The International Sailing Federation has published its 2015 Supplement to The Case Book for 2013-2016, which includes three new cases, each of which contains a helpful interpretation of an important rule. I will summarize these cases below, with my opinions on why they’re worth studying. The cases are available at www.sailing.org/documents/caseandcall/case-book.php

Rule 18.3: Tacking in the Zone

If a boat in the zone passes head to wind and is then on the same tack as a boat that is fetching the mark, Rule 18.2 does not thereafter apply between them. The boat that changed tack (a) shall not cause the other boat to sail above close-hauled to avoid contact or prevent the other boat from passing the mark on the required side, and (b) shall give mark-room if the other boat becomes overlapped inside her.

Case 133: Rule 18.3, Tacking in the Zone

Rule 18.3 is intended to help a big fleet round the windward mark in an orderly way when boats are required to leave the mark to port. It rewards boats that approach the zone on starboard tack. It does not automatically penalize a boat that enters the zone on port tack and then tacks to starboard, but it makes such an approach to the windward mark risky when other boats are nearby. Cases 93 and 95 show how Rule 18.3 applies to incidents involving two boats. New Case 133 is the first case to cover a three-boat incident.

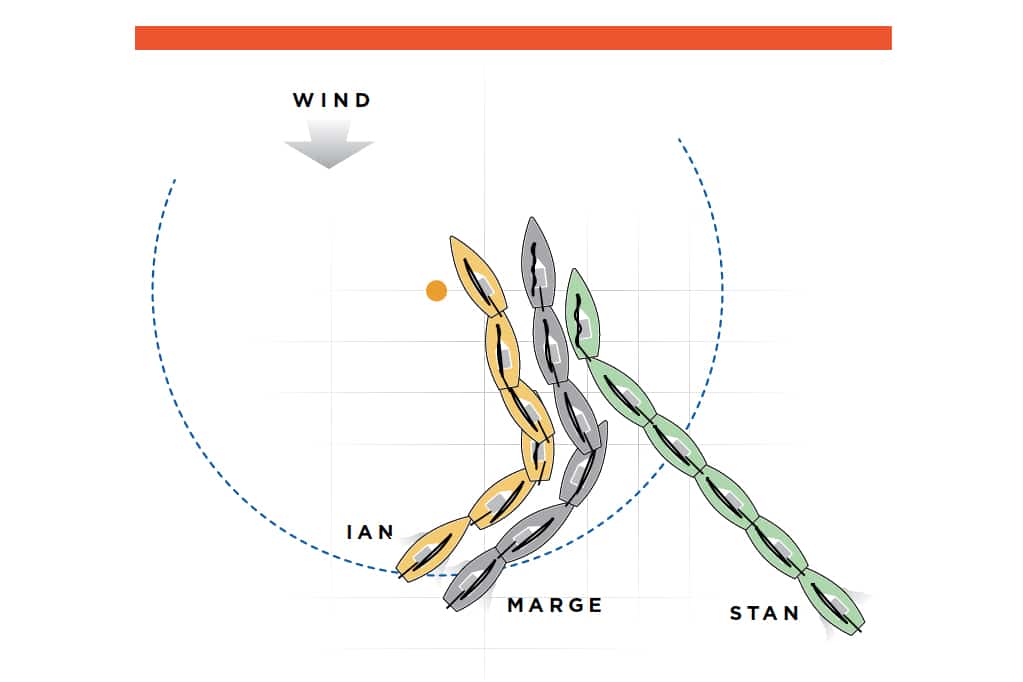

As the diagram shows, Stan had been on starboard for several lengths before he reached the zone. He was sailing close-hauled and fetching the mark. Ian and Marge entered the zone on port. Marge could’ve hailed Ian for “Room to tack” under Rule 20, but she did not. After Position 2, Ian decided he could tack and fetch the mark. Ian passed head to wind and Marge then did the same. As Ian and Marge tacked, Stan continued to sail closehauled, and there was space for one boat, not two, to pass between Stan and the mark. Between Positions 4 and 5, Ian luffed to round the mark. Marge luffed in response and caused Stan to sail above closehauled. There was no contact, and no boat took a Two-Turns Penalty. Stan and Marge both protested Ian. The case answers two questions: How does Rule 18.3 apply to this incident, and what should the decision be? After Ian and Marge turned past head to wind, each of them was on the same tack as Stan who was fetching the mark. Therefore, Rule 18.3 applied between Ian and Stan and between Marge and Stan. When Ian and Marge luffed between Positions 4 and 5, they caused Stan to sail above closehauled to avoid contact, and therefore both broke Rule 18.3(a). Marge, however, was compelled to luff by Ian’s luff, and so, under Rule 64.1(a), Marge was exonerated for breaking Rule 18.3(a).

When Ian passed head to wind he became a starboard-tack boat fetching the mark. A moment later, when Marge passed head to wind, she was then on the same tack as Ian. For these reasons, Rule 18.3 also applied between Marge and Ian. As Marge tacked, Ian became overlapped inside her, and therefore Rule 18.3(b) required her to give Ian mark-room, including space for Ian to comply with his obligations under the rules of Part 2 (see the definitions Room and Mark-Room). Marge did not give Ian space to comply with Rule 18.3(a), which is a rule of Part 2, and so Marge broke Rule 18.3(b).

In sum, both Ian and Marge are disqualified—Ian for breaking Rule 18.3(a) and Marge for breaking Rule 18.3(b). This case sends a strong warning to port-tack boats not to tack in the vicinity of a starboard-tack boat fetching the windward mark. There was space for one boat to pass between Stan and the mark without causing Stan to sail above closehauled, but when both Ian and Marge tried to fit into that space, both of them were disqualified.

Definition: Proper Course

A course a boat would sail to finish as soon as possible in the absence of the other boats referred to in the rule using the term. A boat has no proper course before her starting signal.

Case 134: Proper Course

This case provides a new and helpful discussion of the definition Proper Course. Two one-design boats, Will and Lou, had just rounded the windward mark with Lou clear astern. The next leg was directly downwind to the leeward mark. Will slowed because of trouble hoisting his spinnaker, and the boats became overlapped with Lou close to leeward of Will. As a result, Rule 17 applied and it prohibited Lou from sailing above his proper course. For tactical reasons based on the series scores, Lou continued sailing with his jib, in order to push Will back in the fleet. Lou sailed the course that gave him the best VMG (velocity made good toward the next mark) for a boat sailing with a jib. That course was higher than the course that would have given him the best VMG if his spinnaker were set. Will protested Lou for breaking Rule 17 by sailing above his proper course. In the hearing, Lou testified that, in the absence of Will, he would’ve set his spinnaker and sailed a faster, lower course.

The case answers the question, “Did Lou break Rule 17?” Here’s a summary of the answer.

A boat’s proper course at any moment depends on the existing conditions, including the wind strength and direction, the pattern of gusts and lulls in the wind, the waves, the current, the physical characteristics of the boat’s hull and equipment, and the sails she is using at that time. While Lou was sailing with his jib set, his proper course was the course that gave him the best VMG with a jib. Lou didn’t sail above that course so he didn’t break Rule 17.

There’s no requirement in any racing rule for a boat to hoist her spinnaker at any particular time. There could be a variety of reasons, including tactical considerations, why a boat would delay setting a spinnaker. Therefore, even though Lou stated that in the absence of Will he would have set his spinnaker and sailed a lower course, he broke no rule by continuing to sail with his jib. (Case 78 also discusses tactics that interfere with or hinder another boat’s progress.)

Rule 62.1(b): Redress

A request for redress or a protest committee’s decision to consider redress shall be based on a claim or possibility that a boat’s score in a race or series has been or may be, through no fault of her own, made significantly worse by injury or physical damage because of the action of a boat that was breaking a rule of Part 2 or of a vessel not racing that was required to keep clear.

Case 135: Rule 62.1(b): Physical Damage and Redress

Case 135 interprets the phrase in Rule 62.1(b), “physical damage because of the action of a boat that was breaking a rule of Part 2.” The case describes two incidents in which redress may be given even though physical damage wasn’t directly caused by a collision with the boat that broke a rule of Part 2.

In the first of these two incidents, Paul on port tack and Sal on starboard were on a collision course on a beat to windward in strong wind. Paul didn’t change course and, when it became clear to Sal that Paul wasn’t keeping clear, Sal immediately crash tacked onto port to avoid a serious collision. There was contact, but no damage. However, while Sal was tacking, she capsized, and in capsizing, she fell, damaging her tiller. After she righted her boat, the tiller couldn’t be repaired and she retired. Paul took a Two-Turns Penalty, and Sal requested redress under rule 62.1(b). The case states that Sal is entitled to redress provided the protest committee concludes that (1) Sal took avoiding action as soon as it was clear that Paul wasn’t keeping clear; (2) the capsize and Sal’s fall were the result of Paul not keeping clear, not the result of poor seamanship by Sal; and (3) the damage wasn’t due to Sal’s tiller previously having been in poor condition.

In the second incident, Amy and Ben were on a collision course in strong wind, with Amy required to keep clear of Ben. Amy held her course and, when it became clear to Ben that Amy was not keeping clear, Ben immediately and rapidly made a large course change to avoid Amy. There was no contact between Amy and Ben, but, while maneuvering to avoid Amy, Ben collided with Charlie, a third boat nearby. Charlie’s boat was damaged and he lost several places. Amy took a Two-Turns Penalty and finished the race. Charlie requested redress under rule 62.1(b).

The case states that Charlie is entitled to redress provided that the protest committee concludes that (1) Ben took avoiding action as soon as it was clear that Amy was not keeping clear; (2) the damage to Charlie was the result of Amy not keeping clear and not the result of poor seamanship by Ben; and (3) after Ben began to change course, it was not reasonably possible for Charlie to have avoided the collision and resulting damage.

Here’s the take-away from Case 135: If a boat breaks a rule of Part 2 by failing to keep clear, the right-of way boat, or a third boat, may be entitled to redress if she is physically damaged, even if the damage isn’t caused directly by a collision with the boat that was required to keep clear.

E-mail for Dick Rose may be sent to rules@sailingworld.com.