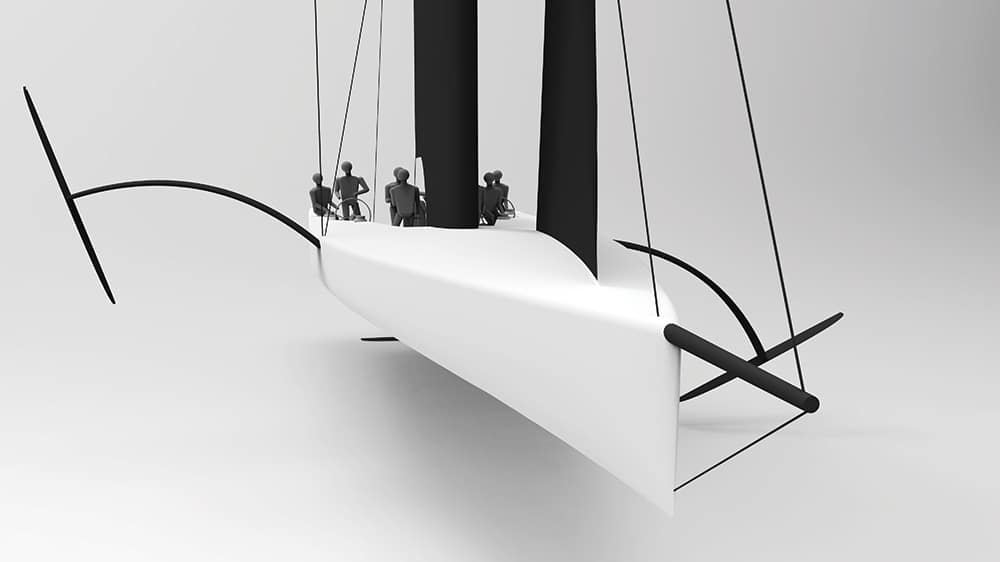

It’s been name-called the three-legged gecko, the freak and countless others, but designers and engineers tasked with delivering this first generation of the AC75 proposed by the America’s Cup defender and challenger of record use one word to describe it: freedom.

“The platform is known,” says Adolfo Carrau, with the design firm Botin Partners. Botin is designing for the American challenger Bella Mente Quantum Racing. “The demands are similar to the multihull [used for the 34th America’s Cup], and at the end of the day, it’s a foiling boat. A lot of work was done by teams in the last campaign, work to improve the tools required to design foils, and most of the work these guys were doing continues. But still, there is not a lot of tradition in this boat.”

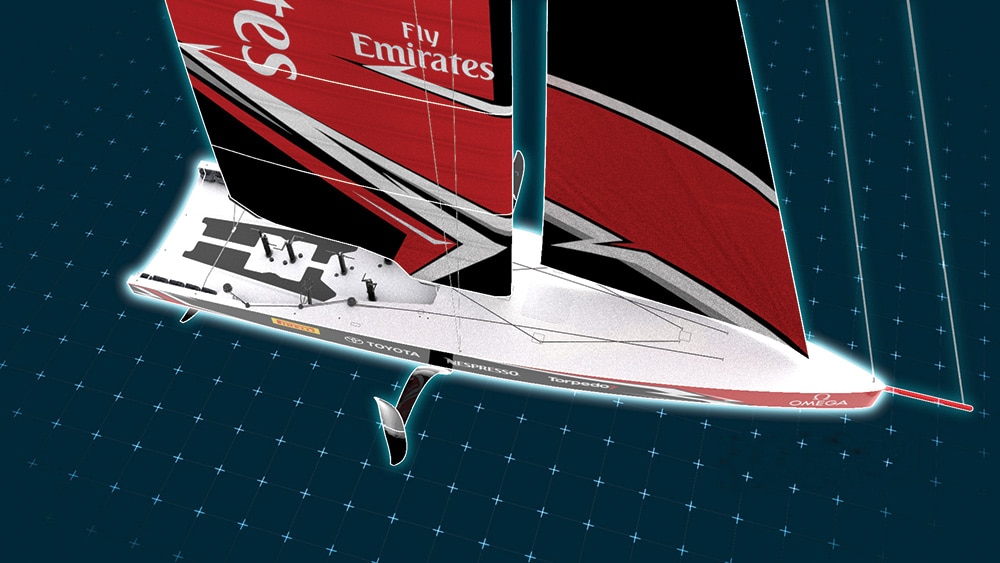

The only distant tradition to the Cup, of course, is the monohull, a different take on which was presented by Emirates Team New Zealand — the clever defender that almost dethroned Oracle Team USA in San Francisco in 2013, and then did so in Bermuda in 2017. With both New Zealand challenges, the Kiwis were steps ahead with their foiling initiatives, and their undeniable foiling-technology prowess is their strength. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the AC75 is essentially a big, lightweight surfboard meant to fly.

With the AC multihulls came plenty of righting moments from the platform. With the AC75, that righting moment will come from the foils. As awkward and bizarre as the concept might appear to traditionalists, simulations conducted at Botin while they await the class rules confirm the AC75 concept will work.

“Our in-house simulations confirm what they were predicting,” says Carrau. “Which is it should be able to foil in over 9 knots of true wind — both upwind and downwind.”

It’s an interesting concept that doesn’t exist at the moment, he adds, so the design team must rely heavily on dynamic simulations in the upcoming year. “It’s going to be an interesting Cup cycle because of this new concept,” he says. “Everyone will be relying on their technology to design their boat.”

In other words, the boats will be designed by the computer. Only when they have something tangible can they start applying experience and sailor-driven enhancements. “It’s hard for the sailors and designers at this stage to anticipate how the boat will behave in every condition,” he says. “It’s so completely new.”

Over time, Carrau and his peers have been limited by processing power of the simulators. Creating from scratch at this level is about big data and speed, he says. Emirates Team New Zealand doubled down its time and money on a good simulator in advance of the 34th Cup cycle — more so, he says, than any other team.

Unique as the AC75 might appear to the wider public, the concept is not all that foreign to sailors. In a sense, it’s like a giant International Moth, relying on the active foil to produce most of the vertical lift and side force required to lift the hull free of the ocean’s grip. A rudder elevator corrects pitch angle and contributes to vertical lift as well; early simulations confirm as much. Without a detailed version of the AC75 rule, however, plenty of guesswork remains: the dimensions of the foils and the freedom of where all the associated bits and pieces can be positioned.

The other significant unknown for Botin’s early efforts is the AC75’s rig concept and geometry. What it will ultimately be — soft or hard sail, or a combination of both — is essential intelligence. The rigid wing of the AC50s delivered a lot of power for foiling maneuvers, power that would be lost with a soft sail as it passes through the wind.

The AC75’s ultimate appearance will be dictated by the intended nature of the racing format itself. In the pre-start, for example, the traditional dial-ups will be a big area to try to understand and simulate with a boat lacking a keel and bulb. “That’s where part of the rule development is happening now — the amount of ballast on those struts,” says Carrau. “Ensuring there is enough initial stability to do pre-start maneuvers and dial-ups without capsizing the boat.”

There are more unknowns out of the gate, which appeals to Carrau and his colleagues. “It’s going to be challenging being the first on these new boats, with very compressed timelines to build the boat,” he says.

By compressed, he means Boat No. 1 should be in the water by late March 2019. Seventy-five feet is a big boat, and a complex one at that.

While the defender, by nature of dictating the terms of the regatta in Auckland in March 2021 does have a leg up (or maybe that’s a foil up), the relatively clean slate of the AC75 is an opportunity for others. Among the challengers, he says, the playing field is level. The goal is to outsmart the defender at its own game.

“Right now, they’re a foiling team, so they played that well” in designing the AC75, he says. The boat reflects where Team New Zealand feels most confident — in a foiling boat and relying on a simulator to make decisions.

“The concept and physics of the boat are not the most difficult part,” he adds. “Mechanically it’s going to be difficult to engineer all the systems, and everything depends on how much freedom they allow in the rule for the flight-control systems and so on.”

Of note are the systems that will be required to manage the ballasted foils. Whereas the AC50’s foils were smash-drop entry, the AC75’s foils will essentially enter the water at an angle, which Carrau says will help with ventilation issues that prevent foiling tacks and jibes. At the same time, he cautions, with straight-line sailing, the leeward foil tip must remain submerged to prevent ventilation. From a handling point of view, it will be important to get the optimum foil depth to the water’s surface.

Experience with multihull engineering before the previous Cup led to reliable structures, but with this boat, says Carrau, there is no true starting point. “We have to reimagine the new load cases and the worst-case scenarios that will happen with this boat,” he says, “and then build in the proper safety factor for each component, for an unknown boat. That’s the biggest short-term challenge.”

The challenge now is the freedom in the rule and delving deep into the simulator for an opportunity and a better idea. “That’s the game,” he says, “and that’s how we are preparing ourselves.”