The America’s Cup is about high-performance sailing and cutting-edge design and technology. Today, it must also embrace the elevated skill level required to sail such high-performance craft. Match racing, which is the Cup’s traditional format, is a discipline that adapts to the type of boat being used for the competition. Dial-ups, slam dunks and tacking duels have evolved, and the same thing will happen with the AC75. New moves will be coined in the years to come, and certain maneuvers will be equally, if not more, difficult to execute. Youth and athleticism are required to sail the latest America’s Cup machines, but ultimately, the success of each effort begins with the design and construction of the platform itself.

One of the first steps an America’s Cup team will take when drilling into a new design rule is to paint a rough picture of what the rule intends, which requires extensive drawings and comparisons. The second step involves creating a base-line hull, appendage and sail plan for input into a proprietary velocity-prediction program. A good VPP can give clear indications for what variations within a design rule are worth exploring with regard to performance.

The VPP requires a tremendous amount of input and accurate data to support the optimization process. It will be one of the central clearinghouses for design ideas and what-ifs for the AC75, but it also serves as the backbone for race models and race simulators that introduce a heap of additional variables. Many questions can be answered with a combination of these tools, but reality often brings unexpected results, and many lessons can be learned by building something real.

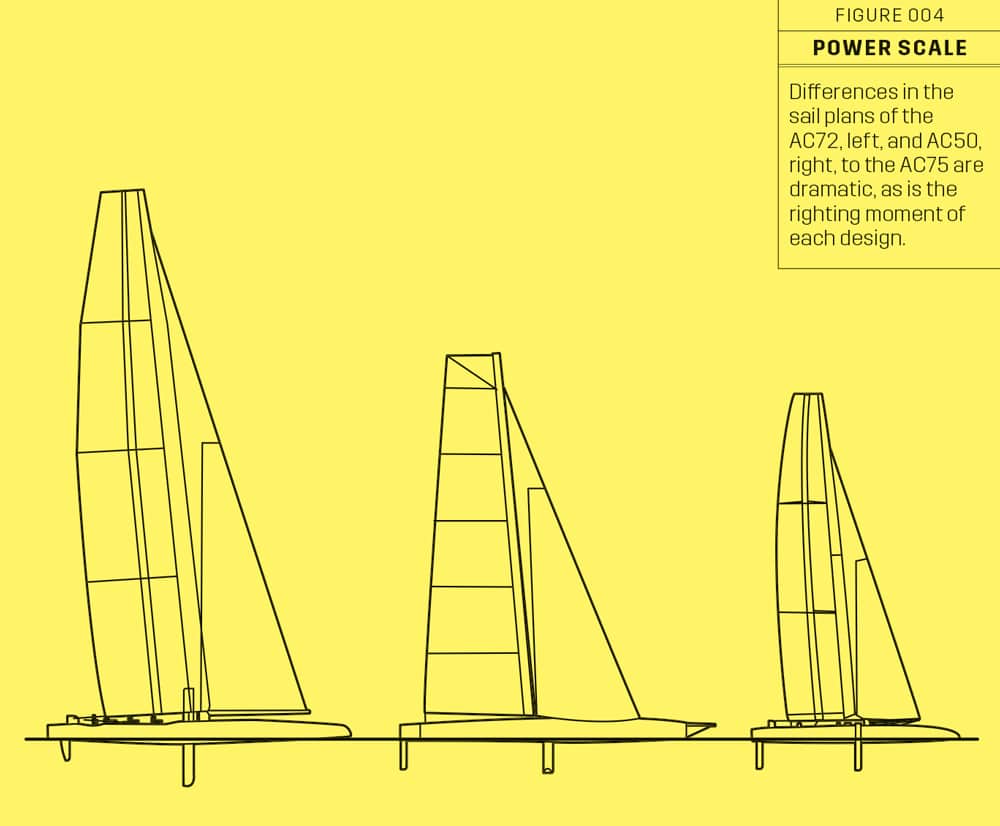

The base-line design will evolve as quickly as teams receive results, and design iterations will continue until build deadlines. With any new boat design, and especially in a new class, no one area can be ignored because there is no status quo to fall back to. There is a lot of work ahead, for challengers and defender alike, but the two previous America’s Cup catamaran classes — the AC72 and the AC50 — are good benchmarks to begin comparing the overall design traits of the AC75.

Weight, Stability and Power

When looking at a boat’s performance potential, designers and engineers must explore the big three: weight, stability and power. When comparing the sail plans (Figure 4), the lower rig height of the AC75 is the first obvious difference. The AC75 will weigh slightly more than the AC72, and twice as much as the AC50, which means it will struggle in light winds and down-speed maneuvering. With less drag on the sail plan and foils, however, the AC75 should be strong once it’s up and going in strong winds.

Catamarans have inherent zero-degree stability, with low wetted surface and light displacement. They can afford to have more power in the sail plan in order to fly the windward hull, then quickly pop up on the foils. In contrast, the AC75 monohull is wide, which introduces a lot of wetted hull surface and a very low righting moment in displacement mode. An International Moth uses a narrow hull to address the wetted-surface problem, and the crew’s weight on the tramp contributes to its righting moment. A Moth, however, is difficult to sail at low speeds and is prone to capsize. The AC75, being a much larger boat, requires a wider hull for stability and to create a wide enough platform to get the port and starboard foils apart. The power-to-weight ratios of the AC75 when it’s not flying versus flying gives an indication that the transition crossover may be more challenging than it was with the catamarans.

The Hull Truth

The AC75’s hull shape is “open,” but there are a number of tight constraints, such as length, which is 20.65 meters (67.7 feet), plus or minus 50 millimeters. The bow’s fullness is limited by two maximum-beam measurements within 4 meters of the bow, presumably to avoid scow-type hull shapes. There is also a minimum bow volume of 40 cubic meters, in consideration of pitch-pole prevention, which the shorter rig will also help with. The cant and axis of rotation of the side foils is fixed at 4.1 meters apart, which will ultimately influence waterline beam. Maximum beam is set with a tight tolerance of 4.8 to 5 meters, and minimum beam at the transom must be 4 meters.

Design teams will spend a lot of time exploring hull shapes within the above limits, looking for a shape with minimal drag in light-wind displacement mode while also addressing the stability required to generate thrust for takeoff. Windspeed limits and the expected wind conditions at the venue will be a hot topic because they can influence the overall design package. Crews were comfortably foil-tacking the AC50s down into the 8- to 9-knot true windspeed zone. It will be interesting to see where that zone ends up with the AC75.

The hull has no significant limits on structure other than intermediate carbon-fiber modulus and a handful of standard AC rule limits. Some level of recycled materials must be used in the construction, which is a refreshing direction for the America’s Cup. Teams are allowed to build two hulls, with the earliest launch dates of April 2019 for Boat No. 1 and February 2020 for Boat No. 2.

The Shape of Foils to Come

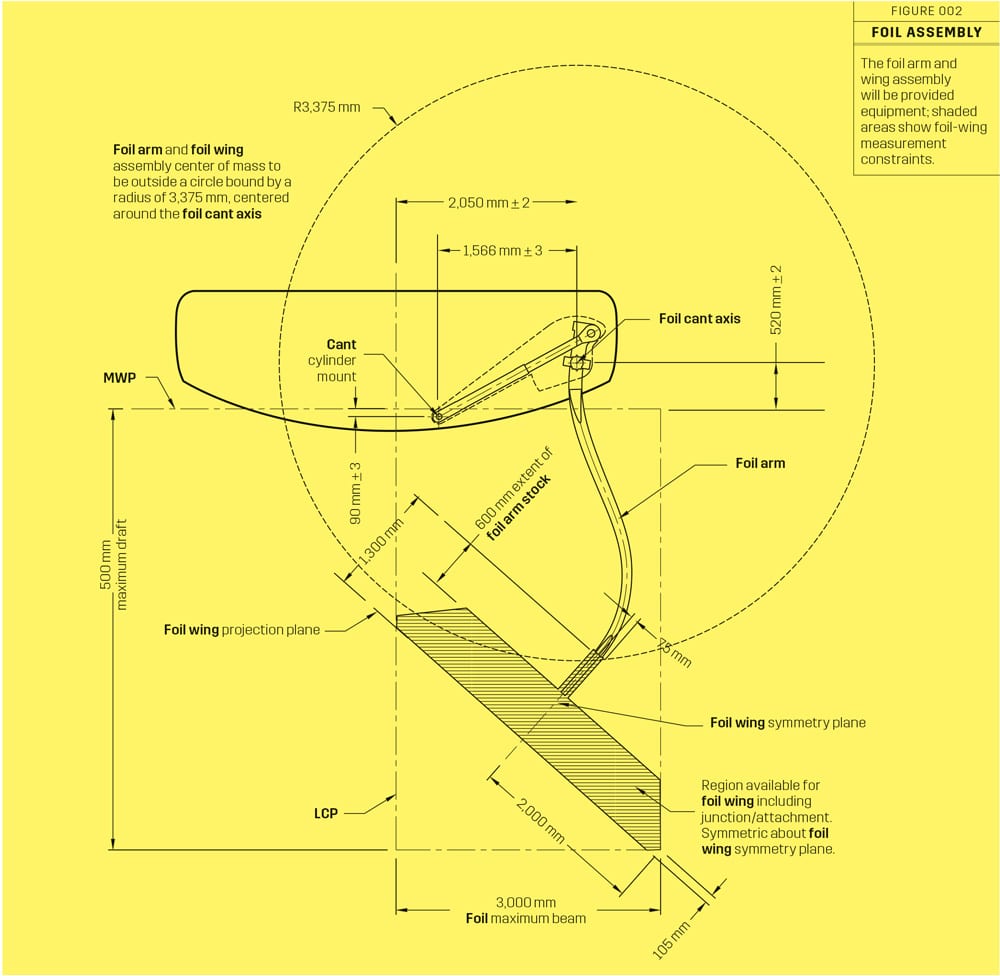

The AC75’s port and starboard foils are composed of a foil arm, a foil wing and a flap attached to the foil wing. The foil arm will be supplied equipment (limited to four). The foil wings and wing flaps are open to design but must fit within defined parameters. Teams are restricted to building six foil wings and 20 foil flaps. Wings and flaps can also be modified up to 20 percent of their weight. Each foil assembly has a prescribed weight of 1,175 kilograms that it must hit within 1 percent, and a center of gravity that is required to be close to the foil wing for an overall minimum stability. To avoid excess volume in the foils, steel will likely be the material of choice for the lower portion and wing. It’s interesting to note that the two foils contribute 40 percent of the boat’s overall weight. Remaining weight considerations for boat structures, systems and deck equipment will be ongoing to ensure the boat stays on weight.

The T-foils will require extensive design and engineering research, much like they did with the AC50s. Maneuvering capabilities will heavily influence the optimization process. Foil-wing areas will be generally reduced to the bare minimum for steady-state straight-line sailing. Expect two to three different foil wingspans and then some variations in the flaps to suit conditions. Flap lengths are limited to 50 percent of the total chord of the wing‑flap combination.

The main foils can only rotate on one forward/aft cant axis. Instead of pulling a foil up and down through a bearing case when tacking and jibing, as it was with the cats, the foils on the AC75 will rotate up and out of the water. In many ways, this is a much simpler system than those used on the AC50s and AC72s. Additionally, the AC50 and AC72 rotated the entire foil to change the lift of the main foil, whereas the AC75 has only the flap rotating, like the flap on a Moth. The Moth uses a wand mechanism to provide automatic control of the flap, but with the AC75, the crew will need to manually operate the flap.

The L-shaped foils of the last two Cups are gone, replaced by the AC75’s T-style foils. Much time and money were spent in the last Cup analyzing dynamic foil stability versus performance. The V-shaped foil orientation used on foiling catamarans like the GC32 provides stable flight with minimal adjustment, but at the expense of hydrodynamic drag. The T-foils of the AC75 class can be oriented to provide both lift and side force to minimize the induced drag (drag due to lift), which allows more speed potential, provided the crew and control systems can handle the loss in dynamic stability.

Only a single rudder and rudder wing is allowed. When foiling, the rudder and the main foil work together to lift the boat out of the water. Having the rudder on centerline does rob some righting moment from the boat because it is offset to windward of the main foil by roughly 5 meters. Ideally, one would position the foils on the boat so the rudder takes very little lift. However, the rule imposes limits on the center-of-gravity location and limits on the primary foil location. As a result, teams will have a tendency to: a) place the rudder as far back in the boat as possible; b) push the boat’s center of gravity to the rule’s forward-most limit with deck systems and components; c) push the main foil against the aft limit. All of this is intended to limit lift on the rudder wing, or in other words, try to centralize the boat weight onto the main foil, which is much farther to leeward.

Rudder lift will be adjusted by rotating the entire rudder assembly about the lower bearing, similar to the AC50s, and will be actively controlled during maneuvers to keep the boat level and maybe also make active adjustments while straight‑line sailing.

Power in the Sail Plan

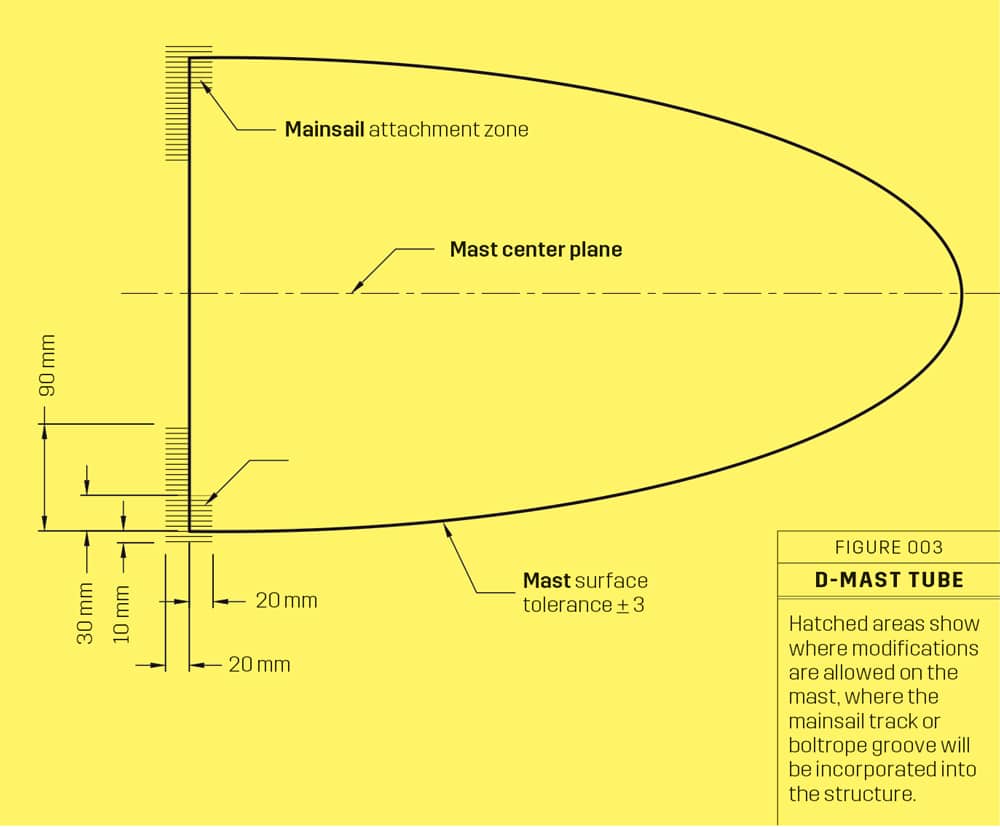

Sails return after taking a back seat to the rigid multi-element wings of the past seven years. The AC75 Rule provides a framework for a double-surface mainsail and a permitted control system, and control areas at the top and bottom of the mast (Figure 3) that permit greater shape control than a normal mainsail. The mainsail area is limited to a minimum and maximum, within 7 percent. The mast is a large one-design “D section,” similar to the AC50 wing, and it will serve as the leading edge of the mainsail and structural tube. The mast will pivot on a ball that also transmits compression load from all of the support rigging, all of which will be supplied to the teams. The hatched area in Figure 3 shows the only area allowed for modification on the mast where the mainsail track or boltrope groove will be incorporated into the structure.

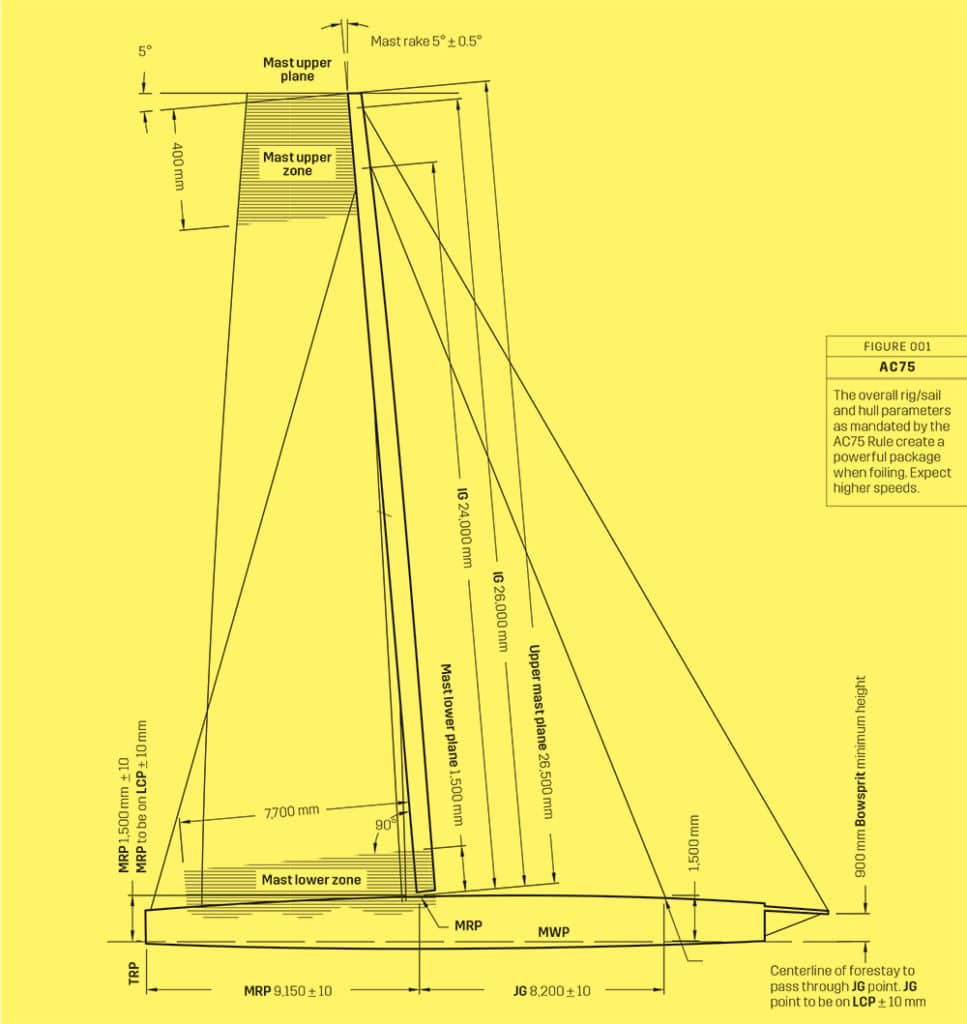

Headsails are fairly standard, with their profiles governed by leech perpendiculars and girth limits. Small, medium and large code-zero-style headsails are allowed within these limits and will be chosen based on the day’s sailing conditions, upwind and downwind. If foiling conditions exist, I suspect there will be one headsail choice for the race. Figure 1 shows the restricted positioning of the mast and tack positions of all of the headsails, effectively placing the rig and sails in the boat at a specific location. Self-tacking jibs, interestingly enough, are not allowed, presumably under the guise of not allowing an automatic system, but it will also give the crew something to do.

Control and Foil-Canting Systems

As with the previous two Cup cycles, the speed and accuracy required to adjust submerged foils will have a huge impact on overall boat performance. The ability to sail the boat consistently at the apex of controllable flight could be one of the difference makers. The hardware and software required for such precise flight, therefore, will be one of the focal points of the development teams. The AC75 Class Rule specifically allows battery power for the adjustment of all underwater appendages (except steering), completely relieving the crew from producing the power to achieve movement, but still requiring manual input from the crew to control the angle of the foils. The system to control and change the cant of the main foils to put the foils in and out of the water will be supplied equipment that cannot be modified, so the speed and power to move these will be the same for all of the teams.

All sails, mast controls, halyards, etc., can only be adjusted using direct crew energy. Unlike the rigid-wing sails of Cups past, the mainsail will require significant leech tension to hold shape. This is a big difference compared to the AC50 and AC72 wings, which could be adjusted both in twist and overall angle with much less load and energy. Fast adjustment with wings is much easier, giving more heel control with less energy required. Trimming through twist alone might not be as easy as it was with the AC50s. Therefore, we could see vang sheeting or highly efficient low-friction traveler cars for fast heel control as a focus for development, along with top mainsail twist control, which has a very open design space in the top 4 meters of the mast and sail.

Power to the Crew

Until the previous Cup and 2010’s Deed of Gift match between Oracle Team USA and Alinghi, stored energy, or energy on demand, wasn’t allowed. In the IACC Class (1990 to 2007), more than half the 17-person crew were dedicated strictly to power production (grinders) to facilitate efficient tacks, jibes, sail hoisting and retrieving. In 2013, we saw the racecourses shortened and the crew reduced to 11. Once foiling was introduced, extreme fitness was required because eight of 11 sailors were grinding almost all the way around the race track to supply power demands and keep the boat operating at peak performance. In the 2017 Cup in Bermuda, the AC50 further reduced the crew to six sailors and shortened the course yet again. Accumulator tanks were allowed to buffer energy produced by the limited crew so it could be used whenever required. The AC75 Rule has an 11-crew limit, but again, a significant portion of the crew will be dedicated to energy production that three or four primary sailors will produce.

Traditionally, large boats require large crew numbers to handle and change a number of sails to get the boat around the race track. These foiling boats, however, are different animals in that apparent-wind angles and apparent-windspeeds hardly change between sailing upwind and downwind, which is why changing sails is less common for this high-performance breed. Traditional spinnakers and gennakers that require technique and many hands have no place on a foiling sailboat.