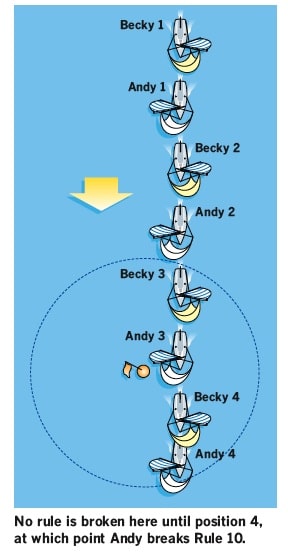

Tony Mooney, of Sydney, Australia, sent me the diagram at right and asked how the rules applied at each position in it. Andy and Becky are running directly downwind on a leg from the windward mark to the leeward mark. The buoy shown marks the outer edge of an anchoring area, and the sailing instructions require boats to leave it to starboard. Therefore, the buoy is a mark according to the definition Mark.

Throughout the incident Andy is on port tack and Becky on starboard. Normally the defined terms clear ahead, clear astern, and overlap do not apply to boats on opposite tacks. However, since 2009, these terms do apply to boats on opposite tacks that “are sailing more than ninety degrees from the true wind” (see the definition Clear Astern and Clear Ahead; Overlap). Therefore, at all times Andy is clear ahead, Becky is clear astern, and the boats are not overlapped. So, you might well ask, “Which boat has right of way? Becky as the starboard-tack boat or Andy as the boat clear ahead?” The answer requires you to pay attention to the introductory “when” phrases in Rules 10 and 12. Rule 10 does apply because the boats are on opposite tacks. Rule 12 does not apply because, even though Andy is clear ahead and the boats are not overlapped, they are not on the same tack. Therefore, Becky has right of way, and she retains it throughout the incident.

Just afer Position 2, when Andy’s hull reaches the zone, Rule 18 begins to apply. Because Andy is clear ahead at that moment, Becky is required by Rule 18.2(b) to give him mark-room. According to the definition Mark-Room, Becky must give Andy space to sail a direct course to a position at which the mark is alongside the starboard side of his bow (Position 3). Then she must give him room to sail his proper course while “at” the mark. In this case, his proper course is simply to sail straight on towards the leeward mark. Andy is entitled to sail to the mark and then straight past it even if Becky must change course to avoid him while he is doing so. If Andy were to break Rule 10 while sailing to and past the mark in that manner, he would be exonerated under Rule 18.5.

When Andy is past the mark and on his proper course to the leeward mark¸ he no longer needs mark-room and so Rule 18.2(b) no longer places any obligation on Becky. However, Andy remains obligated under Rule 10 to keep clear of Becky. Andy should immediately take action to avoid breaking Rule 10. He could jibe, which would switch off Rule 10 and switch on Rule 12, giving him right of way. Or he could luff or bear away so that Becky could continue on her course with no need to avoid him.

In the situation described to me, Andy does not do either of these things. At Position 4, Becky’s spinnaker brushes Andy’s backstay. Andy breaks Rule 10 by failing to keep clear and if protested he would be disqualified. Both boats break Rule 14 by failing to avoid contact when it was reasonably possible to do so. As the right-of-way boat, Becky cannot be penalized for breaking Rule 14 unless the contact causes damage or injury (see Rule 14(b)).

Collisions without fouls

I’d bet most readers believe that when there’s contact between boats racing, someone has broken a rule. Not so. It’s possible for contact to occur, even with damage, without either boat breaking a rule. An answer to a question from John Shortman, of Brunswick, Ga., illustrates this fact.

In a dying wind, John and Joe were battling adverse current. Upon realizing he was losing headway to the current, Joe set his anchor. Soon thereafter John lost steerageway. Despite John having done everything he could to avoid Joe, the boats touched (with no damage resulting). There was no protest, but John and Joe disagreed as to who was in the right. A friendly wager ensued, with a case of beer bet on my answer.

In my opinion, despite the contact, neither boat broke a rule. Rule 45 permitted Joe to anchor, and as soon as Joe did so, Rule 22, and not the usual right-of-way rules (Rules 10 to 13), applied between John and Joe. Afer Joe anchored, Rule 22 required John to “avoid” Joe “if possible.” John did everything he could to avoid Joe. Therefore, it’s reasonable to conclude that it was not possible for John to avoid contact. So John did not break Rule 22.

Rule 14 applied to both John and Joe at all times. Its first sentence requires that “A boat shall avoid contact with another boat if reasonably possible.” Clearly, while anchored Joe could not avoid contact. For the same reason that John did not break Rule 22, he also did not break Rule 14’s first sentence. (Rule 14’s second sentence did not apply because, while Rule 22 applied, neither boat held right of way over the other, and neither was required to give the other room or mark-room.)

Considering the draw, I suggested the beer be sent to me, but it has not arrived.

There are other Rule 22 situations in which contact, even contact involving damage or injury, can occur without either boat breaking a rule. I’ll provide two examples. During a race on a river in England years ago, two boats on the same tack were close to each other running against the current. I was in the boat clear astern and was required by Rule 12 to keep clear. To minimize the adverse effect of the current, we were both sailing as close to the shore as we dared. The clear ahead boat abruptly ran aground and, despite my effort to avoid her, we collided. As in the anchoring situation, when the clear ahead boat ran aground, Rule 22 replaced the basic rule (Rule 12) and neither boat broke a rule.

Rule 22 also applies when a boat capsizes or has not regained control after capsizing. The rule states that a boat is “capsized” when her masthead hits the water. Therefore, if you capsize, Rule 22 replaces Rules 10 to 13 from the moment your masthead touches the water until you regain maneuverability after righting your boat. I witnessed an incident involving Lasers where a clear ahead boat with right of way under Rule 12 death rolled, placing her mast squarely in the path of the clear astern boat which could not avoid running over it. In this case neither boat broke a rule. However, if two boats on opposite tacks were running alongside each other and the port-tack boat death rolled, Rule 22 would not apply until her masthead hit the water. If the mast of a port-tack boat rolled onto the deck of the starboard-tack boat, the port-tack boat would break Rule 10. The lesson here is that, when sailing a boat that can death roll or broach in wild conditions, stay far enough from others so that, if you do roll, your masthead will not touch another boat before it hits the water.