One growth area in our sport is what is popularly called “Beer-Can Racing,” a series of evening races open to boats of all sizes and classes. The emphasis is on fun and simplicity with a minimum of bureaucracy. There are such events near several major cities. Many of them are not sailed under The Racing Rules of Sailing. Some have sailing instructions, some don’t. Most don’t allow protests. The organizers almost always emphasize avoiding contact. One of my favorite lines from such an event’s sailing instructions is: “The regatta will be governed by the simple rule that fun rules.”

Who sails in these races? From my observations, it’s a mix of beginners, experienced racers, and lapsed racers who haven’t raced in a formal regatta for a while. When I’ve sailed in these races, even when the sailing instructions state that the racing rules do not apply, I hear hails, indicating that the hailing boat expects another boat to follow a racing rule. Generally the races conclude without drama. Serious collisions are rare, and everyone enjoys a night of informal competition and camaraderie.

But even though these events have helped sustain our sport in recent years, their failure to use the racing rules is taking informality too far. When the organizers fail to apply the racing rules, it is not the case that there are no rules. There are rules, and those rules are—depending on the body of water on which the races are held—either the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea or the Inland Navigation Rules ( “COLREGS” or “IRPCAS”). These two sets of rules are, for the purposes of a Beer Can Race, essentially identical. They both are intended to prevent collisions between vessels navigating between ports, either via open water or an inland channel. They are decidedly not intended to govern a fleet of sailboats racing in close proximity to one another in an around-the-buoys race.

If you try, as I have, to apply the COLREGS to the many changes of course that every sailboat makes as she starts, rounds marks, and maneuvers in response to the wind and her competitors, you will find many surprising game changes.

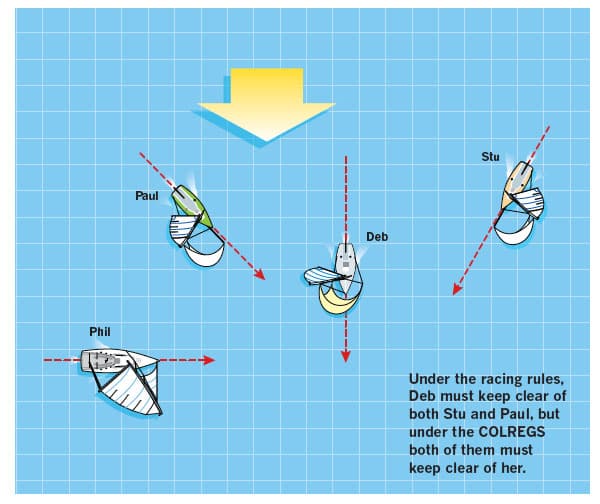

The first diagram shows that the basic right-of-way rules between two boats racing are quite different under the two sets of rules. At first read, you might think the two sets of rules are quite similar because the government rules grant a starboard-tack boat right of way over a port-tack boat and, when boats are on the same tack, they grant a leeward boat right of way over a windward boat (see COLREG 12). But that’s not always the case. There is a government rule that overrides those basic rules. It states that, when one boat is overtaking another, the overtaking boat must keep clear, even if the overtaking boat is on starboard tack, and even if the overtaking boat is the leeward boat (see COLREG 13). In the first diagram, if the racing rules apply, under Rule 10 Stu—on starboard—has right of way over Deb, Paul, and Phil, all of whom are on port. Also, under Rule 11, Phil has right of way over both Paul and Deb, and Paul has right of way over Deb.

Contrast this with the situation under the COLREGS. Under those rules, there are two big differences. Stu, who is sailing a sportboat under spinnaker and overtaking Deb, must keep clear of her even though she is on port tack and he is starboard. Also, Paul, who is also overtaking Deb, must keep clear of her, even though he is the leeward boat and she is windward boat. What’s more, both Paul and Stu must continue to keep clear of Deb until they are “past” her and “clear” of her, even if they change course before they are “past” and “clear.” To make matters a bit more complex in these simple situations, the definition of “overtaking” in the COLREGS depends on the boats using compasses. “A vessel is deemed to be overtaking when coming up with another vessel from a direction more than 22.5 degrees abaft her beam.”

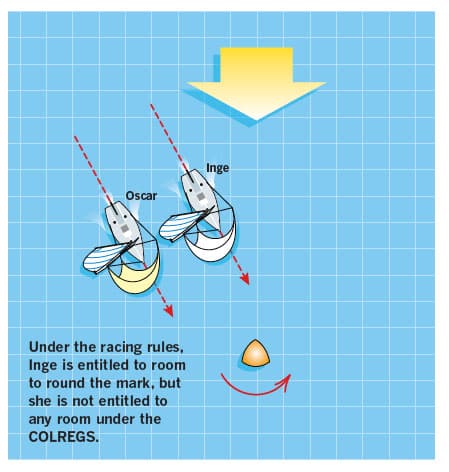

The second diagram shows Inge and Oscar, who have been overlapped for a long time, approaching a leeward mark in open water. They are required to leave to the mark to port. Obviously, under the racing rules Inge would be entitled to mark-room from Oscar. No such rule exists in the COLREGS. Under the government rules, Inge must keep clear of Oscar and she is not entitled to room from him to leave the mark to port.

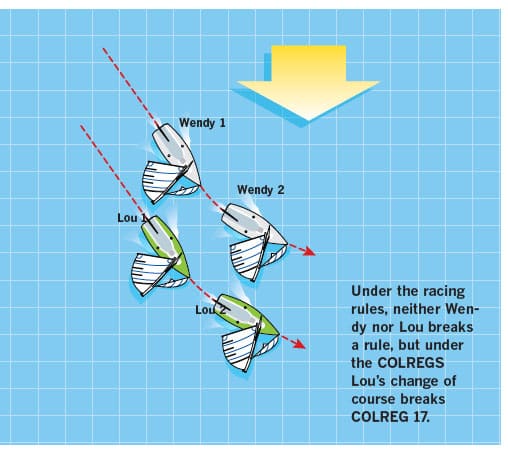

The third diagram shows a very simple luffing situation. Suppose Wendy has overtaken Lou from astern, and Lou luffs her after she is overlapped to windward of him. Provided Lou’s luff is slow enough to give Wendy room to keep clear, Lou breaks no racing rule. Under the COLREGS Lou does break a rule—COLREG 17, which states, “Where one of two vessels is to keep out of the way, the other shall keep her course and speed.” Wendy is required by COLREG 12 to keep out of Lou’s way, and therefore Lou is required to hold his course and maintain his speed. Lou’s luff breaks COLREG 17.

There are major differences between the COLREGS and the racing rules that markedly change the game. The three examples above just scratch the surface. I have tried applying the COLREGS to a fleet of boats tacking up a beat in close proximity to one another. The complexity of the COLREGS in such situations would make your head spin, and it is frequently not at all clear which COLREGS apply and when. Yet the racing rules handle such situations quite simply and easily.

I have not even mentioned the whistle or horn that all the boats in the diagrams would be required to carry on board and sound if they thought that another boat was not going to keep clear. COLREG 34 requires a vessel that is in doubt as to whether another vessel will avoid a collision to give at least five short and rapid blasts on her whistle or horn.

I conclude from this analysis of the two sets of rules that there are major problems with asking racing sailors, who compete under the racing rules in most races, to sail Beer Can races under the COLREGS. It seems to me that the risk of collision is much higher when a race is held under the COLREGS than it is when the racing rules are used. I can easily imagine the chaos at a leeward mark where boats, such as Inge in the diagram, are denied room or where a port-tack boat in Deb’s position demands that Stu, on starboard tack, keep clear of her.

I’ve served as an expert witness in legal cases that involve collisions between racing sailboats. A recent case involved a beer-can race run under the COLREGS. A simple tacking-too-close incident was messy to sort out, and it was clear from the statement of the owner of the damaged boat that he was applying the racing rules—even though the notice for the race stated that the “rules of the road” applied.

Therefore, it is my strong recommendation that beer-can races state in their pre-race publicity (or in their notice of race and sailing instructions, if they issue them) that the races will be governed by The Racing Rules of Sailing.

In order to help them keep the racing simple and fun, beer-can race organizers could provide novice racers with one of two products available from the US SAILING online store. The Handy Guide to the Racing Rules is a short pamphlet containing a simplified version of the Part 2 rules of our sport. The Rules in Brief is a postcard-sized guide containing a summary of the most important rules that apply when boats meet. Each of these products can be bought in bulk at a modest price. Go to www.ussailing.org, click on “store” and then “racing.”