In IMOCA 60 racing, singlehanded sailors often rely on their autopilots to drive, and in the Vendée Globe, they can be the singlehander’s best friend or worst enemy.

“The pilot needs to drive the boat reliably through a full range of conditions,” says naval architect Jesse Naimark-Rowse, electronics engineer for Osprey Technical, which outfits Vendée Globe contenders such as Alex Thomson’s Hugo Boss. “On a grand-prix boat, the instruments measure heel, trim, pitch and roll rates, and have very fast GPS and compasses on top of your standard wind and boatspeed [instrumentation]. This information is calculated to allow the autopilot to steer while surfing and respond to whatever else is influencing the [boat’s] behavior.”

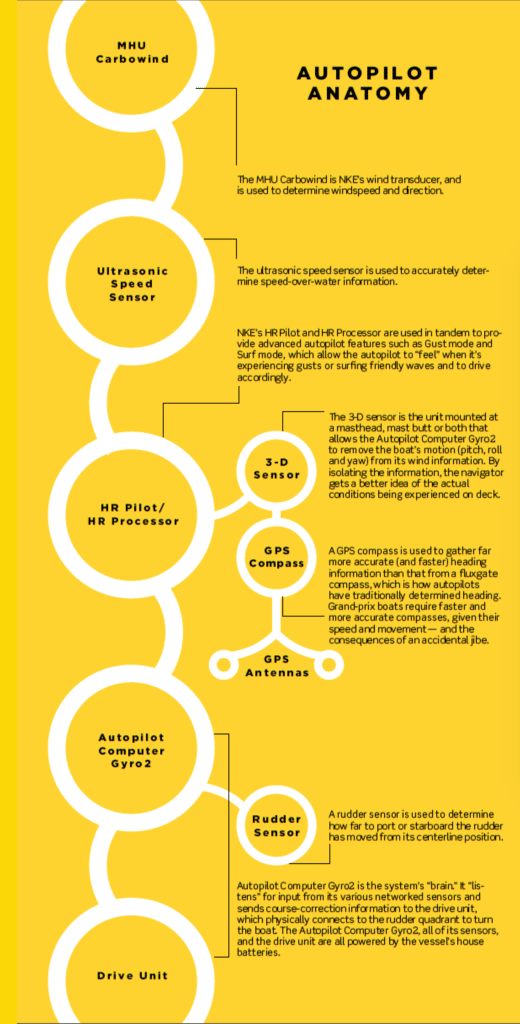

There are many capable autopilots on the market for recreational racers, but B&G and NKE dominate the shorthanded grand-prix market. Solid-state components and advanced algorithms can spell the difference between broaches and podium finishes.

Cutting-edge systems such as NKE’s Processor HR autopilot rely on wind sensors with fast sample rates and solid-state 3-D sensors, in addition to conventional inputs, such as rudder angle. “Our processor samples heel, pitch and roll at 25 hertz,” says Bob Congdon, NKE’s technical consultant. “The processor applies information from [the gyro sensor] and takes the boat’s motion out of the wind equation.” This is critical, he says, because vessel motion can influence an autopilot’s computed windspeed and wind. Grand-prix boats place one solid-state 3-D sensor on the hull and a second sensor at the masthead, allowing skippers to compute real-time mast twist.

However, autopilots can’t see or anticipate windshifts or off-kilter waves and react ahead of time like a human helmsman. “From my experience in waves, particularly upwind slamming, the pilot struggles to match a good helmsman,” says Naimark-Rowse. “In flat water, a good autopilot steering to a wind angle can be so precise that it’s hard for a helmsman to match it.”

Congdon agrees. “Any condition that’s difficult for a human is hard for a computer,” he says, noting that NKE incorporated two new modes — Gust mode and Surf mode — in the Processor HR to help the autopilot compensate. “If the pilot is told to steer a course of 135 degrees true-wind angle and the computer realizes it’s in a puff, it might need to go up to 140 degrees for a moment to keep its speed up and the boat on [its] feet. The computer recognizes the conditions and reacts before a broach.”

Congdon says modern autopilots “use less power because their steering algorithms are so sophisticated, [they] don’t have to overcorrect.” While NKE autopilots provide up to 30 amps to handle the boat, Congdon says that their autopilot-steering algorithms are so accurate that they typically draw only 4 to 5 amps.

Any Vendée veteran will confirm the critical role the autopilot plays in the race. “Most Vendée skippers are hardly hand-steering these days,” says Naimark-Rowse. “The reliability of the pilots has come a long way in the past 10 years, and it only continues to improve.” It’s important to understand, however, that some driving conditions will always be lower-percentage than others. “When a seriously fast boat [takes] off down big waves in strong wind, the risk of an accidental jibe is still a very real possibility,” says Naimark-Rowse, “even with the best autopilot or the best helmsman driving.”