Jibing away

I hadn’t enjoyed the previous two Soling Winter Series, and I was not enjoying this one. As the finish of the 2010 series approached, I was depressed and worried that victory would require the winning of every race on the final day and doubtful I could do it. From 1970, when the winter racing of Solings began in Annapolis, until the early 1990s either Sam Merrick or I had won the series, usually by defeating the other on the final day, and for the past 15 years Sam’s longtime tactician, Peter Gleitz, has taken Sam’s place and beaten me in a similar manner with a similar frequency. Two years ago, Gleitz won the final race, and the series finished in a tie broken in his favor. Last year, he won the final race again and edged me out by a hundredth of a point.

This winter, as each Sunday approached, I felt progressively more pressured, tense, and anxious. And then, when, as usually happened, the sailing was cancelled because of snow or excessive cold, I felt relieved rather than disappointed and deprived. When I looked back, I realized I had felt this same fear and trepidation during the previous two Winter Series and had often wished for them to be over and behind me. On several occasions I had even considered giving up winter racing altogether.

I asked several of my sailing friends if this sense of pressure (this wish to get it over with) was typical of series racing or just my private hang-up for this particular series. They told me that they hadn’t been aware of any unusual pressure during their Winter Series racing, but that they regularly became tense in the middle and at the end of regattas or series in which the outcome was in doubt and they were in contention and/or when the outcome determined their access to some advanced status or was one of a set of prestigious annual events. They felt less pressure at the start of an event (when everyone had an equal score and the same potential for victory or defeat, and when their incompetence had yet to be revealed), if the outcome was preordained, if they were not in contention, or if little or no significance was attached to the outcome.

My involvement in Winter Series racing met all of my friends’ criteria for a sense of pressure: I was always in contention (over the 40-plus years of winter racing, I had won more than half of the events and had always been second when I failed to win), the series seemed always to be in its middle or at its end, and its outcome was always recorded as one more or one less victory on my list of all-time Winter Series victories. But this kind of anxiety and pressure—the hazard of losing and the risk of displaying one’s incompetence—is what attracts us to competition. This is the fear that provides the excitement, the satisfaction, and the opportunity to display our bravery. This fear does not distress us nor drive us away from competition.

I found myself thinking about the racing constantly and trying to figure out what was causing my distress, what was different about the Winter Series racing. The previous season had been a good one, the boat had been going fast, and I certainly hadn’t felt this way during the summer.

Finally, as the 2010 series approached its final day, I began to gain some insight. (Perhaps the publication of my new book, The Code of Competition, had forced me to examine my own behavior a bit more closely.) I realized—suddenly—that at the finish of the last two Winter Series I had given up. On the last day I had “choked.” When victory would have required winning every race on that day, I had decided I could not win. I had surrendered in advance. And subsequently (the light dawned!) I realized the anguish and depression I was now feeling were consequent to my fear of doing the same thing again.

I had been miserable after those previous defeats, and I had been belaboring myself with the fear that I was going to give up and lose another Winter Series. I no sooner had this insight than I felt relieved. Once again sailing the Winter Series was going to be fun!

I now saw that the misery I had felt was consequent to a different kind of fear. This fear had made me want to avoid racing, had made me want to get it over with, had made me prefer losing to competing. Instead of being exciting and appealing, this fear had been frightening, depressing, and demoralizing.

Competitors are ambivalent about winning and losing. Along with drives to fight, control, and conquer, we are all endowed with drives to please our opponents, to support them and their intentions, to limit ourselves to a proper place in our hierarchy, and to beat no one who is more deserving. We all wish to be accepted and acceptable. Rather than to deprive our friends of what they most desire—beating us —some of us would rather lose. But the possibility that we will actually give in to that wish, that we will take the easy way out—that we will reveal ourselves as cowards—is unacceptable and frightening. For two years, I had denied the possibility, and for many months, whenever my thoughts turned to racing, I had been punishing myself with anxiety and depression.

When the going gets tough, the competitor’s sense of pressure is not due only to his fear that he will be beaten—that fear is, after all, always present—but also to his fear that he will be unable to hang in there and fight to the last, that instead he will bow out by choosing to lose. He is not conscious of the protracted pain and distress that will develop subsequent to his losing and the exposure of his helplessness and his cowardice. He is only aware of an unbearable pressure to resolve his ambivalence—to either win or to lose—to get it over with.

Losing is the solution of choice not only because it is readily available—the easy way out—but rather because it permits the retention of a semblance of control. Success, victory, and conquest require a continuance of the fearful ambivalence, risk a loss of control, and provide no certainty of outcome. Losing (doing that which ensures a loss) instantly eliminates the ambivalence and establishes control (You didn’t beat me; I beat myself!). And the outcome is certain.

We have all inherited, as part of our need to be acceptable members of a pack, a need to lose. Some of us (the great competitors, the pros) are merely more resistant to this wish than others. Most of us become, periodically at least, preoccupied with the conflict between this need and our need to win, and therefore less attentive to the factors that lead to victory. Many, when semi-consciously aware of this ambivalence, choose, irrationally, to eliminate it by losing.

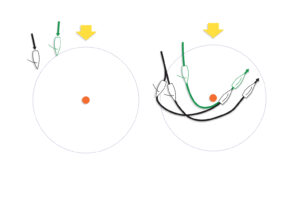

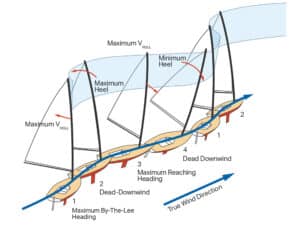

Taking the easy way out by missing the putt, throwing the ball over the middle of the plate, double faulting, jibing away from the fleet, committing one’s self to a loss is common, because it is easy. It maintains our sense of control, demonstrates we are good guys, shows that we are supportive members of our pack, and instantaneously resolves the fearful ambivalence.

Get it over with!

Doing so provides an amazingly persistent (often until the end of the race) sense of calm, satisfaction, and accomplishment. And sometimes the ability to deny, for as long as two years in my case, that it ever happened.

On the final day of the 2010 Winter Series, having finally understood the source of my troubles, I felt confident and aggressive. I decided that winning every race was perfectly possible, and determined to do so. I won the first two and took the series lead with the realization that if I lost the third I would drop back to series second. So I won the third race and the series.

There is no escape from fear. We must face it. “Courage is always the surest wisdom,” says Wilfred Grenfels; the only wisdom, say I. On that final day, armed with insight, I did what I needed to do, and I won.