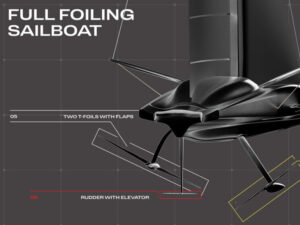

With the 37th America’s Cup using the AC75 class rule for this second generation of high-tech foilers, all but one of five teams—newcomer Alinghi Red Bull Racing—have the design jump-start of servers full of historical data and real experience with the 75-footer from the last go. It was, therefore, no surprise when the Protocol sought to level the playing field and reduce costs by allowing one prototype per team in the lead up to building their one and only new-generation AC75.

Teams are also required to buy a one-design AC40, which could be used as a prototype to design, test and troubleshoot mechatronic systems and foils. They could also leave the AC40 in its one-design configuration and instead design and build what’s called an LEQ12, which means “less than or equal to 12 meters.” Each team has chosen a different path, and only the outcome of the Cup itself in late 2024 will tell which was the right one.

Defender Emirates Team New Zealand chose to use its in-house-designed AC40 as a development platform, as will Alinghi Red Bull Racing (in addition to training on the former AC75 of Emirates Team New Zealand) and American Magic, which has reportedly purchased two of the 40s, but INEOS Britannia and Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli have struck out on their own with custom-built LEQ12s, each notably different in many ways. Luna Rossa’s LEQ, with a radical graphics wrap either intended to distract the eye or maintain an Italian flair, is said to mirror the AC75 of Emirates Team New Zealand from the last Cup. INEOS Britannia’s T6, on the other hand, is an unworldly shape that can only be properly “sailed” when on its foils.

Luna Rossa was first to launch its LEQ12, at its base in Cagliari, Italy, in October, and thus was first to undergo tow testing to ensure the reliability of its sophisticated electronic foil and hydraulic-control systems. But days later, the rig and sails were on the boat and it was flying. The red-and-black-checkered specimen was described by observers as skittish at times but fast, and the sailors, seated in opposite cockpits, were promptly foiling through maneuvers until their first capsize brought their session to a halt.

Co-skipper Jimmy Spithill, the master of spin, shrugged off the capsize as no big deal. “Capsizes happen when you get caught slow,” he said to America’s Cup Recon afterward. “We just got caught downspeed.”

Indeed, the boat was righted and sailing again the next day, but ultimately, the purpose of the prototype is less about boathandling practice for the sailing team than it is data collection for those crunching numbers back at the base. There are said to be roughly 14 departments between the design and build teams, led by veteran Cup sailor Horacio Carabelli, who says the LEQ12 is “the most important tool we have, and the only tool the rule allows you to have.”

Rather than going down a somewhat predetermined development path with the AC40, or even sailing their previous AC75, as American Magic has been doing for months in Pensacola, Florida, the Italian and British challengers rationalized a custom LEQ12 gives them greater latitude by starting with a clean sheet to develop their own systems and “play with what you have,” Carabelli says. “It’s important to design your own boat because you can control what you are doing. In the background, we have what we learned from the last Cup and wanted to implement that into the prototype.”

For INEOS Britannia, starting with a prototype was a natural way to flex the muscle of their partnership with Mercedes Formula 1. “This is the start of a long journey of testing,” said skipper Ben Ainslie at the boat’s commissioning in November.

What does the unique design of T6 say about the team’s AC75 design to come? “Absolutely nothing,” Ainslie says. “It’s a test boat. It’s not built or designed to be the fastest 40-foot foiling monohull around. It will give us valuable insight into our performance tools and help us validate those tools. We were strong on the LEQ12 option because we wanted to optimize the design, and build the hull and the components that go with it. This is the first true boat that Mercedes could say they designed and built.”

Observers and the America’s Cup Recon Unit assigned to the team immediately seized upon protuberances on the front of the foil bulbs as something of interest, about which Ainslie confirmed are simply sensors that “will give us much more accurate data in terms of what’s going on under the water with the foils. It’s an incredibly well-sensored boat.”

The Italian and British challengers rationalized a custom LEQ12 gives them greater latitude by starting with a clean sheet to develop their own systems.

Sensors and proprietary simulators, which are now heavily used and enhanced with artificial intelligence, are pay dirt in these early stages, painting a critical picture of the engineering complexities of the mechatronics, structures, sail designs and foils, all of which ultimately feeds into the boatbuilding, where reliability is paramount. Emirates Team New Zealand demonstrated the importance of this in late October when it crashed its AC40-turned-LEQ12 in a high-speed pitchpole and brought its testing to a screeching halt.

“The structural part is very important,” Carabelli says. “The AC75s are a very light boat with a fair amount of loads in some areas. You need a boat that meets [the rule’s] displacement limits, which is not an easy task.”

While making good use of its LEQ12, Luna Rossa eventually suffered its own setback when the team damaged its mast in early November while the boat was being prepped for launch. The accident wiped away nearly three weeks of sailing. But by late November, they were back on the water and pushing their LEQ12 hard once again, rotating sailors through the boat and validating modifications that were fast-tracked during the mast repair, another clear benefit of dealing with a LEQ12 versus an AC75.

“It’s easier to deal with,” Carabelli says. “If you want to implement a new system, it’s easier because it’s not as complicated; we’re quite flexible to do modifications, and not a single day goes by where we don’t change a small detail.”

Meanwhile, over in Palma, Spain, where the INEOS Britannia squad set up its winter base, the sailing team was taking its time before going full-package, instead focusing on tow testing without the rig, beaming data straight back to engineers at Mercedes F1 headquarters in England.

“There are a lot of areas to check,” Giles Scott told America’s Cup Recon after the team’s first joyride, “a lot of debugging with hydraulic and electronic systems. The tow testing is a focal part of the early session with T6; the designers want nice steady data.”

In the modern America’s Cup era, there’s no denying data is gold, and mining for it requires chipping away at everything else. The LEQ12 is simply a cart sent down the shaft to find the mother lode.