wind to fly, 10 to fly well and 12-plus to achieve optimal VMG, at which point it is making close to 30 knots.

The team is examining how to best sail the boat in displacement mode when it is too light to foil. Far from being a complete write-off, the boat can still make good progress relying on its ultralight displacement and substantial sail area. Trickiest is the transition between nonfoiling and foiling because there are techniques such as sailing lower angles or increasing foil rake that can permit early takeoff. But the poor VMG and excess drag required to achieve this can be slower than sailing in displacement mode.

Lacorte is also learning the oddities of handling a boat that can sail at more than twice the windspeed. While foiling, the apparent wind angle is rarely more than 50 degrees, even downwind. Upwind can be only 19 degrees.

All foiling boats require slightly different techniques to perform maneuvers well and remain airborne. “You have to move and steer a lot,” Lacorte explains. “It is different compared to a normal boat. It is necessary to maintain flow over the foil, to keep pressure on it, and carry out maneuvers in a strong, fast way. Then you generate incredible G-force, like a sports car. You have to hang on, otherwise you risk falling overboard.”

With Lacorte, there are just five crew, thanks to the engine-powered hydraulics and automation. As with the AC75, the crew resides in fore- and aft-oriented trenches, with the helmsman forward to windward with a screen and a wheel in front of him, and the flight controller forward and to leeward. Aft are the mainsail and headsail trimmers, who swap sides during maneuvers. Farthest aft, the navigator and the systems operator are stationary. Each crew, including the driver, controls an array of waterproof buttons operating the hydraulics, including some safety ones too, such as to dump sheets. Dropping and raising the foils is done via foot pedals. Inboard of each cockpit is a powered winch used for the A1 sheet, halyards and furling lines.

Part of the secret to sailing FlyingNikka is the automation of the foil wing’s articulation in conjunction with that of the rudder elevator rake. This, for example, enables the crew to adjust ride height and fore and aft trim continuously. At split-second intervals, the automation then adjusts the pitch of the foil wing and rudder rake to make this happen. This requires the software to be trained, partly through the crew teaching it, but also through its own intelligence, learning from how the crew operate the boat. Also vital is the system continuously knowing the exact orientation (pitch, yaw and roll), movement and acceleration of the yacht. As a result, FlyingNikka is littered with rate gyros and accelerometers monitoring its every motion.

Essential too is the speed of the hydraulics. To ensure maximum performance, the system operates at a substantial 500 mb of pressure, so there is no need for stored power, although it does require the engine to run constantly.

Above the deck, the rotating rig is a conventional two-spreader affair but without runners. The mainsheet provides much of the forestay tension. Given the boat’s speed, sails are ultra-flat and the wardrobe is limited—just a mainsail with a low telescopic boom (outhaul controlled by the boom being pumped in or out at the gooseneck), with a deck sweeper and three jibs, the smallest on an inner forestay, plus an A1 for use in displacement mode. The aim, according to sailmaker Alessio Razeto, is to have the minimum sails necessary to get the boat flying because they become drag rather than driving force and need to be reduced rapidly afterward.

FlyingNikka is capable of all “the foiler moves,” flying both downwind and upwind, and foiling jibes and tacks. These will be refined with practice, but it is this voyage into the unknown that Lacorte and his highly experienced crew relish. And where FlyingNikka is breaking new ground is in Lacorte’s desire to race it offshore. Typically, this type of foil configuration doesn’t like waves—foils suddenly stop working when they are not immersed—while a flying hull colliding with a wavetop can damage crew and the boat due to the deceleration and the resulting loads. However, Lacorte says he is pleased with how well FlyingNikka is performing in 6-foot waves thus far. This is partly due to the AC75-style “bustle” (the long, shallow skeg that runs down the length of the hull’s centerline), designed to ease the transition between displacement sailing and foiling. It is also due to the boat’s center of gravity being quite far aft, which means it typically touches down stern-first. Razeto admits his biggest fear is “an uncontrolled takeoff with the bow up.” Normally, it is the back of the boat that lands first when this happens. “We have done that a couple of times,” he says. “With a nosedive, a lot of water comes over the boat, but it is not really dangerous.” However, the stern reimmersing first appears to be substantially less dramatic than going from foiling into a giant nosedive.

With its first Med season in the books, modifications are currently being made to FlyingNikka before next year’s 151 Miglia-Trofeo Cetilar, followed by the Rolex Giraglia and the Rolex Middle Sea Race. Female tooling for FlyingNikka remains at King Marine, ready for any additional brave individuals with a craving for speed to buy into Lacorte’s vision with a budget that Lacorte reckons is less than that of a Maxi 72.