CloudhopperSt

With so many electronic tools available to the modern offshore navigator, it’s easy to get bogged down in routing programs and GRIB files, only to have all that valuable information go out the window when small, but race-defining cloud features appear on the racecourse. Of course, taking advantage of any cloud features that pop up during the race is what you’re looking to do, and the only way is to prepare, anticipate, and eventually negotiate. It’s impossible to cover all scenarios in this article, but I’ll use a few examples to demonstrate how preparation and proactive “cloud hopping” can win you a race or two.

The tools for the job

To understand what’s happening locally on the racecourse at any given time, it’s important to first have a look at the big picture. For this, I use all forecast tools available before and during a race, including GRIB files and routing programs. I also look at cloud patterns and possible squall scenarios, and one of the more powerful tools for cloud observation is a real-time satellite imagery program, which gives you a recent picture that typically has a better resolution than what you can get off the Internet. Otherwise, watching the satellite pictures available from the Internet and getting a feel for their patterns is the next best option. Before a race, try all the sites you’re thinking of using and make sure that the slower download rate on board will work while you’re underway. Weatherfax, or images on the Internet produced for Weatherfax, is still one of my favorites as well.

A radar unit, which you can use to analyze the formation and travel direction of a cloud feature, as well as its density and possible gust potential, is a valuable resource as well, but on the boats I sail it’s getting harder to convince the “speed merchants” to carry the weight and windage that comes with it. Radar adds a safety element no matter what, especially if fog or squalls are expected, but I’ve won races because I’ve had one onboard, and I’ve won races without one. If the race will take place in a tropical or cold-water venue, I’d favor having it, especially on a larger boat, where the weight is less of an issue.

The most basic and heavily used tool, of course, is a hand-bearing compass, which you’ll use to track the movement of clouds or squall cells. If you forget the hand-bearing compass, you can sight over the boat’s steering compass.

Working the clouds

During the pre-start there should be a discussion with the watch captains and crew about scenarios that may crop up during the race. At this point you can also determine when to alert the navigator of a possible change that could be strategized upon. For example, when racing in mid to lower latitudes around high-pressure zones, and typically when sailing into warmer water, squalls and squall lines can develop. This is a development that requires the navigator’s attention because transitioning through the squalls can reap immediate benefits. I can account for many victories because of this.

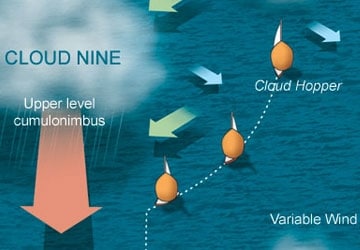

How is this done? Follow along and you’ll see how preparation and a proactive strategy make it possible. Illustration No.1 shows two boats running downwind to a finish, which is about 80 miles away. At roll call, they’re neck and neck while entering a squally area. The watch captain, crew, and navigator onboard Cloud Hopper are keeping an eye out for squall clouds, and they see a particularly large one (Cloud 9) with clouds towering higher than the rest.

After tracking the direction and speed of movement with their hand-bearing compass radar, Cloud Hopper‘s crew observes that Cloud 9 is also growing in size and intensity, and will cause local shifts and pressure. When a cloud is growing, I visualize it inhaling the wind all around it. If a cloud is decaying, it’s exhaling. A large enough squall cloud can act like a small, local low-pressure system, and a boat on the more windward or northern sector in the northern Hemisphere, may observe more wind than one to the south.

Our friends on Cloud Hopper note that Cloud 9 is traveling faster and closer to the mark than the other nearby clouds. They also observe that they are overtaking a smaller cloud ahead, which seems to have stalled (this happens quite often, especially when a particular cloud cell is decaying), so they change their course and head up to avoid the cloud ahead and engage fast-moving Cloud 9. Suddenly, the wind increases and lifts. As it does so, they jibe and enjoy a swift ride to the finish with all hands on deck, jibing as often as necessary to keep the ride going.

Meanwhile, Oblivious, positioned to the south, is having a slow go with Cloud Zero. The crew is to leeward and the drifter is slating against the rig. To the crew of Oblivious, the cloud to their north looks foreboding, and they’re content to wait until it dissipates or moves off.

Seems simple enough, but race after race, this scenario unfolds, and of course, the guys that get it right are geniuses. The guys that get it wrong are darn unlucky.

It is very important to understand that not all clouds move at the same speed or in the same direction, and in Illustration 1, we can see by the large arrow, that clouds that are well formed and rise into upper-level winds will travel much faster than those at lower levels. These upper-level clouds also travel in the direction of the upper wind (more parallel to the isobar lines) and are more likely to bring brief, but strong gusty winds. These winds are briefer ahead of the cloud because they’re moving off rapidly, compared to your boatspeed.

In this scenario, Cloud Hopper‘s navigator likely asked himself several questions: Do I want to go in the direction the fast-moving cloud is traveling? Do I need to engage this cloud to avoid other slow-moving clouds, regardless of where it takes me in the short term? Is the large, fast-moving cloud growing, holding, or dissipating? Such questions need to be discussed sooner, rather than later, because the watch captain may need to rouse the rest of the crew to jibe or peel, and sometimes change to a headsail to escape the dead-air area at the backside of a cloud.

The navigator must also be fairly forceful (convincing) in these situations to persuade watch captains to sometimes jibe away from the favored jibe or a nearby competitor. But he or she must remind everyone that it’s a short-term strategy to either make small gains on shifts, or to stay in good pressure to avoid a parking lot.

I try to clarify with my teammates before a race starts that we’re not going to win every cloud engagement, but, if we engage them proactively, and win the majority of them, we’ll likely beat the guy that’s reacting. Conservative strategy and tactics usually produce conservative results.

One example of cloud strategy played out during the 2006 Newport Bermuda Race. Onboard the Swan 601 Moneypenny, we were facing a light-air upwind scenario, and with most of our competition on the eastern route playing both sides and the middle in light air, there were big gains and losses to be made on shifts. The Weatherfax analysis and forecast were showing a cloud line associated with a weak ridge of high pressure, but the satellite pictures weren’t showing this very well, so visual observation was key. We decided to play the left hard all the way (conservative strategy, conservative results), and were looking for the best time to tack on a permanent left shift. Too early and we’d miss the shift, too late and we’d overstand and get beaten by someone cutting the corner.

We had been playing smaller shifts through local clouds and came in sight of the TP 52 Bambakou. At the time, we knew most of our fleet had worked more to the right but closer to Bermuda. The ondeck watch spotted a dark area of clouds with rain and called me on deck. I could see that on our present course on port we would sail into a dark area where several clouds had stacked up together. We thought Bambakou was just far enough ahead to make it through before that path closed down (and we later learned from them that had we followed, we would have parked). So we decided to tack to starboard toward a clear area in the cloud line, even though starboard tack was less favored.

Once on our new tack, the clear area we were aiming for started closing in as well, and we encountered shifty light winds with rain for a period. We had determined before from Weatherfax and visual, that the shortest way through the line was on starboard, so we had to stick to our conviction. Sure enough, we broke through into clear skies and shortly into better wind with 15-degree left shift. We tacked to port, and except for a 15-minute tack to take advantage of a shift from a local cloud, we laid the finish perfectly from nearly 30 miles away. As it turned out, we needed that entire shift with pressure to beat the guys that had gone right or up the middle.

The obvious lesson here is that no matter how far ahead or behind, one cloud or cloud line can take you from zero to hero or visa versa within minutes, so watch and learn from them. While you pick your way through a cloud minefield it’s helpful to use a Wet Notes pad and draw a bird’s eye view of the strategy you’re trying to achieve; mark the direction the clouds are moving, how you think the wind will shift, and then sketch out the path you’ll take to victory. Clouds, squalls, and cloud lines are not always random occurrences; you can capitalize on them as long as you plan before you engage them.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2007 issue of Sailing World.