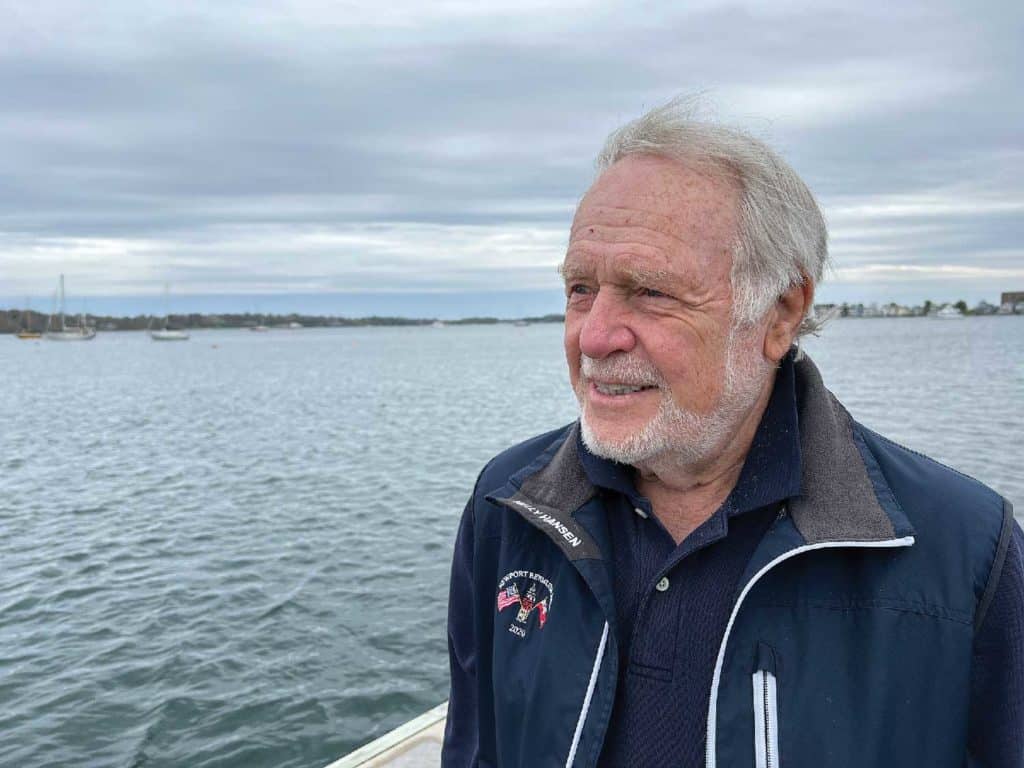

For Bob Morton, a seasoned racing sailor based in Newport, Rhode Island, who has owned more yachts named Brigadoon than you have toes on your feet, there’s one definitive moment in time that crystallized and confirmed everything he knew and loved about offshore competition with a crew of trusted mates in brisk winds and deep-blue water. That moment is the third afternoon of the 1982 Newport Bermuda Race aboard his Sparkman & Stephens-designed 56-foot Brigadoon III.

“It just all came together,” he says. “Just a beautiful sunny day. Whitecaps on every wave. Reaching along just great. The boat in perfect sync and trim.”

And that single passage of time and miles was affirmed in unforgettable style several hours later when Brigadoon III charged across the finish line as the ’82 race’s overall victor and winner of the St. David’s Lighthouse Trophy, joining a select, elite club at the pinnacle of the sport. “You knew your life was going to be different if you won the Bermuda Race,” Morton tells me, some 40 years after the fact, with a faraway gaze that suggests he recalls it as if it were yesterday. “And it really did change things, you know?”

Though 1982 was the year everything fell into place, Morton has a rich personal history with the Newport Bermuda contest, having served as skipper, navigator or watch captain on no fewer than 19 editions of the event. To grasp his accomplishments as a whole, it’s instructive to start at the beginning (which he’s summarized in his self-published book titled, yes, Brigadoon III and One Moment in Time).

The son of an engineer at John Hopkins University who led the development of the Polaris missile program, the Morton family spent summers in Little Compton, Rhode Island, where Bob started sailing in the waters off Sakonnet Point, first in a little skiff that came with the house, and later in a Beetle Cat that washed up in the yard during Hurricane Carol. To say he had an affinity for the water would be an understatement; from those early days skimming the harbor, he went on to join the sailing team at the University of Rhode Island (where he also earned a degree in oceanography), the highlights of which were a podium finish in the collegiate nationals and outright victory in the New England championships, both in his junior year.

But for Morton, Sakonnet Harbor was more than a place where he served his apprenticeship under sail. It was also where he and his dad, also named Robert, fell in love with what was “by far the most beautiful boat in the harbor,” a blue Luders 48 sloop. Originally named Storm, the boat was now called Brigadoon after a mythical Scottish town, which also reflected the Morton clan’s Scottish roots.

While the name was ideal (and became a family tradition), as an ocean racer, that inaugural Brigadoon ultimately was not; although, it proved to be a serviceable entrée to all the namesakes that would follow.

For four years starting in 1964, soon after Morton’s graduation from URI, the Mortons campaigned Brigadoon hard and well, winning the Narragansett Bay Championship in 1965 and making annual runs to Annapolis, Maryland, to compete on Chesapeake Bay. It was right after the start of the 1967 Annapolis to Newport race that the mast broke, which provided the opportunity to swap out the less-than-optimal fractional rig for a masthead setup. It was a significant upgrade that, unfortunately, was a tad too mighty for the boat’s stressed wooden frames. This led to Brigadoon II, a Columbia 50 with an overlapping 180 percent jib that was killer in light air but got hammered by its unfavorable rating in the heavy offshore stuff. It was frustrating enough that they soon said sayonara to Brigadoon II.

It’s been said the third time is the charm, and so it was with Brigadoon III.

Originally called Equation and built in California for a vastly experienced New York YC stalwart named Jack Potter, it was the first ocean racer designed by Olin Stephens after his radical 12-Meter Intrepid. Like the 1968 America’s Cup winner, the S&S 56 sported a separated keel and skeg-mounted rudder. Also built in ’68, Equation was the forerunner of a slew of ’70s-era slayers, including Running Tide, Yankee Girl, Charisma, Palawan and many others.

“She was so much faster than anything else that was around at the time,” Morton says. “I don’t think people realized what a quantum leap that was with yacht design.”

In 1971, Equation became the Mortons’ boat, and the name on the transom was swapped to Brigadoon III, which set the stage for their first Newport Bermuda campaign in 1972.

Fifty years later, it’s almost impossible to fathom how far and fast ocean racing has evolved over the years. Satnav? Navigation was strictly by dead reckoning or sextant, and the latter was pretty useless when the weather filled in on day two, which it always did. Gulf Stream charts? Forget it. Plunk a surface-temperature thermometer over the side and hope for the best. Some said you could tell if the current was with or against you by rising or falling water temperatures. But who the hell knew for sure?

Aboard Brigadoon III, roughly midway down the track, the wispy cirrus “mares’ tails” clouds overhead were the first sign it might get blowy, and they ended up beating into a small hurricane of 50-plus-knot winds on the final approach to Bermuda, upon which they luckily got a bearing by homing into the signal of the island’s sole, yep, country-western radio station. But they made it safe and sound, notching fourth in class and eighth overall.

(Jack Potter, on his new Equation in that same ’72 contest, flipped on his loran-C in the latter stages to avoid plowing into Bermuda’s adjoining reef and was unceremoniously disqualified; although, it led to a rule change allowing the navigation aid in subsequent races. And later that year, during the SORC’s Miami-Nassau Race, thanks to Robert Morton’s John Hopkins connections, Brigadoon III became the first yacht to ever employ satellite navigation in an ocean race, powered by “a receiver the size of a suitcase, and a Wang calculator that was nearly as big.”)

Then, a year later, when Morton’s dad, Robert, fell ill with a mysterious, impossible-to-diagnose ailment—it was seriously touch-and-go for a spell—Brigadoon III was sold, the program seemingly over and done. But it turned out not to be a permanent hiatus. Robert recovered (he later didn’t remember the boat had changed hands while he was delirious in the hospital), and the boat was again up for sale a decade later.

Coincidentally, Morton had just retired from his oceanographer position working for the US Navy and was about to begin a new career with a company called Science Applications (later SAIC, which played a prominent role in future America’s Cup campaigns), where he opened the Newport office. With a $100,000 windfall after cashing in his Navy retirement account, he plunked down the dough to reacquire Brigadoon III. (If I’d only bought SAIC stock, he sometimes thinks, with 10-figure dollar signs dancing in his head.)

No matter, he was about to accrue memories money simply can’t buy; indeed, he got the boat just in time for the 1982 Newport Bermuda Race.

He had some serious characters (and sailors) on board: His watch captains were fellow Newport Yacht Club fanatic George Kirk and a very amusing and talented Australian called Geoff Ewenson (the father of another great sailor by the same name), who’d sailed into town on a delivery, married a local gal and never left.

They nailed the start in a classic Newport southwesterly sea breeze, the first inkling the race would be special (and, although they didn’t know it yet, the opening salvo in their wire-to-wire victory). The next key move was on the afternoon of the second day as they approached the Gulf Stream; a decade after the ’72 race, there was plenty more information, and they were more or less aiming for the waypoints of a predicted meander. However, they’d been consistently headed on the approach, to the point they were on a course parallel to the Stream but more or less still laying Bermuda.

To tack or not to tack? (Plenty of boats were basically sailing a rhumb-line course to the island and opted not to.) That was the question, and a lively discussion ensued. That is when Morton said to throw one in. “To me, getting in the Stream [as soon as possible] was the right thing to do,” he says. “The boat just ahead of us, a more modern S&S design called Siren, owed us a lot of time. And we beat her in by a lot.”

Morton contends the Bermuda Race is actually three races: Newport to the Gulf Stream, across the Stream, then the final run to the island. Brigadoon III was in the process of acing the first two tests—and was about to crush the third.

It was a rough, stormy Gulf Stream crossing, from which they emerged under a deeply reefed main and blast reacher at dawn on the third day. As the morning wore on, it was apparent a Swan 60 called Gone with the Wind—which owed them a ton of time—was chasing Brigadoon III down from astern. That is when Kirk, in his perfect Rhode Island accent, loudly announced, “Storm’s ova. Let’s go to the big jib!”

“That was the second big call of the race,” Morton says. Checkmate.

Fifty miles out, they learned the fleet’s scratch boat, Nirvana, which owed them a good 12 hours, had not yet finished. Morton’s friend Mike Keyworth was Nirvana’s sailing master, and the big maxi was in the midst of a record-setting pace of just over two days, 14 hours that would stand for the next 14 years.

Along with Kirk’s “Storm’s ova,” which would become a cherished rallying cry going forward, yet another Brigadoon tradition started soon after the finish: Ewenson’s batch of “Loudmouth Stew,” a concoction of whatever fruit juice was handy and plenty of rum. But the real party happened a night later, when victory was confirmed and the crew took over the Hog Penny Pub, with Ewenson on stage leading the whole bar in renditions of Aussie standards “Waltzing Matilda” and “The Wild Colonial Boy.” He was all that and more.

Other Bermuda races followed, many more on a series of Brigadoon boats, as well as other rides aboard a series of designs from Frers, Tripp, McCurdy & Rhodes and others, a veritable who’s who of ocean-racing luminaries. And while Morton enjoyed a class victory here and there, never again did he win the overall prize. But that’s OK; he’s had his taste and crossed it off the bucket list.

Sadly, neither Kirk nor Ewenson is still with us. But it speaks to Morton’s statement that winning the Bermuda Race would be “life-changing” in that both their obituaries prominently mentioned that immortal run on Brigadoon III in the summary of their major life accomplishments. For Morton, his watch captains, and everyone else aboard Brigadoon on that sparkling summer afternoon charging into Bermuda in June 1982, it was a moment shared together, then frozen in time. It was certainly one of the best, most lasting of their lives.