Loading a sailboat winch in the correct direction is the first step. Many big-name sailors have fallen victim to this. If there’s any doubt, especially if your boat has counter-rotating winches, put arrows on the top of the winch or on the deck around the base of the winch. It may not look cool, but neither is putting turns on incorrectly.

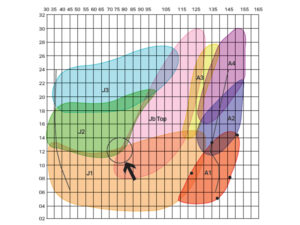

It’s important that the sheet is led to the winch at the correct height. If it’s too low, it can slip down the drum, and if it’s too high, it can lead to regular overrides. The sailing winch manufacturer can provide a drawing with the ideal angle for the lead.

The number of wraps you start with is really a function of rope diameter, drum diameter, and drum surface quality. Smaller-diameter line may require more wraps to prevent the line from slipping on the drum. In general, though, two wraps is a good starting point, and as load increases, you can add more.

Don’t be surprised if, for example, the jib winch requires two wraps on one side and three on the other. The way sailboat winches load, you gain or lose half of a wrap because of where the line starts and finishes on the winch. And with sheets moving at high speed, make sure there’s no slack in the lazy sheet before you start pulling because you can easily end up with an override.

If you do happen to get an override, don’t keep it a secret from the rest of the crew—it’s better that they know, especially if you’re around other boats and need to dip or tack. If you have time, the best method to remove the override is to reverse the lead direction of the sheet (or halyard) and pull the override out, either by hand or by using another winch. Be careful when the override clears itself and gets reloaded. If the override is on the jibsheet and time is short, the best option is to cut the sheet at the clew when tacking. After the tack, reattach the sheet. If you cut the sheet at the winch, it will likely end up being too short. Trust me, I’ve seen it happen.

Winch gearing is all based on required line speed, which means being in the right gear to trim the sail in smoothly at the same rate the apparent-wind angle changes. Driving a sail in and stalling it isn’t fast. On a three-speed winch, first gear is your gross tune for pulling in the majority of the line: one rotation of the handle generally equals one drum turn. In second gear, you’re finishing your trim with the line carrying a lot more load: more winch-handle rotations are required for one drum rotation. Third is your high-load, fine-tune gear.

If your winch has a first-gear button, you’re in luck for jibing asymmetric sails or big genoas. Keeping your momentum going is key. Anticipate when you need to change gears before the load gets too high.

There are a few things you can do to make it easier when using a handle-driven winch with a first-gear button. For example, never put the winch handle directly over the button. This prevents the button from popping up to give you third gear. Also, if you leave the winch handle in the winch, try to leave it pointing to leeward—this helps prevent the handle from swinging down by itself (if you hit a wave, for example) and disengaging first gear.

Speaking of winch handles, a longer handle is a great “extra” gear. Most manufacturers produce both 8-inch and 10-inch handles. If you need more speed, use the short handle. If you need just grunt, say for the backstay, the 10-inch handle gives you 20 percent more power.

There are a few options for the actual handle-grip style and locking mechanism, but in short, the double handle is good for big loads when speed is not as important. The single handle is easy and quick, which is better for smaller boats and lower loads. The speed-grip handle is, in my opinion, the best all-around because it covers both options.

In terms of locking mechanisms, I prefer the newer handles with quick one-handed grip levers that are fast and easy to engage and disengage. If the handle is wobbly or hard to disengage from the winch, it’s probably time to buy a new handle.

A lot of winch technique comes down to experimentation and communication between the trimmer and the grinder. The grinder must be observant of the sail’s needs and anticipate what is required. For example, catching the curl on a spinnaker early requires less grinding and less steering by the helmsman, which equates to speed. If you’re grinding, always watch the telltale signs: the sail itself, the breeze, the helm, and the opposition.

Every boat’s layout is different, so the most efficient stance varies. However, the goal is to get your body over the winch and have a secure position for your legs. A huge amount of your power comes from your core and legs, so you need to be well braced. Where you are depends on many variables, but in light air try to be forward and to leeward. In heavy air, maximize your weight to windward. Either way, stay in a mobile position when you’re not grinding; your body weight is critical to the kinetics of the boat, such as rocking the boat down out of a jibe and roll tacking.

This article first appeared in the March/April 2014 issue of Sailing World. To read more sailing tips, click here.

Winch Wraps