When the scoring system does not permit you to exclude or “throw out” your worst score, a DSQ becomes a significant penalty. For example, if you are averaging third place in an event with 12 entries, a DSQ adds 10 penalty points to your score. Scoring systems used by U.S. high school and college sailing do not permit discard races, which puts a priority on avoiding a scoring disaster. Two recent protests at a high school regional championship provide clear examples.

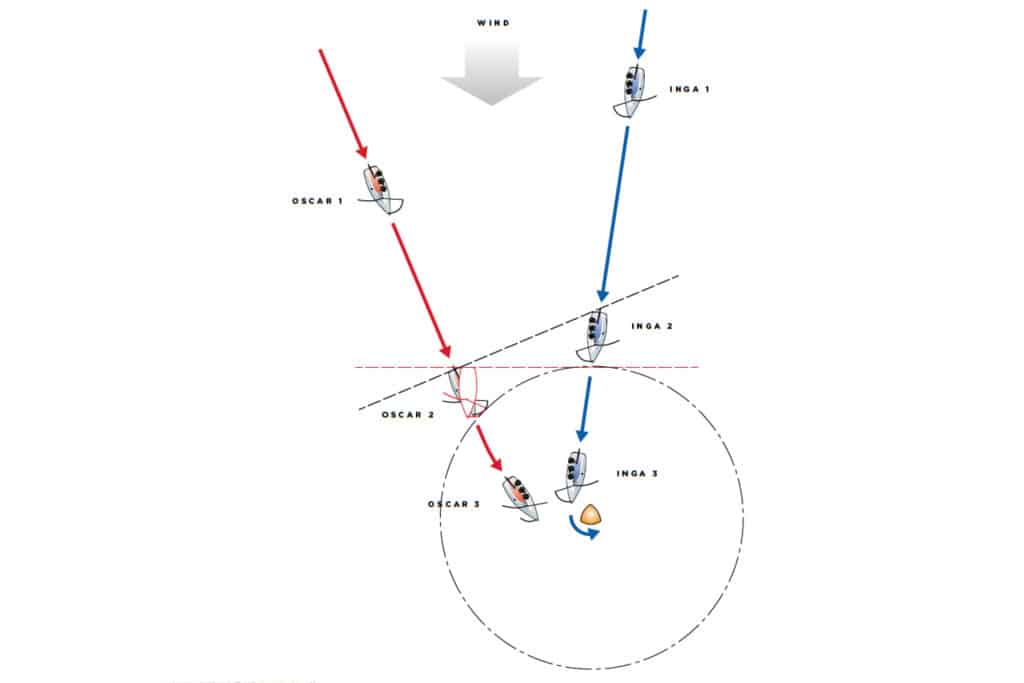

The protestor in the first hearing handled his boat and his protest in a way that insured him against a DSQ. The first diagram shows what happened. Oscar and Inga rounded the windward mark close to each other. Then their courses diverged: Oscar played the right side of the run, and Inga the left. At Position 1, they were on opposite tacks, sailing converging courses toward the leeward mark, to be left to port. When two boats sail converging courses on a run, the likelihood that they will be overlapped is very high. That is the case here. At Position 1, Oscar has an outside overlap on Inga because neither is clear astern of the other.

At Position 2, in an effort to break the overlap, Oscar bore off and hailed, “No overlap! No room!” just as he thought his bow was about to enter the zone. Inga ignored his hail and continued to sail to the mark. Immediately after Position 3, when it was clear to Oscar that his hail had not had the desired effect, Oscar bore away to give Inga mark-room and hailed, “Protest!” Inga rounded inside him and sailed on without taking a penalty.

Later, onshore, Oscar wrote his protest, alleging that he had been clear ahead of Inga when he reached the zone and that Inga failed to give him mark-room as required by Rule 18.2(b)’s second sentence.

The protest committee was careful to take testimony from Oscar, Inga, their crews and the skipper of a nearby boat on the critical issue of whether Oscar and Inga were overlapped at the moment Oscar reached the zone. The committee asked each of these five people to position models to show the relative positions and courses of the boats at that moment. The witnesses did not seem confident as they positioned the models, and they did not agree. Some showed the boats overlapped at the critical moment and some did not. As the diagram shows, it was obvious that just a small change in Oscar’s course could affect whether an overlap existed. However, all five agreed that a few lengths before the boats reached the zone, Oscar had been overlapped outside Inga.

The committee decided there was reasonable doubt that Oscar’s bearaway was sufficiently large and adequately timed so as to eliminate the overlap just as he reached the zone. As Rule 18.2(d) requires in such a situation, the committee presumed the overlap had not been broken. The committee then decided it was Inga who was entitled to mark-room, not Oscar, whose protest was disallowed. However, because Oscar had given Inga mark-room, which the committee decided he was required to do by Rule 18.2(b)’s first sentence, neither boat was disqualified.

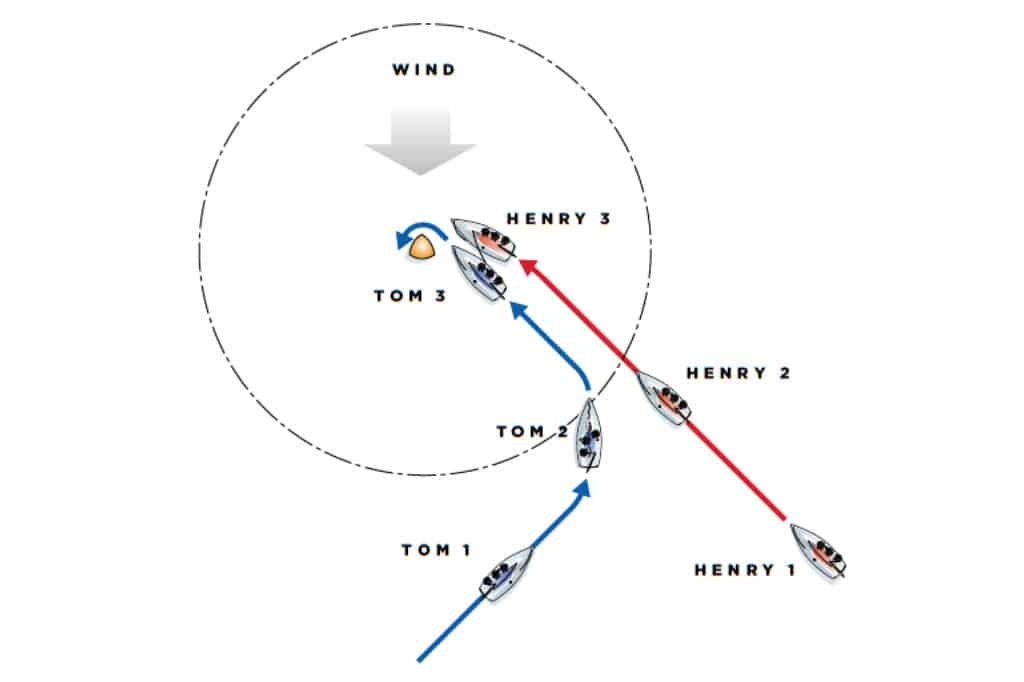

The protestor in the second

hearing handled his boat and his protest in a way that made it quite likely he would be disqualified. The second diagram shows what happened. Henry, on starboard tack, and Tom, on port tack, were approaching each other at the end of the windward leg. Henry was comfortably fetching the windward mark, which was to be left to port. At Position 2, near the perimeter of the zone, Tom tacked to starboard to leeward of Henry, who held his course. Between Position 2 and Position 3, Henry repeatedly and loudly hailed, “No room!” Tom ignored the hails and was able to round the mark without touching it. At Position 3, Henry bore off below closehauled, and his boom touched Tom’s hull. There was no damage. As he rounded the mark, Henry hailed, “Protest!”

The protest committee took testimony from Tom, Henry and their crews, as well as from a member of the protest committee who witnessed the entire incident from a nearby RIB. The committee paid special attention to the critical issue of whether Tom passed head to wind inside or outside the zone. The committee asked each of these five people to position models to show Tom’s position at the moment he passed head to wind. Henry and his crew testified that Tom was clearly inside the zone at that moment, but Tom and his crew and the judge did not agree. Those three testified that Tom passed head to wind outside the zone and had completed his tack when he reached the zone. After weighing the testimony, the committee found as fact that Tom passed head to wind outside the zone.

Henry stated in his protest that Tom had tacked onto starboard inside the zone and then taken mark-room to which he was not entitled. Henry alleged that Tom had tried to take mark-room under Rule 18.2(a), but that Rule 18.3’s first sentence states that Rule 18.2 did not apply. The protest committee reached a very different conclusion. Because it found as fact that Tom had passed head to wind outside the zone, it concluded that Tom was overlapped to leeward of Henry when they reached the zone. Therefore, it decided that at Position 3, Tom had right of way under Rule 11 and was also entitled to mark-room under Rule 18.2(b)’s first sentence. The committee also decided it would have been easy for Henry to avoid contact by simply holding his closehauled course instead of bearing away. The committee then disqualified Henry for breaking three rules: Rule 11 by failing to keep clear of Tom, Rule 14 by failing to avoid contact when it was reasonably possible to do so, and Rule 18.2(b)’s first sentence by failing to give Tom mark-room.

Simple ways to avoid disqualification:

Here are some strategies that will help you keep out of trouble in protest hearings.

• Making contact with another boat almost always risks breaking Rule 14. The risk is highest if you are the keep clear boat and not entitled to room or mark-room. In that case, Rules 14(a) and 14(b) do not soften Rule 14 for you as they do for a right-of-way boat or one entitled to room or mark-room.

• If another boat is claiming a right and you think she does not have it, it is much safer to grant that right to her than to deny it. If you deny her the right and the protest committee finds she did indeed have the right, you will be disqualified (as Henry was). However, if you grant her the right, you can still protest her and, if the committee upholds her claim, you will avoid a DSQ (as Oscar did).

• Remember that the basic right-of-way rules, Rules 10, 11, 12 and 13, almost always apply. Henry forgot this and it cost him. (The only exceptions are when Rule 19.2[c], 22 or 23 applies.)

• A clear, adequately loud, simple hail asserting your view of a situation is usually helpful. Repeating your hails over and over is rarely helpful; it takes your attention away from analyzing the incident and sailing your boat, and the noise you’re making may keep you from hearing an informative response from the boat you’re hailing.

• Keep firmly in mind that different people perceive an incident from different perspectives. You may think that it’s absolutely obvious that you’re in the right, but someone else may surprise you by showing you a different and quite logical way to view the incident and apply the rules to it.

Email for Dick Rose may be sent to rules@sailingworld.com.