Spinnaker staysails have three specific tasks: cleaning up the wind going around the front of the mainsail, moving the center of effort forward to help balance the helm and adding more sail area. Genoa staysails are also used when jib reaching, but that’s mostly an offshore setup, and we’re going to focus sailing around the buoys. A spinnaker staysail has a subtle effect. It’s never going to make the boat just light up and really go, but if you average your speed with a staysail over the length of a leg, you’ll discover you’re definitely sailing faster, and the boat will be more controllable. On the TP52, we think it’s important enough to have the staysail on deck, plugged in and ready to go at the start of any race in which we might use it. On some boats, such as the Melges 32, the jib functions as a staysail, with much the same results.

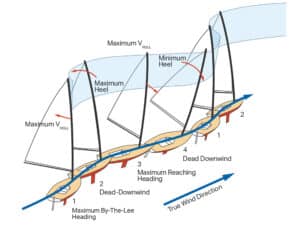

For most high-performance boats, the staysail’s sweet spot is usually somewhere in the 9- to 15-knot range and 140 to 155 degrees off the wind. On smaller high-performance boats, they work best when you’re in the middle of the reaching range — not too tight and not too broad. With a symmetric spinnaker and sailing deep, say 160 or so, such as you might on a Santa Cruz 70, tack the staysail on the windward side of the boat, three-quarters of the way to the bow, which is like pulling the pole back. If you sail with the pole back 45 degrees, the staysail needs to be tacked to windward as well. It follows the pole. As a rule of thumb, however, anytime the pole is on the bow, then the staysail of some variety should be up.

At the top end of the staysail wind range, heavier boats start sailing deeper angles, and most high-performance boats just leave the jib up as a staysail instead of switching. Doing so saves the commotion of getting the jib down and the staysail up at the windward mark, then having to reverse the process at the leeward mark. It’s possible to do it efficiently, but you have to balance the commotion with just using the jib. The jib might not be as great a sail, but you already have it up, and in switching sails, you might lose more than you gain. If it’s right at the crossover for spinnaker staysail use, one trick is to set the staysail on the final leg, so it only has to be deployed and not taken down.

At the lower end of the staysail wind range, there’s a risk the staysail will take pressure off the spinnaker. As the wind drops, there will usually be pressure on the staysail sheet, but the spinnaker sheet pressure will get lighter. To compensate, the spinnaker trimmer will end up oversheeting. The spinnaker becomes unstable, and things quickly go bad. So, the toughest part is at that transition point, which varies from boat to boat. You might discover that the moment you put the staysail away, spinnaker sheet pressure increases, the trimmer can ease the sheet out again and you’ll be able to sail a bit lower.

The type of spinnaker you’re using and the conditions figure into when to use a staysail, especially in the lower-wind transition range. If you’re sailing with a light-wind spinnaker at the top of its range, you can deploy the staysail at a lower windspeed than with a heavier spinnaker at the bottom of its range because you can maintain pressure with the lighter-air spinnaker, but that will be more difficult with a bigger chute, with its heavier material. If you’re in a building breeze with a lighter chute and you’re thinking, I wish I had the big spinnaker up right now, that’s a really good time to use a staysail. The key is to use the staysail to add pressure to the boat but not take too much away from the spinnaker.

If it’s choppy and the boat becomes unstable, the staysail will not help because it once again takes wind away from the spinnaker. It’s also tough to use a staysail in puffy or shifty conditions, or if you’re having to mode and reach around. If you get a big header, it’s time to furl the staysail. Or, if you come into some dirty air, such as at a leeward mark, or the wind gets light, your spinnaker might start getting a little soft, so furl the staysail. The same is true if you have to begin sailing a deep to get away from the bad air. If in doubt about whether the staysail is helping, try furling it. If the other sails immediately start showing more pressure, then you’ve made the right call.

Trimming

If the staysail is trimmed correctly, it will clean up the flow on the leeward front side of the main. The staysail does this like a biplane wing, essentially bringing the breeze around the leeward side of the main and making a slot for the wind. When you look at the sail from the back, the trim of the staysail should match the trim of the main. While the goal is to match the twist of the main and spinnaker, it’s tough to do that because they’re completely different types of sails. The staysail is kind of halfway between, creating progression of twist from the spinnaker to the staysail to the main.

Rule No. 1 is to never, ever overtrim a staysail. You always want the luff a bit soft, so the windward telltales are always lifting. The top of the sail has to be really twisted to match the spinnaker, and the bottom of it must be flatter to match the main, so it’s very common that the top of the sail will appear undersheeted and the bottom oversheeted. It’s tough to get it just right because the sail has a really short chord length, and it’s a really high-aspect sail. If you get a big header that causes the spinnaker to start to luff, quickly burp the staysail sheet. That will momentarily take the staysail out of the equation and allow the flow to reattach to the spinnaker. Once the chute is full, retrim the staysail.

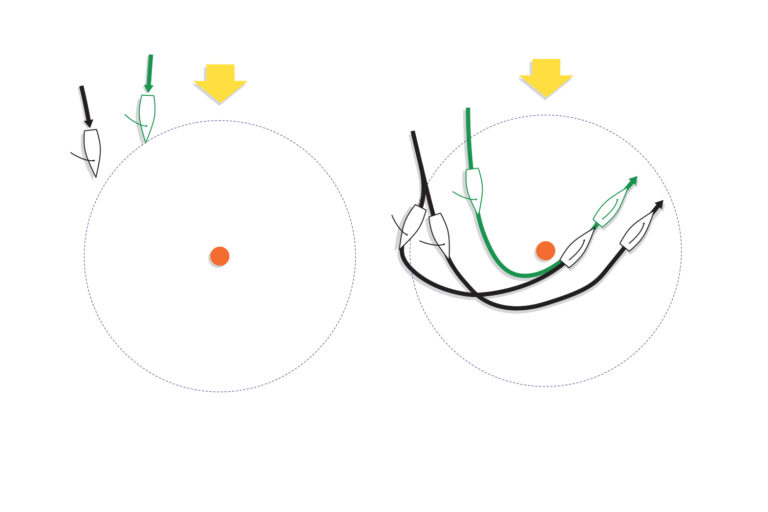

The staysail tack position and the size of the staysail are critical. Usually they’re tacked about 45 percent of the way aft from the spinnaker tack to the mast. Tack the staysail too far forward, and it will take away from the spinnaker. If the staysail is too big, you’ll end up taking pressure off the spinnaker as well.

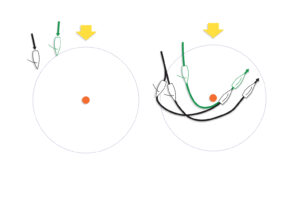

Jibing with a Staysail

Most boats furl the staysail just before the jibe and unfurl it after the boat is to the new downwind angle. One common mistake is to open the staysail too early after the jibe. Because the staysail is set up to be sheeted at a lower sailing angle, unfurling it early only heels the boat and obstructs flow through the slot. For instance, if you typically come out of the jibe 10 degrees higher than your actual jibing angle, the staysail is going to be too full in the bottom for the correct sheet position. So, keep the staysail rolled up until the boat gets down to its normal downwind angle.

Using Jibs as Staysails

A nonfurling jib can be used to act as a staysail, although not as efficiently. The problem is that they don’t have enough shape in them to really do the job, plus they aren’t sheeted in the right place for a reaching staysail. But they can still help. Just be careful during spinnaker sets or when coming out of jibes. If the jib is up and sheeted, you’ll have to sail pretty high to get air between the spinnaker and the jib, making it very likely you’ll wipe out. To prevent that, ease the sheet until the sail luffs, or drop the jib halyard a few feet just as the spinnaker is going up. This allows the top of the jib to twist open. Of course, the sail will also come down a bit, allowing a lot more air between the spinnaker and the jib. Basically, you’re pretending only the bottom half of the jib is there, which still helps balance the boat, allowing you to turn down more efficiently and, once again, allowing more air to get to the spinnaker. You’re basically making the jib disappear for those few key seconds.

Think of staysails this way: There is only a certain amount of pressure you can get from any given wind velocity. A staysail will give you a little bit more, but it takes a percentage away from the spinnaker. If you’re sailing in moderate air without a staysail, you might be getting 80 percent of your pressure from the spinnaker and 20 percent from the mainsail. Add a staysail, and you take 10 percent away from the spinnaker, just a little from the main, but add an extra 5 percent to the whole equation. It’s a small net gain, but as long as it’s used at the correct time, it’s a gain.