FBJohn368

The tone of the seven-month-old competition for who gains the initiative in the next America’s Cup was brilliantly summarized five minutes into the oral arguments in New York State Supreme Court on January 23. Justice Herman Cahn, who has been trying to get the two parties to settle for months, interrupted Barry Ostrager, the new lawyer for Alinghi and Societe Nautique de Geneve, and asked a question: “Have the two sides had any conversations since our last hearing?” Ostrager replied, “No, your honor. There are irreconcilable differences.”

That much was obvious from the presentations by the two sides. In increasingly tense body language and bitter spoken language, each accused the other of misrepresenting or selectively interpreting the America’s Cup rules and the facts of the case. Whatever Ostrager said for Alinghi, Ernesto Bertarelli’s America’s Cup defender, was contradicted by James Kearney, representing the Golden Gate Yacht Club of San Francisco, which has challenged for Larry Ellison’s BMW Oracle Racing.

Here is the background: In November, Justice Cahn threw out Alinghi’s choice as the challenger of record, the Spanish Club Nautico Español de Vela, and replaced it with Golden Gate. The stated reason was that this small, hastily created club had not observed a basic requirement laid down in the America’s Cup’s rules, the Deed of Gift, by not running an annual regatta (the reasonable idea being that this is a fair test of a club’s seriousness and experience). This failure to follow a clear rule was Golden Gate/Oracle’s tiny opening, and behind it lay a strong feeling among all the challengers, most observers, and eventually the court itself that the selection of this club to represent all the challengers in the writing of the rules for the next Cup races was just one piece of evidence of self-dealing by SNG as it sought to put a hammerlock on the event. SNG is now trying to convince Cahn that he made a mistake in naming Golden Gate as challenger of record.

If you are (reasonably) wondering what all these law suits have to do with sailing, let me pause for a moment to offer an analogy: Think of this as an early race in a championship regatta, with the two best teams already fighting for the lead. They naturally take every advantage of every rule and opportunity (small and large) in their effort to win, because unless they win the whole effort will seem a waste of time and effort. They engage in a little pre-race intimidation. They keep a close eye on each other on the starting line. They mislead each other about their speed and tactical assumptions. They exploit the rules when they can, avoiding dangerous situations and trumping the other guy when they can. There’s bluffing and counter-bluffing as each team looks for the most minute advantage that might quickly open up into a chasm into which the other guy will fall.

All this is done under the rules, of course. If a team oversteps, it can expect to be hailed into court–I mean the jury room. But no racing boat worth its team T-shirt will be irresponsible enough to 1), refuse to force advantages and 2), take advantage of every opportunity it can get.

We’re now in the second race of what may be a very long legal regatta. SNG/Alinghi has already been penalized for ignoring a straightforward rule that it could have observed. Now SNG says that Golden Gate/Oracle has made the same error and should be DSQed as challenger of record because it offered misleading information about the boat it wants to sail in the races. The reason SNG gives may seem nitpicking and irrelevant, but it may produce that much-desired chasm.

When Golden Gate challenged, it satisfied a provision in the rules for the America’s Cup requiring a challenger to provide the boat’s rig, length, and beam. There is no requirement in the rules that the challenger describe the type of yacht it will sail. Yet, because the dimensions provided by Golden Gate more than suggest that the boat will be exceptionally wide, sailors who have studied the challenge believe that the boat will be a multihull. In fact, the former counsel for SNG, Hamish Ross, stated publicly last year that Golden Gate’s boat could only be a multihull, but he is now off sailing back home in New Zealand, and his former colleagues beg to differ.

Golden Gate has not described the boat as a multihull, but it has described it as a “keel yacht.” Why it did that is a mystery because, once again, such a description is not required by the rules. One close observer of the legal war, Cory Friedman, has suggested that someone at Golden Gate or its law firm was instructed to use the 1987 “big boat” challenge of Michael Fay’s Mercury Bay Boating Club to the San Diego Yacht Club as a template, and simply included Fay’s accurate words “keel yacht” in the wording, having no idea what those words mean (and even less that they might stir up trouble). Ostrager cried foul and argued that Golden Gate’s challenge must be rejected because, he claimed, a “keel yacht” cannot be a multihull.

In other words, he said that a description is required by the rules, and that Golden Gate’s is a lie, even though Golden Gate has never said that its boat is a multihull. Shocked as he was that the other side would do such a thing, he gave two reasons for his complaint. First, only a monohull can have a keel, which he defined solely as a heavy fin projecting down from the hull of the boat (more on that later). Second, he said, the defender has a right to know what type of boat is challenging. “SNG needs to determine what type of boat to build,” Ostrager told the judge in January. He did not cite a rule or a tradition that this is required. In fact, he could not have done so because neither exists.

In defense of his statement that a multihull cannot also be a “keel yacht,” Ostrager referred to a letter he had received on January 21 from Jerome Pels, secretary general of the International Sailing Federation, the international governing body of sailboat racing. Ostrager claimed that this letter (which I’m sure ISAF now deeply regrets) supported his absolute statement that no multihull can have a keel. In fact, the letter, which SNG released publicly after the hearing, does not make such a statement and has many qualifications. “Multihulls usually have no ballasted keels,” Pels wrote, indicating that catamarans and trimarans can have keels. Pels also wrote that in the sailing Olympics–the only event he mentioned–multihulls are not classified as keel yachts.

On that basis, and others that he produced from various expert witnesses, sailing manuals, and rule books, Ostrager has asked the judge to disqualify Golden Gate as the challenger of record because the mention of “keel yacht” made the challenge improper and unacceptable. If Justice Cahn will not disqualify Golden Gate, Ostrager insists, he should hold a hearing on the technical questions, with expert witnesses. Otherwise, the judge should hand over jurisdiction in the case to ISAF. The last point took the judge (who is a man of considerable authority and reputation) by surprise. “You’re saying that I should refer these issues to the ISAF?” he asked. “Yes,” replied Ostrager, “A keel yacht is incompatible with a multihull boat.”

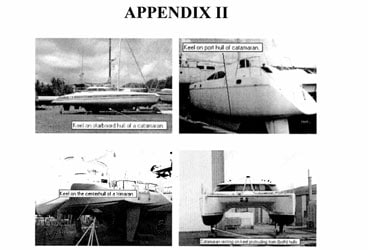

Golden Gate vigorously disputed SNG’s argument. Kearney told the judge that because a description of the type of boat is not required by the rules, the words “keel yacht” are irrelevant. The challenge satisfied all the deed of gift requirements, so is legal. Even then, he insisted, SNG was wrong to claim that keels are incompatible with multihulls. “Catamarans can have keels and catamarans do have keels,” he stated, his voice rising in frustration. “The very notion that they would tell the court that catamarans do not have keels is a delaying tactic.” He later provided photographs of multihulls with all sorts of keels. (The Alinghi and GGYC Web sites are running all this paperwork.)

Kearney (and sailors who attended the hearing) noted that SNG was using only one definition of the word “keel.” Its oldest meaning is a girder, length of wood, or other long structural member located in the center of the bottom of a boat to hold the hull together and make it rigid. This type of keel is sometimes referred to as a “backbone” because it serves the same role as the human backbone.

Sailing language, of course, is very old and sometimes confusing. Another definition of “keel” describes a fin projecting down from the hull to improve a sailboat’s performance. Centerboards have been called “sliding keels.” Some of these keels are made entirely of wood or some other lightweight material and serve to prevent the boat from being pushed sideways. Others contain a weight called ballast, usually comprising lead, that counters the tipping forces of the wind and keeps the boat from capsizing.

SNG’s argument clearly was referring to this last definition of “keel,” the heavy fin-like ballast keel. Multihulls and other wide boats generally do not have ballast keels because their great width resists tipping. But as is commonly known by sailors, every boat hull has a structural backbone-type of keel, and many boats of all types have unballasted fins. And as many old-timers know, there have been multihulls with ballast keels.

Kearney also offered several procedural arguments, one of which was that until recently SNG had accepted Golden Gate’s description of its boat without question. Therefore, he said, SNG could and should not change its mind as it appeared to be doing with its new argument presented by a new lawyer. “We have lived through a blizzard of new arguments,” Kearney told the judge. He also argued that jurisdiction over the Cup lies in the hands of the New York courts. “Nobody can take from this court responsibility to interpret the deed of gift.” New York courts have overseen the America’s Cup for more than 100 years because the deed of gift is a trust document created by citizens of New York State.

Acknowledging Kearny’s procedural points, Justice Cahn agreed to hear more on the technical issues from both sides. Good judges don’t shoot from the hip.

After the hearing, standing on the steps of the New York State Supreme Court building at 60 Centre Street, in Manhattan, Lucien Masmejan, Alinghi’s chief counsel, said it was his duty to proceed with this case. “As the defender and the trustee of the America’s Cup, we have to be sure to accept only valid challenges. It’s our duty as the trustee of the Cup. We are the trustee. We can’t say, ‘We give up.’ We have a vision and we’re not going to give up that vision.”

When Tom Ehman, the spokesman for Golden Gate Yacht Club, was asked how he would answer a question about the description of the boat as a keel yacht, he answered, “Nobody has asked that question.” Golden Gate’s boat, he said, would have a keel. What kind he did not say.

SNG’s argument came under another challenge on the day after the oral arguments in an affidavit filed with the court by one of Golden Gate’s lawyers, Gina M. Petrocelli. She provided evidence that the rules of the one Olympic multihull class, the Tornado catamaran, include three references to the boat’s having a “keel,” presumably of the backbone type. These rules were approved by the same ISAF whose chief officer appeared to lend modest support to SNG on the “keel yacht” question. The affidavit also included 13 photographs taken from the internet of multihulls with fin-like keels.

Now, what will the judge do with all this? Since Justice Cahn has already shown a propensity for concentrating on the clear words of the America’s Cup’s 121-year-old rules, I’d put my money on these two possibilities: First, he’ll make a minimalist comparison between GGYC’s challenge and the deed’s requirements, which means ignoring the “keel yacht” phrase that for some reason the Oracle people left in their challenge. Second, he will repeat Justice Carmine Ciparick’s advice to Michael Fay’s Mercury Bay Boating Club in 1988, which was essentially, “Build your boats, sail your race, and if you don’t like the results, come back to us.”

In other words, the judge may well say what the rest of us are shouting: “Come on, you two. Go sailing!”