FTE racing in waves

The day before the first race of the 2009 Melges 32 Gold Cup in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., the kick-off to the class’s winter series, it blew 25 knots with big waves. By the first race, the wind dropped to 5 knots, with leftover 2-foot waves coming at 40 degrees to the right of the wind. This made one tack dead into the waves. Each time a boat slammed into a wave, it would then have to reaccelerate. A slight lift or a little more pressure pushed the bow just above the slamming angle and allowed that team to take off. Anyone caught in a light spot or a header stopped dead, as footing meant heading directly into the teeth of the waves.

Most venues don’t have such extreme differences between the wind and wave direction, but it’s not unusual, even on an small, inland lake, for one tack to feel considerably better, or worse, or simply different than the other. On one tack, the waves might be right on the bow, and you’re banging into them—“chopping wood.” On the other tack, the waves are pushing the boat sideways. Clearly, the wind and waves are not aligned, and if your boat is set up identically for both tacks—jib leads in the same place, backstay and sheet tension the same—you’ll be paying a big price in the speed department.

To be fast on both tacks, the most important sail setup considerations are depth and twist. There are other considerations, but these are the two most important ones and the two you can most easily adjust for each tack. I think about it this way: when the waves are not aligned with the wind, you need to set the sails up with more twist and greater depth on one tack.

Stay out of the woodshed

At the Gold Cup that day, port tack was right into the waves, so we set up the sails with twist and a fair amount of depth. If you only let the sheet out to twist the sail, you’ll loose too much power. That’s why we need deeper sails. Think of this as the “wave mode.” Here’s what you can do, from the back of the boat forward.

With the main, you want the clew to be further to windward and the top of the sail a little more open. Start by moving the traveler to windward. Ease the mainsheet a little to open the top of the leech, ease the backstay slightly to add depth to the top two-thirds of the sail, and ease the outhaul to kick the lower battens to windward a little bit and provide slightly more depth down low. On a boat like a J/24, you’re playing the backstay, traveler, and mainsheet—that whole loop—from tack to tack, so you’re always balancing those three controls. If it’s rough, you’re moving the traveler up, easing the backstay a little, and easing the sheet slightly.

If you were observing from behind the boat and looking at the sail, instead of seeing a relatively straight leech, as you would see in smooth water conditions, you’d now see the bottom corner—the clew of the sail—a little further to windward, the top of the leech a little more to leeward, and the middle of the leech in the same spot as it would be with a straight leech. The rougher it is, the more we need to bring to windward the bottom of the leech while opening up the top. Twist the leech off, and then make the sail deeper by easing the backstay, and you’ll have the same amount of power as the flat water setup except you’ll have a twisted leech profile that will be more forgiving.

Once the main is set, we match the jib shape to that. On the Melges 32, we kicked the jib lead forward an inch or two and eased the jib sheet. Moving the jib lead forward has the same effect on the jib as easing the outhaul has on the main—it adds depth to the bottom of the sail. Easing the jib sheet produced a similar result to moving the main traveler to windward—the top twisted off a little more. The upper jib leech was at about the same spot on the spreaders, maybe a little more open, but there was more overall twist, and the lower leech kicked slightly to windward. That “return” to windward of the bottom part of the jib shoots the wind back into the main a little more. If we can also inhaul a bit, we do that as well.

On the fast tack

After pounding into waves on one tack, the other seemed quiet and fast, so we set the boat up for the 5 knots of wind, but as if the sea state was flat: a straight leech for both the jib and main. Tighten the backstay and pull on a lot of sheet, tightening the leech, and lower the traveler. This is the “flat water mode.”

Remember, you want to keep the middle of the sail in the same position as when sailing straight into the chop, but close the top leech and straighten the bottom leech so that there is less overall twist. Jib leads on this tack should be at their flat-water position, and you’ll sheet the jib a little harder to straighten the leech so that it matches the leech profile of the mainsail.

Occasionally, you might find the waves coming well to the side of the boat, almost like you’re reaching. In this situation, I carry a little more helm than I would in the flat-water mode because, when the wave hits the bow side-on, the additional helm prevents the waves from pushing the bow to leeward. To do that, sheet the main more than normal but leave the jib alone. So, as waves push the bow down, the entire mainsail leech is working to keep the boat up: the mainsail is fighting for you, and that will keep the boat sailing straight.

How much twist do you need?

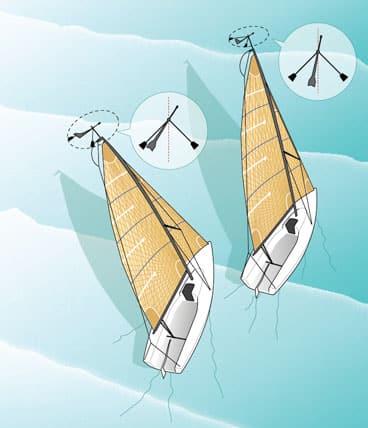

For most people, the wave mode is the most challenging. As someone who spent a lot of time near the masthead over the past few years [Horton was regularly perched atop Luna Rossa’s mast in the 32nd America’s Cup challenger trials—Ed.], you think about how much the top of the mast is moving. The masthead fly is an indicator of that. Every time the bow goes down a wave, the top of the mast goes forward and the wind comes more from the bow (see diagram on p. 64).You’ll see that movement reflected in the direction of the masthead fly. Then, when the bow comes up and the mast moves aft, the masthead fly will point more to the side. When it’s wavy—and this works on every boat—watch the masthead fly as the boat is sailing upwind. As the boat pitches, the masthead fly will move. If it’s moving a lot, you need lots of depth and twist. If it’s not moving much, you really don’t need much of either.

As I look at the masthead fly moving forward and aft, I try to “freeze-frame” the two extreme positions. I think, “OK, if the wind indicator is all the way back, as in a lift, what would my mainsail look like?” The answer is that it’s like a very close reach, so you’d have the mainsheet eased and a little more depth in the sail.

When the masthead fly is forward, such as when the bow is coming down a wave and the boat appears headed, the sail would ideally be set up with a tighter leech and not much depth. Most boats can’t shift gears that quickly, so think of the sail in thirds. The top portion is the lifted part, when the mast is coming back, the middle is for power, and the bottom is the headed part, when the mast is moving forward. With that setup, part of the sail is always trimmed for the range of wind you’re seeing. The top of the sail is trimmed for the “reach” situation, the bottom for the “header situation,” and the mid-leech for anything in between.

If you hit a wave, stop, and don’t accelerate very quickly, you’re probably not twisting enough. Shift into the wave mode. Another reason to move to the wave mode is when you need to be able to steer to avoid the big waves, but every time you try to put the bow down to accelerate, the boat heels way over. The flat-water setup won’t allow that amount of course variation.

When do you move back to the flat-water setup? As the boat pitches and the apparent wind changes, watch where the sail starts luffing, or breaking up. When the mast moves forward and your sail breaks up just at the top, then it’s probably too full and too twisted. And if you’re fighting to keep the boat on track because of waves coming from the side, it’s time for the flat water mode.

As a rule of thumb, I try to set up the sails with the least amount of twist that I can get away with. I’m not going to go out with a flat-water setting if it’s blowing 20 knots with waves on the bow. Inevitably, what will happen when you twist too much is that you won’t point as high. If you’re looking at photos, a good indicator that you’re twisting too much is that the middle leech has moved to leeward. This is tough to see from onboard.

When you’re two-boat testing before a race, and you’re sailing on the tack that takes you more into the waves, be sure to give it some time. Waves really affect boat speed. You can’t just sail for 30 seconds and say, “We’re faster than that guy” or “We’re slower than that guy.” One bad wave will stop you, and one bad wave will stop the other boat. You have to go through that whole cycle of stopping, accelerating up to speed, and pointing a few times to figure out who’s actually set up correctly.

Keep in mind the two modes and how to get there. Always add depth when you’re twisting the sails. And remember, both sails work in harmony. If you adjust one, you should definitely be adjusting the other.