At age 42, the 63″, 200-pounds Trevor Baylis may not be your stereotypical high-performance dinghy crew, but his record shows hes one of the best. He had a banner year in 2001, dominating the International 14 Worlds with veteran skipper Zach Berkowitz, and then winning the 18-Foot Skiff Worlds with Howie Hamlin and Mike Martin. Sailing World recently tracked him down at his home in Santa Cruz, Calif., to extract the knowledge of decades on the wire.

**What attributes should a high-performance dinghy crew have? **

All the crewing stuff breaks down into three things: boatspeed, boathandling, and tactics. The attributes are different for each. To develop speed, you need to be able to feel the boat. Theres a technical side to it–of having an image in your brain about what the rig should look like–but in high-performance boats, a big part is how the boat feels, and a lot of that comes from driving. At any 505 regatta, the boats that are fastest downwind have crews who are good drivers. Youve got to be able to feel whether the boat is slow, sticky, or not accelerating well in the puffs. In general, I think crews dont focus enough on making sure they get out and learn how to just sail the boat fast.

**So, to become a better crew one must become a better driver? **

You need to build a shared vocabulary, and thats easier if both people know how to drive; thats why teams that have been together longer will be faster than teams with lots of raw talent, but lacking in hours. One thing Zach and I did last year was go sailing–what we called “harbor tours.” It goes against the current dogma of college dinghy sailing, but wed just go out and tweak, tune, and adjust. Before long, we got to know what we were each looking for. It would be just long, straight-line stuff–only eight tacks or eight jibes in a two-hour sail.

**What about the other two attributes: tactics and boathandling? **

I think most crews emphasize boathandling too much. In a skiff, boathandlings not the crews most important job. Most beats require only two to four tacks. Its nice to be able to out-tack someone, but its not that critical. You need the boatspeed between the tacks and you need to be headed in the right direction. High-performance dinghies tack poorly and tacks are expensive, so you first have to be going fast in the right direction. A boathandling-oriented crew may tend to be focused in the boat rather than out of the boat, and to do well, you need to be focused outside the boat.

**How does one keep their head out of the boat? **

One way is to be constantly calling puffs, trying to predict them aloud. Saying “Header in six,” and then count down and see if the puff comes at the rate you think it will. One little trick to give the skipper more information is to say “Puff in 4,” and then count down, “4-3-2-2-2-2-1.” Hell know that the puffs moving slower than you predicted, and he knows youre trying. I dont do that, but Ive trained myself to look around every once in a while, to flick back and forth in focus from boatspeed to tactics. Having to do all that talking drives me nuts, although I love when someone else calls the puffs for the driver.

**On high-performance boats, the crews tactical role is paramount; any fundamental advice? **

Everyone has their style, so its hard to make generalizations beyond the obvious; sail fast in the right direction. Charlie McKee, for example, has an interesting way of looking at tactics. First, he tries to make some big decisions before the race by going up the first beat and determining whether its better to be in the middle or on the edges. Then he shifts his tactical game to either edge-game mode or middle-mode. Hes really good at figuring out two or three steps ahead by predicting how the fleet will move.

I tend to look for lanes and then try to go blazing fast, since Im not that good at trying to predict what other boats are going to do, and then working out what I should do based on that information. Kevin Hall often asked the following question of the top teams in our 49er de-briefs: “If you had to sail every beat exactly the same, what do you think the ideal track would be?” If you can answer that question successfully before the first beat by looking at the wind, land, current, etc., then youre a long way ahead of your competitors.

**What should be the crews role in preparation before a race? **

Whatever it takes to make sure breakdowns dont happen and everything works. Everybodys got their pre-race ritual, and its important to make sure each person is able to do what they feel they need to do to be prepared to race. At least 90 percent of the time Im the first person at the dinghy park–even if I have nothing to do but drink water and hang out. Thats what makes me feel prepared for the day.

One of the things that Zach and I had a hard time figuring out was when the race started–when is it mentally race-mode time? For Zach it was when he got into the starting area, which would amaze me. Hed be sailing down to the line and every maneuver was terribly sloppy, but as soon as we sheeted in at the start, hed be totally focused. It drove me crazy because my race starts when Im putting on my wetsuit onshore. I like to launch the boat crisply and cleanly, and to have that first jibe out of the harbor be powerful.

We eventually came to an agreement that the racing would start as soon as we put on our wetsuits, wed race to the starting line, sailing hard, and then wed take a break and laze around until the 10-minute gun. That was our compromise. It gave us time to look at the beat and come up with our strategy. That way, Zach had an idea what I was trying to do tactically.

**Once in sequence, what should the crew be doing? **

The crew should be focusing on boatspeed and tactics; as well as making sure you dont flip. I think its easy to not pay enough attention to being fast right off the line. Make sure you have your marks–where youll sheet the jib to, the leads, the rig settings– figured out so that youll be 100 percent at the gun. Then look up the course and figure out what the first part of the beat will be and start looking at the line and figure out how to implement that plan, i.e., at what end you want to start and where the smart guys are lining up.

**Up the beat, how do you stay focused on keeping the boatspeed, tactics, and boathandling in balance? **

I put boathandling lowest on the list. Its only before a maneuver that I have to snap out of my looking-all-over reverie and focus on the maneuver. On the 14, for example, we ended up leaving the jib cleated until it backed in the tacks. Right before a tack, Id stare at the little cleat and totally focus on it, because if it werent uncleated, wed flip immediately. You have to go from looking-around-mode to in-the-boat focus mode and then come out of the tack and go back into a boatspeed mode and then start looking around again.

**Whats your view on dialogue with the skipper? **

The sports psychologists, coaches, and my skippers tell me Im bad at it. Two years ago, Rod Davis wrote an article on himself and coaching, and he said that for him silence means youre doing a good job. Praise was to be only for extraordinary stuff. Thats how I do it as well. But I know the skipper needs to have confidence to perform at their best so Im trying to learn to talk and praise more.

**How much feedback do you give? **

I keep it short and sweet: “Were going fast . . . the boat feels bound up . . . lets press hard here.” Its not touchy-feely stuff. Its all about how the boat feels. Again, you try not to say too much–silence means everything is right with the world. I have a hard time verbally “painting a picture” of the fleet and the racecourse for the skipper. For me everything is always in flux, especially in short-course racing, and if you try to describe everything thats going on, chances are that a lot of it will be wrong, as well as distracting. I prefer to work with the driver on boatspeed, and do the observing and tactical calls on my own. On the 18 it was set up so Mike did the tactical stuff, while I concentrated on boatspeed with Howie, and that worked well.

**Can you hit on the most important ingredients of boathandling? **

In the skiffs, there are only two big boathandling issues: one is realizing that the rate of speed with which you cross the boat determines the course the boat sails in the maneuver, the other issue is that you must be consistent. In heavy-air jibes for example, you need to move into the boat slower than you would for light-air jibes, this allows the driver to draw out the turn. Its also important to look at the piece of water youre turning in and decide how fast the driver is going to turn. Thats where being consistent comes in as well, by doing things the same way in all conditions, the driver can confidently turn the boat–knowing exactly what youre going to do.

I like to have only one way of doing things, regardless of the conditions. For example, the driver should always follow the crew in and should always go straight out on the wire–theyve got enough to think about without trying to balance the boat out of the tack or jibe. Balancing is the crews job.

For example, right before a heavy-air jibe I like to remind the skipper, “Ill be on the wire on the other side.” Im trying to tell them “Im not going to get stopped in the middle, so you can keep turning.” Im reassuring the skipper that Im focused, and hopefully that will give him the confidence to do his normal turn. Thats where youre most likely to crash–doing a “custom” jibe, thats different than normal, which usually includes an S-turn and going straight down the back of a wave. You want to come out high so youre not square to the waves. The skipper has to have confidence that youll do the same thing you did in practice, and then you just have to do the job.

**Any advice for new or younger crews getting into high-performance boats? **

Dont be afraid to ask questions. When you first start sailing skiffs you constantly feel as though youre scrambling–youre just trying to keep up with all the stuff thats going on. But theres technique to all of it. Talk to the top teams and theyll tell you that theyre trying to do specific things in a specific order all the time. It may be hard, but start down that path and learn how the good guys do things, and then fine tune and experiment.

**Any final wisdom? **

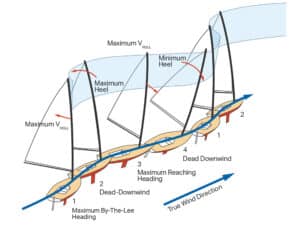

Understand what the tuning does. Its not just a question of boatspeed–with the right tuning, you can make the boat a lot easier to sail. Its important to realize that you have to get the boat so that it feels right and feels good, which goes back to doing harbor tours. If you go sailing all day and end up only doing one or two jibes, thats fine. If you dont do any, thats OK, too. Just get comfortable with the speeds youre sailing at and how the tuning affects the way the boat feels. And if you do figure out the tuning, youll be faster, and if youre faster, good things tend to happen on the racecourse. Theres nothing like boatspeed to make you look like a tactical genius.