RoseMay06

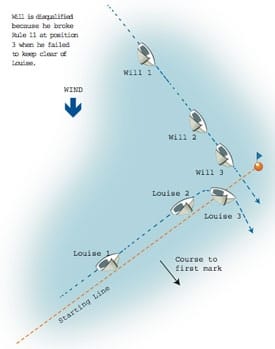

This month I dug into my files and found an assortment of readers’ questions-some basic and some a bit unusual -that cover a variety of topics. Each illustrates that if you want to get to the answer, you must read more than just the principal rule. One J/120 sailor from Detroit, Mich., wrote about a particular point-to-point race that started on a broad reach to the first mark. As shown in the diagram, the wind was from the north, the course to the first mark was 135 degrees, and the starting line was set at a right angle to the first leg.Right of way at the startDownwind starts frequently result in unusual rules situations, and this one was no exception. Both Will and Louise wanted to start at the pin end of the line so they would have a lane of clear air on the first leg. Both approached the line on port tack with Will on a reach and Louise sailing closehauled just to windward of the line. When the starting signal was made the boats were just over two lengths from the pin (position 2 in the diagram) and on a collision course. Will hailed Louise, “Bear off to your proper course!” Louise refused. At position 3, when it became clear to Louise that Will was not going to keep clear of her, Louise bore off and gave Will room to pass between her and the mark. Louise protested Will, claiming that Will, a windward boat, failed to keep clear of her as required by Rule 11. In his defense, Will argued that Louise broke Rule 17.1 by sailing above her proper course after the starting signal. He also claimed that he was entitled to room under Rule 18.2(a) to pass between Louise and the starting mark.There are several issues to be resolved. (1) Was Will entitled to room? If you read just Rule 18.2(a), you would conclude that Will was entitled to room. However, Rule 18.1(a) states that Rule 18 does not apply while boats are approaching a starting mark surrounded by navigable water to start, as Will and Louise were. (2) Was Louise required to bear off to her proper course? There is no proper course before the starting signal (see the Definition Proper Course), so Rule 17.1 did not apply then. Nor did it apply after the starting signal because Louise was not a clear astern boat that became overlapped within two hull lengths to leeward of Will. In fact, the overlap between Louise and Will began before position 1, long before the boats came within two boatlengths of each another. Therefore, Louise was under no obligation to bear off to her proper course after the starting signal. (3) Until Louise blinked and bore off, each boat held her course as they converged, and so the only applicable rules were Rules 11 and 14. By bearing away when it became clear to her that Will was not going to keep clear Louise avoided contact and thereby complied with Rule 14. By failing to keep clear of Louise-either by luffing or by bearing away below Louise-Will broke Rule 11. Decision: disqualify Will.You’re not finished until you finishDr. Robert Paterson, of Gloucester, Mass., asked two questions about how the rules apply at the end of a race. Both involve the meaning of the verb finish, which-in the rules relevant to his questions-appears in italics. A word in italics has a special technical meaning that is different from its everyday meaning. That meaning can be found in the Definitions section at the back of the rulebook.Dr. Paterson notes that Rule 31.1 states “a boat shall not touch . . . a finishing mark after finishing.” He asks, “If a boat has finished, how can she be penalized for touching the mark? The race is over for her, isn’t it?”A boat finishes when “any part of her hull, or crew or equipment in normal position, crosses the finishing line in the direction of the course from the last mark, either for the first time or after taking a penalty under rule 31.2 . . .” However, her race is not quite “finished” in the everyday sense of “finished.” As its first two words indicate, Rule 31.1 applies to a boat while she is racing. Again, because racing is in italics, its meaning is a technical one that differs from the word’s everyday meaning. Check the Definitions one more time and you’ll find that a boat is racing “until she finishes and clears the finishing line and marks.” Therefore, it is quite possible to finish when your bow crosses the line and then, before the entire boat is clear of the line and a nearby finishing mark, to hit that mark. In that case, you may take the one-turn penalty described in Rule 31.2, and then, after sailing completely to the course side of the line, cross the line again in the direction from the last mark of the course. If you do, your first “finish” is cancelled and your finish is recorded as taking place at the moment you cross the line in the direction from the last mark after having taken the penalty in Rule 31.2 (see the Definition finish).Our reader also notes that the phrase “retired after finishing” appears at several places in the rules (see Rules 89.3(a), A4.2, A5, A6.1, A9, and A11). He writes, “I can understand how a boat could retire before she finishes, but if she has finished, she has finished. How can she then retire?”Under the Basic Principle, Sportsmanship and the Rules, if you break a rule you should take a penalty. There is no time limit on taking a penalty. Often a boat involved in an incident doesn’t know whether she broke a rule or not, but after coming ashore and consulting the rulebook her crew realizes they did, indeed, break a rule. According to the Basic Principle they’re still expected to “take a penalty,” but at that time-long after the incident-the Two-Turns Penalty is no longer an option (see Rule 44.1). The only penalty open to her is to retire and, because she is “retiring after finishing,” she will be scored “RAF”, which is normally the points for the finishing place one more than the number of boats entered in the series (see Rules A11 and A4.2).Looking for some redress equityWhile flying his spinnaker on starboard tack, one reader’s spinnaker pole was broken when he was hit by a port-tack boat. That boat acknowledged breaking Rule 10 and took a Two-Turns Penalty. He fashioned a splint for his spinnaker pole and then reset it. At the end of the race, because a boat that was breaking a rule of Part 2 had physically damaged his boat, he requested redress under Rule 62.1(b). He asks what redress he should receive.When it hears such a request, the protest committee must first determine whether the requestee’s score in the race or series was, through no fault of his own, made significantly worse by the damage to his spinnaker pole. He did repair the damage and continue in the race to the best of his ability. Therefore, any worsening of his score was certainly not his fault. However, he will have to argue that the positions or time he lost as a result of the damage constituted a significant loss to him, either in the race or the series. Only if he is successful in this will he entitled to redress. If he is successful, a redress arrangement must be made that is “as fair an arrangement as possible for all boats affected” (see Rule 64.2). The protest committee has a wide variety of options in granting redress. Often redress in such cases is to give the boat her average score in the other races in the series or, if her place in the race was firmly established at the time of the incident, to give her the points for that place and then adjust other boats’ scores accordingly (see Rules 64.2 and A10).E-mail for Dick Rose may be sent to rules@sailingworld.com.