The rocky coast of Brittany, France, is breathtakingly beautiful but melancholy in winter, when the days are short and sunlight sparse. Yet, as the giant blue-and-white trimaran Macif sails into Brest in late December, a ray of sunshine pierces the clouds, turning the dull North Atlantic an electric blue. A burst of collective optimism, often in short supply in this corner of the world, is palpable as the craft’s young skipper thrusts his arms skyward in celebration. Cheers and shouts from hundreds of spectators that have arrived hours before sunrise are audible from far out across the water. Dozens of yachts position themselves for a closer glimpse of the lone 34-year-old Frenchman who has shattered the nonstop around-the-world solo record. The clock stops at 42 days, 16 hours, 40 minutes and 35 seconds, and Francois Gabart’s cheerful and stoic demeanor collapses in a gush of tears. “This welcome really caught me by surprise,” he says later. “It was the one thing I hadn’t prepared for.”

For many observers on this day, a mere glimpse from afar of the man who is definitively the greatest offshore sailor of a generation is worth the trip. The French have never put a man on the moon, but their reverence for offshore sailors is on par with their worship of their musicians, celebrity actors and even astronauts. Gabart’s boyish charisma adds to his appeal, and his popularity has only grown since winning the Vendée Globe in 2013, and then the Route du Rhum trans-Atlantic race in 2014.

“What he did is insane,” says Fanny Mayer, who drove to Brest from the other end of Brittany, with her husband and four kids. “We wanted to see the man in person.”

Gabart’s record follows the achievements of countrymen Francis Joyon, who (with IDEC) lowered the outright record to 40 days in February 2017, and Thomas Coville, who held the singlehanded circumnavigation record before Gabart’s arrival on December 17, 2018. To put Gabart’s feat in perspective, consider this: He shaved seven days off Coville’s record and was within striking distance of the 40-day fully crewed target.

Macif is 30 meters long and 21 meters wide at its maximum beam. Its sheer scale and complexity make for an altogether different offshore experience than that of the fastest foil-assisted offshore monohulls. The most apparent distinction is, of course, the deliverance of high average speeds. Macif is capable of sustaining 35 to 40 knots over hundreds of miles, and the use of foils certainly helps in relatively light winds of 18 or 19 knots, allowing the boat to swiftly pass through the course’s traditional light-air zones.

Macif‘s design began more than four years ago, at a time in which the America’s Cup boats began to adopt L-shaped foils. The team astutely studied how the foils react under immense dynamic loads. “Just knowing how the foils react when under massive load has already made a huge difference,” says Antoine Gautier, Macif‘s head engineer. “What we are learning now will also help us to design our next-generation foils, which will be a lot bigger.”

As Macif foiled around the world, easily exceeding 30 knots at times, Gabart says he was surprised by how smooth the boat sailed as it hovered 50 centimeters above the water. “It is amazing how stable the boat is when it is flying,” says Gabart. “There was hardly any heel. Compared to how you are close to broaching when the heel is 12 or 14 degrees, it certainly feels good.”

Even while flying at 30- to 40-knot speeds, Gabart never had to touch the helm to steer. Instead, he relied on autopilots and remote controls to make small adjustments to the sail trim and angle. He remained largely protected from the elements, operating from the boat’s command center alongside his bunk.

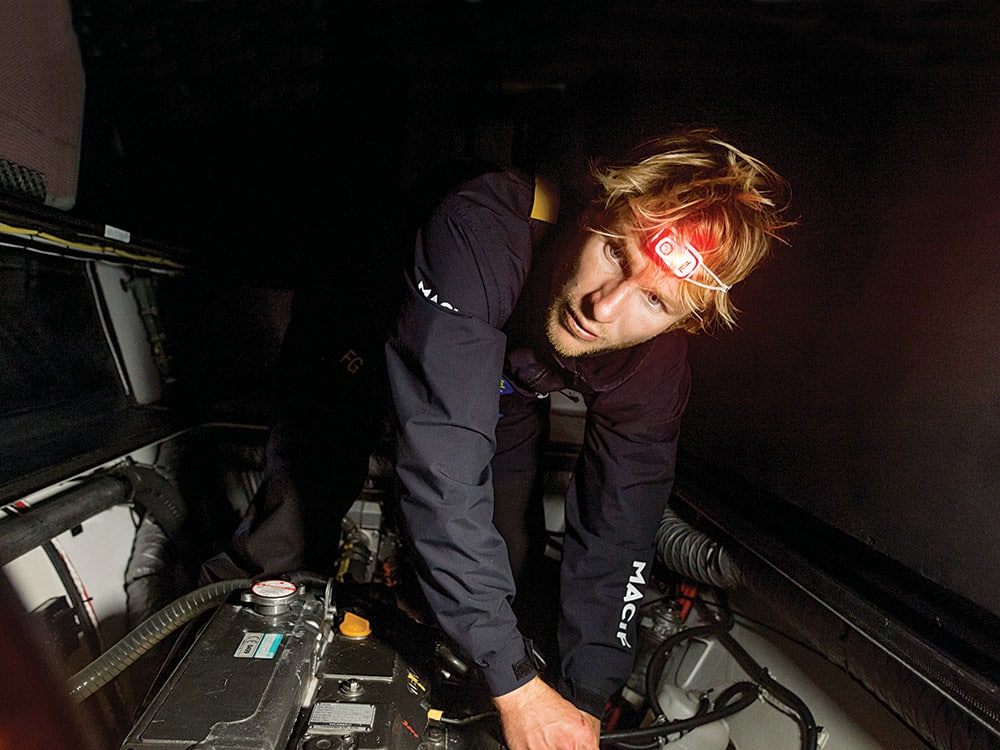

Solo sailors are no longer truly alone these days. Even in the most remote areas of the Southern Ocean, Gabart’s experience was often broadcast on Macif‘s website and on the French insurance company’s Facebook and Twitter feeds. His support team back in France could watch live video of what the boat was doing, and troubleshoot breakages and sea conditions. Macif‘s lead engineer Antoine Gautier communicated regularly with Gabart by chat applications, such as Skype, which he says is more efficient than voice and video calls. After analyzing boat damage by video, Gautier would send text and image files for Gabart to download as a reference.

Constant multimedia broadcasts and smiling selfies certainly didn’t detract from the skipper’s performance, but Gabart’s sharing of his emotional highs and lows in almost real time made the passage richer for all who followed.

“I felt that sharing photos and videos of what I experienced gave an additional layer of meaning to what I was doing, which was already fantastic,” says Gabart. “It’s also a way for others to come closer to living what I’m going through, without taking the risk.”

Gabart, however, had limited bandwidth to devote to social media. Most of his time was consumed with making repairs, using power tools to craft custom parts from carbon sheets that he would then epoxy-glue to broken gear. On-the-fly repairs is something he had prepared for as he familiarized himself with every inch of the boat while it was being built.

Even while flying at 30- to 40-knot speeds, Gabart never had to touch the helm to steer. Instead, he relied on autopilots and remote controls to make small adjustments to the sail trim and angle.

As the “whatever can go wrong, will go wrong” axiom usually rings true, Gabart was faced with the unexpected in the Southern Hemisphere: a broken batten, which had become jagged and was cutting into the mainsail.

“Breakages happened that are totally unforeseen,” says Gabart, laughing. “I’ve been sailing offshore now for over 10 years, and that was the first time I had to fix a batten. But by having prepared to fix anything that can conceivably go wrong ahead of time, you’re ready when the unexpected happens.”

The boat’s efficiency and Gabart’s seamanship skills aside, he is the first to admit he owes much of his record to luck. This was especially true in the beginning stage of the record attempt. Once the team identified a departure window, the green light was given to assemble at the official starting point at the Ile of Ushant near Brest. The long-term routing appeared favorable, but Gabart was prepared to stop and turn back if the weather proved to be less than ideal at the equator. He would have considered it a dry run and then waited to begin again, says the team’s onshore router, Jean-Yves Bernot.

“These records are broken in the South Atlantic,” says Bernot. “It’s a rolling process, and accuracy is limited. If the conditions were not what we wanted, we would have told Francois to stop and come back.”

Turning back was indeed a consideration when Gabart fell behind Coville’s six-day sprint to the equator.

“At the start of the trip, I was focusing on making sure everything was functioning OK, and not much else,” says Gabart. “It took a few days before my hypervigilance gave way to my becoming more conformable with the boat, and I was able to begin making more repairs.”

In huge waves and strong winds gusting more than 50 knots near Argentina, and at one point, Macif logged a speed burst to 45 knots while surfing down a wave, posing a major risk of destroying the boat.

After reaching the equator with a relatively slow passage, Gabart then blasted through the South Atlantic to reach the Indian Ocean 12 days after his departure. The sprint put him more than two days ahead of Coville’s time. During this stretch, Gabart also broke his own record, covering 851 nautical miles in 24 hours — at an average speed in excess of 35 knots.

As he began to feel more comfortable with the boat, everything then came together. The wind was at the boat’s sweet spot of 110 to 120 degrees true, pushing against a reefed mainsail.

“This was the first truly magical moment,” says Gabart. “Everything was just right then, although I knew I would be in store for some rough patches ahead.”

He didn’t have to wait long for trouble to rear its head, however, and he hit his first snag in the Indian Ocean, hemorrhaging more than a day of his lead. He had to repair a gennaker furler and experienced generator troubles that could have resulted in a total electrical failure in the middle of the Indian Ocean. His onshore crew pinpointed the source of the short circuit, averting a crisis.

Gabart was then forced to plunge south to connect with his next weather system, which put him south of the Kerguelen Islands and into the nerve-racking iceberg zone. The low also proved to be too much to handle. With the low came 40 knots of wind and 20-foot waves that pounded Macif. Gabart appeared visibly nervous in a video he shared from his roller-coaster ride inside the cockpit. Through his window, he showed Macif‘s hulls pounding over and through the waves.

“It’s pretty crazy out there from what I can see,” said Gabart, “but the boat seems to be holding up, and we’re still making progress.”

After passing the southern tip of Australia, Gabart met more-severe weather and sea conditions, forcing him to slow to a comparatively benign 25 knots until reaching the halfway point in the Pacific.

Heading south once again to catch another low near the same longitude as New Zealand, Macif‘s radar system failed to detect an iceberg dangerously close to Macif‘s path. After completing a jibe, Gabart spotted a roughly 300-meter block of ice floating within eyesight.

“It was beautiful to look at,” he says. “But that was when I was really scared, because all it took was a small piece of submerged ice to destroy the boat. I could only hold on and hope for the best.”

His magical sailing resumed after the iceberg scare, with relatively few repairs to make as he made headway by consistently maintaining 30 to 45 knots of speed in 35 knots of wind in favorable conditions. After a rough yet relatively uneventful rounding of Cape Horn, Gabart finally admitted to feeling the effects of his relentless pursuit. “The boat is taking a lot of punishment,” he confessed, “and so is my body.”

He struggled to maintain control of the boat in huge waves and strong winds gusting more than 50 knots near Argentina, and at one point, Macif logged a speed burst to 45 knots while surfing down a wave, posing a major risk of destroying the boat. It was then that a gennaker furler broke again, at one of the worst possible moments.

“I would work on making the repair for three seconds, and then hold on when going over a wave, and then going back to work for three seconds,” says Gabart.

But Macif began to pick up speed again after piloting through the Doldrums. Positioned between the Azores and the finish line at Ushant, he described — during a satellite phone call — the culmination of his mental and physical toll of spending over a month hardly sleeping, always ready to press the panic button on the autopilot should one freak wind gust send Macif tumbling and crashing.

“I’m trying not to think too much about the record,” he said. “My only goal is to focus on what I have to do. I’m taking it day by day and hour by hour. I’m very tired, and I don’t have very much more energy. I’m just trying to focus my energy on positive things.”

Gabart’s exhaustion gave way to euphoria as he sailed into the Bay of Brest, to where hundreds of spectators arrived to greet him. Broadcast live on national TV and radio, Gabart cheerfully gave a series of live interviews, captivating an entire country. Later, as he made his way through the cheering crowds, Gabart embraced the moment with his signature beaming smile, savoring his accomplishment, if only for the moment.

Once acclimated to life ashore again, he was already thinking ahead — to racing not the clock but against a fleet of flying Ultime Class giants when the first around-the-world Ultime Class solo race starts in 2019. Indeed, this era of offshore foiling is only just beginning, says Gabart, and while his record is encouraging, it represents a new challenge. His official record (as ratified by the World Speed Sailing Record Council) stands at 21,600 nautical miles sailed at an average of 21.08 knots. The actual distance sailed, however, was 27,589.7 nautical miles at an average of 27.2 knots. Gabart he knows there’s plenty of room to make these foiling boats even faster than they already are, but the benchmark is firmly set.