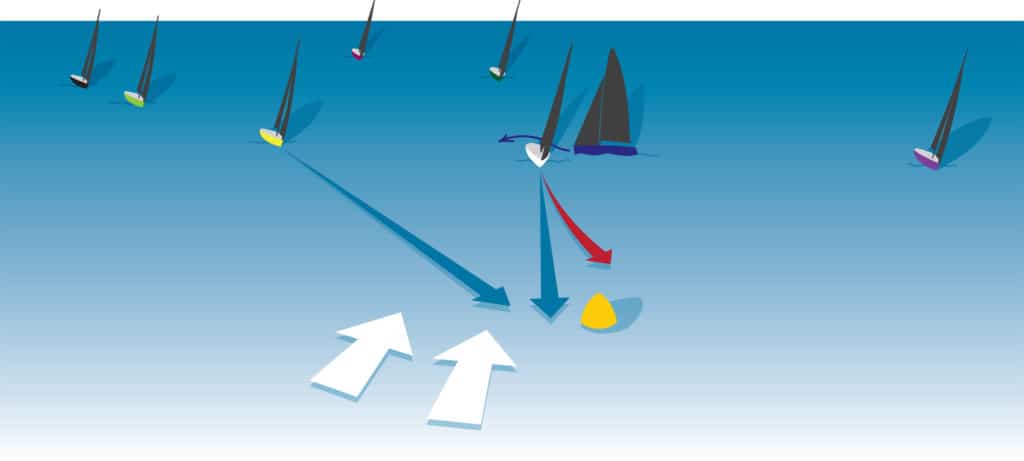

It’s easy to overlook small developments on the racecourse that can quickly lead to big trouble. We’ve all had our moments, but as an observer, I recently witnessed one team experience 60 seconds of pure meltdown, all of it perfectly avoidable — in hindsight, of course. Their troubles were the result of several, little compounding events that left them reeling, and there’s a lot we can learn from their situation. The illustrations on these pages depict a real-life sequence of events, so let’s first explore what happened.

The team we’re watching is the white boat. In the first diagram, they look as if they’re making the mark on starboard tack and, at this point, they look to be leading. A port-tacker (the blue boat) ducks them. That same port boat also chooses to duck the next starboard boat, and then makes a nice tack on their stern. From there, the blue boat’s team knows it will be at least third at the mark, where it can then look for opportunities to pass a boat or two later. I like that way of thinking, especially early in a race or series.

Back to the white boat. They either get a small header or the breeze softens a bit, and they realize they’re not going to make the mark. As they look over their shoulder, they see they don’t have room to tack twice in front of the second-place boat, which now means they’ll have to duck two boats.

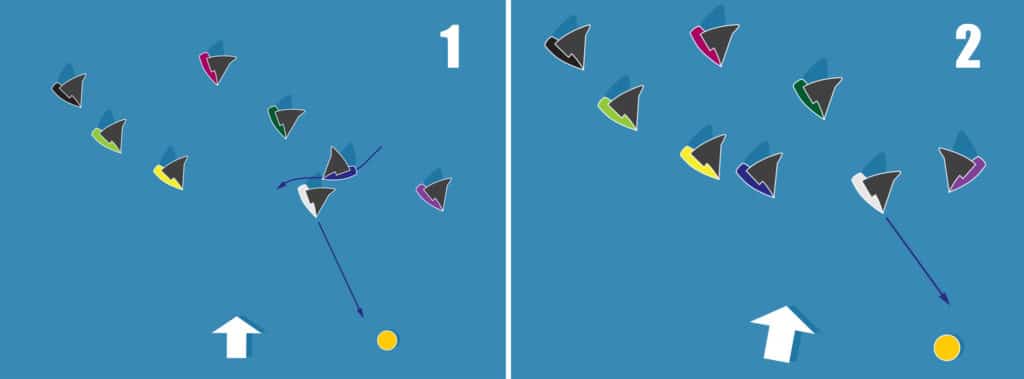

As the fourth boat approaches on port, the white team decides they can’t take any more risk, so they tack in front of the port boat.

The white boat has to duck the two starboard tackers, which turns into a big duck. The boat they tacked ahead of doesn’t have to change course as much, and ends up with an easier maneuver and better boatspeed. Now the white boat is trapped and can’t tack until that fourth-place boat does.

As that boat tacks, white matches, but there’s a starboard boat that shoots through to leeward of them. White now has to stay clear of the leeward boat (which has an inside overlap at the mark) and will round the mark in fifth.

At this point, you could understand that the white team might be getting a bit frustrated. They’ve gone from first to fifth and lost significant distance in just a few seconds and two tacks.

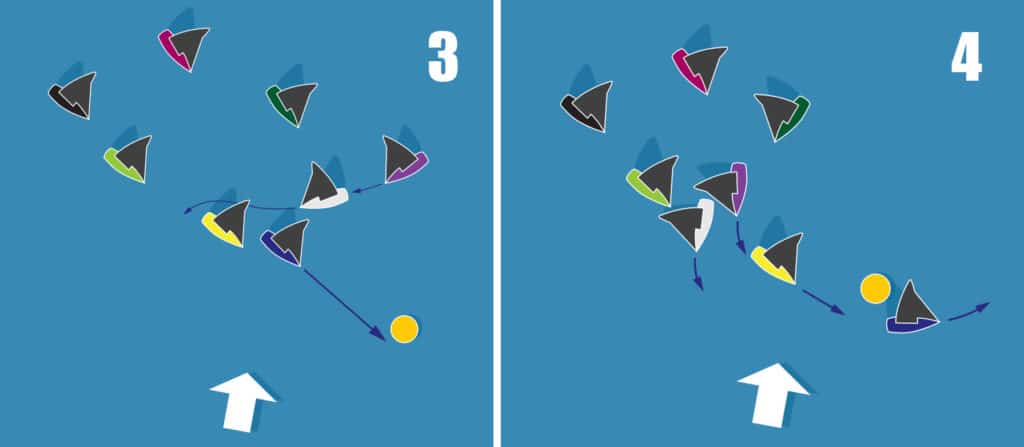

The natural tendency for a team in white’s situation will be to look for an opportunity to make up the distance and points. Fueled by frustration and adrenalin, decisions get rushed and might not be made with full information.

Here, with everyone sailing straight after rounding the mark, white sees an opportunity to split with the fleet and possibly gain back some of the painful loss that just happened. Our guys go for the split but rush the move, and it doesn’t go well.

The helmsman turns too quickly relative to the hoist, the jib doesn’t get trimmed in to fill the fore triangle, and the kite blows through, under the headstay.

The next competitor comes around the mark, does a normal set, and passes our guys almost immediately. In the end, the white boat has to jibe back to correct their mess, losing more boatlengths.

As I said, there is a lot we can learn.

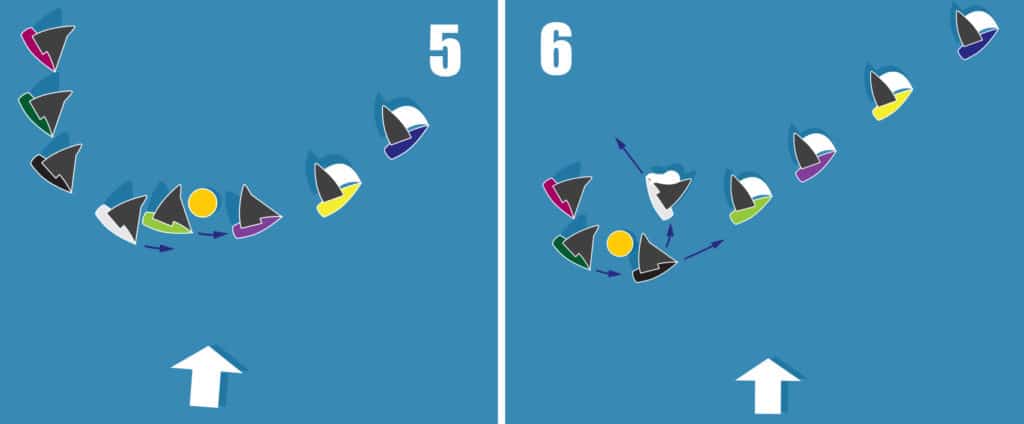

First, it’s critical to always be assessing risk. As we get close to marks, the flow of the fleet gets restricted and lanes shut down. In this scenario, there was a time that white could tack and reset onto the starboard layline before the third boat ducked and made that lane smaller. If they hold on and make the mark, they’re first. If they tack early, they’re second; but if they wait and don’t make the mark, they could drop five places. Is it worth the risk?

In situations like this, I like to hear the words, “Top three at the mark,” or similar, from someone on the team. That reminds me that we’re doing well and don’t need to take a lot of risk.

Maybe the white boat was just really unlucky and, at the last moment, couldn’t make the mark. But more likely, the driver had that suspicious feeling in his or her stomach that they weren’t going to get there. In hindsight, it would have been pretty easy to take away all the risk and tack a few lengths before the first port boat ducked them. There would have been a duck on the starboard boat on the layline, then another tack, and they would have rounded second, living to fight for first later in the race.

Assuming that being under layline wasn’t that obvious, the next time there was an option was just after the blue boat ducked. If the white boat’s team felt at risk at that point, they could have crossed the blue boat and tacked just to windward of them. Both teams would have ducked the starboard boat and then tacked back, leaving the white boat still in second.

If they let more time pass, then the next time to escape was three lengths before the fourth boat was crossing behind them. White would have needed to duck the two starboard tackers, but they would still have had room enough to tack back onto starboard after ducking. The fourth boat would have to duck them, and white would now be third. Not what they wanted, but they’re still in the hunt.

Another move would have been to cross the fourth boat and then tack, leaving white with room when ducking. It’s riskier, however, because the fourth boat might have to ask for room to tack because of the fifth-place boat. Depending on how that plays out, there is risk of fouling for the white boat, or having to tack in a weak position on layline.

Calling for a jibe set isn’t risky in itself. But surely, it was not urgent in this situation. The driver needs to turn slowly, and the trimmers need to have the jib sheet tight so the kite goes around the headstay to set.

The toughest mistake, though, was the last one.

Calling for a jibe set isn’t risky in itself. But surely, it was not urgent in this situation. The driver needs to turn slowly, and the trimmers need to have the jib sheet tight so the kite goes around the headstay to set. To me, this looked like a move born out of frustration and was really the final nail in the white boat’s coffin.

Each of us has responsibilities in situations like this. We need to see the possible risks and help find ways to reduce them. We need to speak up at the right time to allow us to control our own destiny. And then, we need to do our best to keep the boat moving well and handled smoothly, no matter what situation we’re presented with.

There are five boats in this scenario that did nothing more than focus on getting the little, simple things right, and they were all rewarded with point gains. Keep it simple, and respect the value of the little things.