Drawing pistols at dawn, two sailors acknowledged their seconds standing by and marched off 15 paces beneath the moss-covered oaks of the Grand Hotel in Point Clear, Ala. The men turned and fired to settle the affair of honor earned the previous evening over a perceived slight to a young woman at the post-regatta ball. As the smoke from their pistols joined the cool morning mist, the men were left standing—the result of a misfire and a poorly aimed shot. Both parties agreed that honor had been restored, and the matter was settled.

Newspaper reports are vague as to which schooners the dueling gentlemen crewed on back in 1852, but the revered tradition of Southern YC’s Race to the Coast, and its stories, live on. First officially raced on July 4, 1850, the Race to the Coast is the oldest still running point-to-point distance race in the United States and the second oldest regatta after New York YC’s Around the Island Race, which traces its roots to 1845. Today, the regatta follows a 50-mile steeplechase format along a course that has been raced for 163 years—minus a few finish deviations over the years and the interruption during the Civil War when New Orleans fell to Union forces.

The regatta owes its birth to an annual migration of wealthy cotton brokers, bankers, and sugar plantation owners who fled New Orleans with their families during the summer months when heat and chronic yellow fever epidemics would strike the city. Maintaining residences along the coast, and sailing being the primary method of transportation, the men on their schooners naturally made wagers. Over time, the Race to the Coast gained structure until it became an official regatta after the formation of Southern YC in 1849.

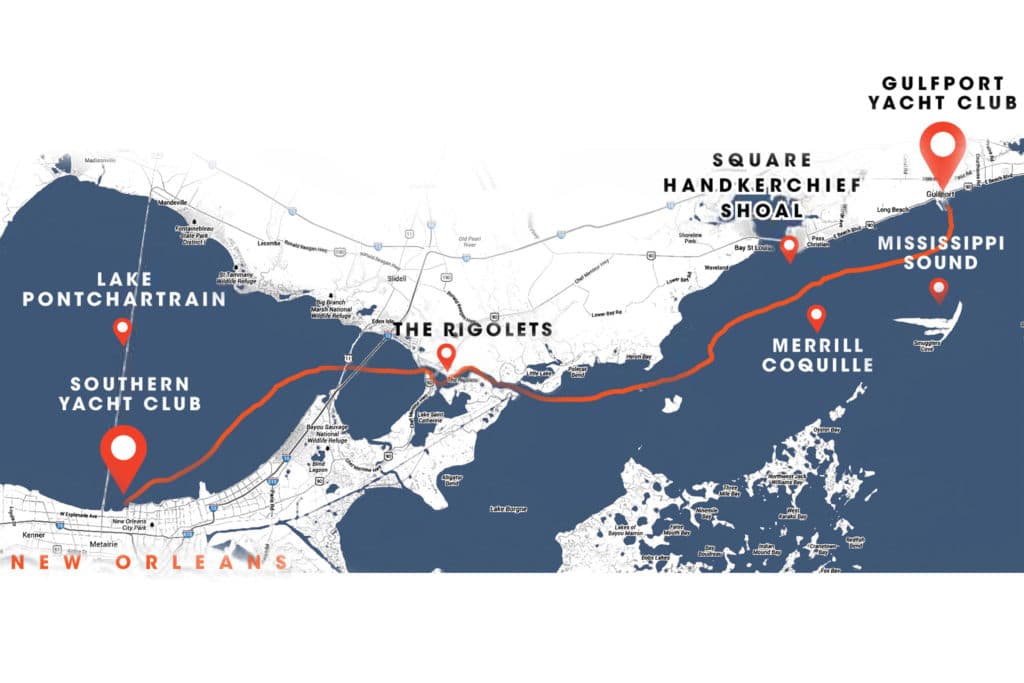

In 1850, the boats and crews took their start at New Orleans’ West End and made their way through the historically light summer winds on the 633-mile Lake Pontchartrain, before transiting the Rigolets (RIG-uh-LEES) Pass, snaking through the marsh and leading into the Mississippi Sound. Southern YC’s regatta now runs on a set course from New Orleans to Gulfport, on the Mississippi Coast, and has the added dimensions of navigating several railroad, highway, and interstate bridges that transect the beautiful, but eroding marshes that lead into open waters.

Stewart “Tootie” Barnett, Jr., a longtime SYC Race Committee stalwart who has overseen the race for many years, perfectly explained the rule of thumb for navigating the pass a few years back: “In the Rigolets, the bottom comes up real short. When it drops from 21 to 20 feet, tack, because in another boatlength, it will be six feet.”

As a feeder race for the 100-mile Gulfport to Pensacola regatta, Race to the Coast drew upwards of 70 boats in its prime. In an effort to boost participation in 2013, the two regattas were scored together as the Sawgrass Offshore Series—the same will be true for the 2014 event, to be held on June 14.

Last year, light summer winds greeted 19 boats ranging from a Stoner 25, helmed by Mini Transat sailor Ryan Finn, to the Melges 32, Rougarou raced by Bert Benrud and 2004 Olympic silver medalist Johnny Lovell. Onboard Bill Provensal’s red-hulled Cal 48 Tiare—which has gained legendary status on the Gulf Coast since 1967, holding multiple line honors and records in everything from buoy racing in the Gulf Yachting Association’s Challenge Cup to distance racing to Mexico—it’s easy to feel connected to the race’s history. On this unique course, forts that are centuries old subside in the marsh grass, while brown pelicans perch on the bones of ancient lighthouses and fishing camps lost in storms.

Tiare crewmember Billy Marchal has sailed the Race to the Coast for most of his life and calls it the “Grandfather of Distance Races.” He says, “Prior to the advent of Loran-C and GPS, when you had to read an actual chart and understand lights, numerous yachts found themselves hard aground on shell banks or in the marsh.”

But it’s an uncommon occurrence in this day and age. Even though the race is well known for the transit of the Rigolets, channel markers and GPS now assist sailors plying the swampy straits. This is a struggling stretch of American coastline. A football field of Louisiana’s vital marsh erodes into the Gulf of Mexico every 45 minutes, and because of this erosion, the Rigolets has grown wider and easier to navigate.

Under spinnaker in the light air on Tiare, the first pair of old adjacent railroad and highway bridges appear after the first few hours sailing downwind on the lake. These obstructions are part of the modern status quo when transiting the Rigolets—they were not constructed with racing sailboats in mind. We radio ahead for clearance; motoring during bridge closures is allowed in the sailing instructions as “bridge time.” Even today, though, it’s not surprising to hear the clueless bridge operators nervously comment over the radio, “You can’t pass with those balloons up!”

We continue into the Mississippi Sound, which offers the beauty of sailing along the barrier islands that make up the Gulf Islands National Seashore, while the oyster beds of Merrill Coquille and Square Handkerchief Shoal keep the helmsmen honest. Later in the day, thunderstorms bring heavy winds. On the run through Mississippi Sound, locals understand that these waters can kick up rapid, considerable chop with the potential for 6-foot swells in short frequency.

As we turn at the Gulfport sea buoy, the final stretch takes us along the sandy, oak-lined coast to Gulfport YC, where we fold the sails and coil the lines—just as sailors have been doing here for nearly two centuries, that pair of gritty duelers included.