Our rulebook contains only six pages of rules that apply when two or more boats meet on the course. Those are the rules in Part 2, “When Boats Meet.” It’s obvious we need basic right-of-way rules (Rules 10, 11 and 12) and some limitations on the actions of right-of-way boats (Rules 14, 15 and 16.1), but those rules occupy only one of the six pages. Some of the rules on the other five pages puzzle many sailors. Here I’ll discuss why four of those puzzling rules are in the book.

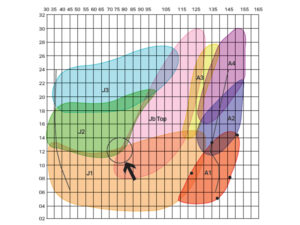

Rule 24.1 is simple: If you’re not racing, don’t interfere with boats that are — it’s basic courtesy. A reader once asked me, however, why the phrase “if reasonably possible” is in the rule. Those words are there to handle fairly the situation shown in the first diagram. Able, Baker and Charlie, sailing closehauled on starboard tack, are nearing the finish line. Able and Baker have identical series scores, and Charlie’s series score is much worse. Able has been slowing Baker by closely covering her in the hopes that Charlie will finish second and Baker third. Able is certainly interfering with Baker by covering her. The rules permit such an action, provided Able is racing. However, at the moment shown in the diagram, Able has finished and cleared the finishing line, and he is well clear of both finishing marks. Therefore Abel has ceased to be racing, Rule 24.1 has begun to apply, and Able is still interfering with Baker. Able must stop interfering with Baker as soon as “reasonably possible.” If he does not, he will break the rule. He could tack or bear away to avoid breaking the rule. His best choice is to tack, as doing so avoids the possibility of his later interfering with Charlie. The phrase “if reasonably possible” is needed in Rule 24.1 so competitors can cover one another at all times while they are racing. Without these words, a boat would have to anticipate interference that might occur immediately after she ceased to be racing and act before that time to avoid breaking the rule.

Another rule that seems mysterious to readers is Rule 18.1(b). This rule is far more complicated than Rule 18.1(a), but many readers, after they spend time dissecting these two rules, cannot see what purpose Rule 18.1(b) serves. They ask, “Why is Rule 18.1(a) not sufficient?”

Rule 18.1(a) states simply that if two boats are on opposite tacks beating to windward, Rule 18 doesn’t apply between them. That’s a well-understood rule that rarely causes problems. The very next rule, Rule 18.1(b), states that Rule 18 does not apply “between boats on opposite tacks when the proper course at the mark for one but not both of them is to tack.”

To understand why Rule 18.1(b) is needed, we need a bit of background. Rule 18 is intended to apply to boats on opposite tacks only when the boats are sailing on a downwind leg at more than 90 degrees to the true wind. Under the definition Overlap, boats on opposite tacks can’t even be overlapped unless both are sailing more than 90 degrees off the wind. However, there are situations that do occur in which boats on opposite tacks, sailing well above 90 degrees to the wind, meet at a mark that does not mark the end of a windward leg. Rule 18.1(b) is needed for such situations.

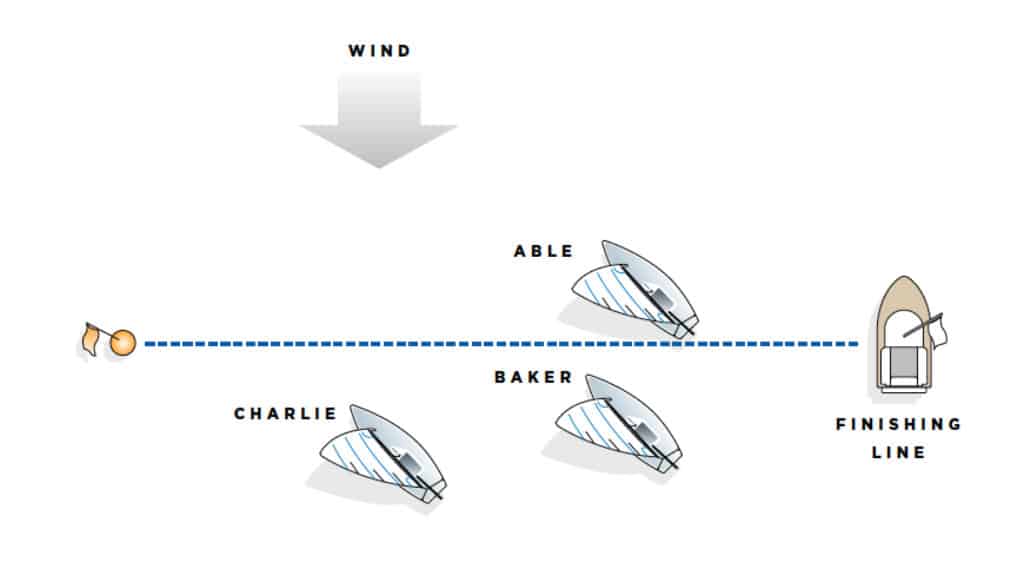

In the second diagram, Rick and Bart are on a reaching leg and about to meet at the mark at the end of that leg. The leg is a close reach, and there is a strong current aligned with the wind, pushing the fleet to leeward. Bart, a lake sailor who had not previously raced in strong current, did not account for the effect of the current by sailing a course higher than the rhumbline course to the mark, and as a result, the current swept him below the mark. He then had to tack and sail closehauled on port tack to get to a position up-current of the mark so he could round it. Rick sailed a higher course than Bart, and so avoided being swept below the mark. At their positions in the diagram, Bart might say that, because of the current, the leg has turned into a beat to windward for him, but Rick is clearly not on a beat. Therefore Rule 18.1(a) does not apply between Bart and Rick.

In order to achieve Rule 18’s intent in this and similar scenarios, Rule 18.1(b) is a necessary part of Rule 18.1. It switches off Rule 18 between Bart and Rick because they are on opposite tacks when the proper course for Bart, but not for Rick, is to tack to round the mark.

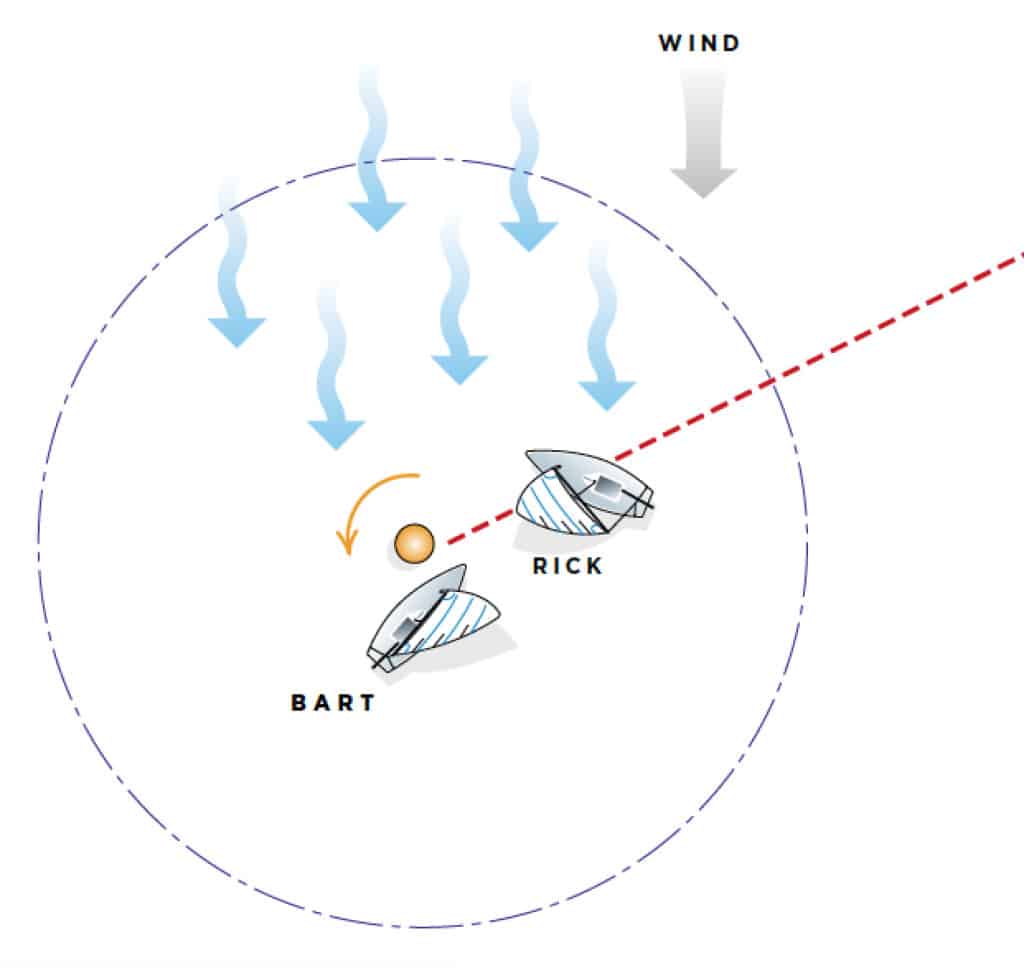

Another puzzling rule for many readers is Rule 18.4. It applies only “when an inside overlapped right-of-way boat must jibe at a mark to sail her proper course.” It’s purely a safety rule. It’s easy to understand how it works by considering the scenario shown in the third diagram. Two boats flying traditional symmetric spinnakers are approaching a jibe mark to be left to port. The wind is strong, and they are broad-reaching on starboard tack. Izzie is overlapped inside Olga. Rule 17 does not limit Izzie’s right to sail above her proper course. The next leg is a beam reach.

Olga has sailed high so she can jibe while running directly downwind. At Position 2, her foredeck crew is on the foredeck and has detached the spinnaker pole from the mast in preparation for jibing. Olga is anticipating that Izzie will comply with Rule 18.4 by bearing off on her proper course and jibing. If Rule 18.4 did not exist, it would be legitimate for Izzie to tactically “attack” Olga by continuing her course on a broad reach and sailing straight past the mark.

Especially in strong winds, this could create a dangerous situation for Olga’s crew, which would be forced to abort its jibe and turn up onto a broad reach on starboard tack. Because Izzie would not have to change course to carry out this attack, this unexpected and aggressive maneuver would not break Rule 16.1. Rule 18.4 was introduced to prohibit such attacks, which were considered dangerous.

Rule 18.4 does not apply at a gate mark because it’s not always clear which gate mark a boat is planning to round. For example, an inside overlapped right-of-way boat in the port gate’s marks zone could be planning to round the starboard gate mark.

Rule 24.2 states, “Except when sailing her proper course, a boat shall not interfere with a boat … sailing on another leg.” I’ve been asked why that part of Rule 24.2 is needed. The answer is that it limits a tactic often used by the series leader in the last race of a series.

Suppose that the series scores for Al and Bill are such that, unless Bill places first or second in the last race, Al will win the series no matter where he finishes. The course for the last race is windward/leeward, twice around. Bill has broken away from the fleet and is leading as he starts up the second windward leg. Al is still on the first leeward leg, buried back in 15th place. If Rule 24.2 were not in the rulebook, Al could simply stop sailing toward the leeward mark and position his boat to slow Bill by closely covering him as he sails upwind. If Al were able to drive Bill back to third place or worse, Al would win the series. Such tactics are considered unsportsmanlike (see Cases 34 and 78 in the World Sailing Case Book). The quoted part of Rule 24.2 clearly prohibits this tactic. Al is permitted to deviate from his proper course to interfere with Bill only if he and Bill are on the same leg of the course. This means that Al must earn the right to use this tactic by managing to get ahead and stay ahead of Bill. Email for Dick Rose may be sent to rules@sailingworld.com.