whyte kinetics

Kinetics is a hot-button topic. There’s never been consensus about what is or should be legal, and more fundamentally, whether kinetics are a wholesome part of sailing or an unnatural act that should be banned outright. I won’t engage the argument in this space; instead I offer a few observations as a coach who has witnessed 30 years of kinetic technique in collegiate and Olympic sailing.

Kinetics can be broken down into three categories: the good, the bad, and the ugly. The good and bad are necessary complements in the competitive arena and I’ll focus on them. The ugly appear often, and that’s what on-the-water judging is for.

Good kinetic technique is essentially legal, it’s sensual, fun, and is an extremely sophisticated component of a successful sailor’s skill set. Bad kinetics are good kinetics done poorly. They are unsophisticated, mostly legal, feel terrible, and can be hugely frustrating. Ugly kinetics are illegal and are performed knowingly by sailors seeking an unfair advantage.

What separates the good from the bad? Let’s use downwind wave riding as an example. Successful kinetics enhance the natural action of wind and waves on the rig, foils, and hull. They do not replace natural forces. For best results, the natural stuff must be optimized before adding any kinetics. This is the first, and most important part of good technique, which I call “setting the table.” The second part is applying the kinetic force once the table is set properly. That’s called “time to serve.”

Setting the table

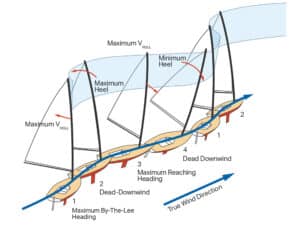

When it comes to wave riding, smooth, proactive steering is essential. If a boat is sailed downwind in waves with no steering, the boat’s speed will vary a lot through the wave cycles. The boat will often surf or plane rapidly down a wave then slow dramatically in the troughs as the bow gets stuck. Pressure on the sails builds when the boat slows, and pressure drops when the boat zips down the wave. The helmsman’s most important job is to smooth out the natural peaks and valleys with proactive steering. The challenge is to maintain a high average speed with the potential to boost the high average at the right moments to achieve launch speed. Once at launch speed, kinetics take over.

High average speed is roughly synonymous with maintaining stable pressure. The helmsman must be tuned into the pressure and steer to keep it stable, resisting the temptation to ride waves low too long with little pressure on the sails. Fast rides down the wave may be fun, but the boat often gets stuck at the bottom of the wave, loses speed, then feels a sudden pressure build on the sails. Boatspeed peaks down the face of the wave, and then plummets into a valley at the bottom. From this position the helmsman must either wait for the wave to pass or head up dramatically to get the boat going again. With proactive steering the helmsman is sensitive to the dropping pressure and is looking for a path of lower resistance so the boat does not slow excessively. The top speed may be lower, but the bottom speed, from which the boat can readily accelerate to launch speed with the next kinetic opportunity, remains much higher.

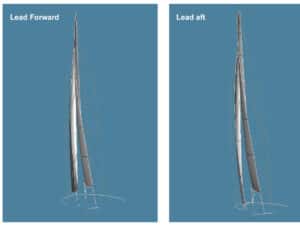

The team must work together to control the boat laterally. All extraneous lateral motion should be eliminated, but small changes in lateral trim should be associated with all of the steering. While a high average may be an adequate launch speed, usually a small power up is better and is achieved with a small course change, which should be initiated with a little leeward heel. Large power-up course changes are usually an indication of poor technique. Once powered up with slight leeward heel and at launch speed, the table is set and it’s time to serve.

Time to serve

Before pumping, hike into the heeling force to bring the boat level and to resist the additional heeling force that will come with the pump. Much of the time, hiking alone is better than pumping.

As you hike into the pressure you need to update your read on the kinetic opportunity and determine how to respond. If you determine a pump is appropriate, you have to be smooth. Smooth may sound like an oxymoron with kinetics, but it’s a perfect fit. While most kinetic actions happen quickly and include an intense application of force, it’s essential that the forces integrate smoothly into the existing state of motion. You need embrace the concept of smooth intensity. These two words really say it all.

Good kinetics connect smoothly to the stream of power propelling the boat, even if they are very intense. For this to happen there must be a transition at the beginning and end of the action. While these transitions are brief, it’s important they’re done smoothly. Trim through the pumps. They should start slowly, rapidly accelerate, and then slow toward the end. By trimming through the pump, the accelerating force lasts longer, giving the boat an opportunity to use the force to accelerate, and trim pumps are far less disruptive to the sails and foils.

It’s important to recognize that no pumping is faster than bad pumping. The key is to focus on quality not quantity. Minimize failed attempts by improving your table setting technique and be selective. If an attempt to reach launch speed doesn’t quite make it, then pass on the kinetics, stay with the high average, and wait for the next wave.

Assuming you’ve achieved launch speed, the boat will accelerate with the hike and subsequent or simultaneous pump. Resist the temptation to turn down the wave immediately. If the boat is still accelerating, don’t turn away from the pressure unless you are certain you’re on a path to maximize your wave ride. Too often, sailors turn down prematurely and end up stalling in the trough, after which the wave they were riding promptly passes by.

When in wave-riding (as opposed to wave-passing) conditions, your mission is to remain on the wave as long as possible. You must be aware of your path down the wave. The more you are sailing across the wave face, the faster you have to go to stay with the wave and vice versa. While staying high will assure better pressure and higher speed potential, you might still lose the wave if you sail across the face too much. Most of the time the waves are asymmetric from jibe to jibe, so the optimum steering range varies.

If you are in wave passing conditions, your mission is to pass the wave ahead as quickly as possible, regardless of the how high you need to sail. Recognizing that you have the potential to pass waves is critical because you will need much more power to pass waves than to ride them. The boat needs to remain fully powered as you accelerate so that you will have both the speed and power to pass the next wave.

OK, that was a mouthful, and there is at least a full meal of kinetic technique on the table. Remember to focus on quality over quantity and always be smooth.

Pro Tip: Many Rule 42 penalties assessed by on-the-water judges are for ineffective actions. Poor technique is usually more provocative, often has a negative effect on performance, and can easily earn a penalty. The most effective technique in the majority of situations is perfectly legal. It is measured, efficient, and in harmony with the natural action of wind and waves on the sails, foils, and hulls.

Kinetics Sampler Platter

Many sailors assume that pumping and rocking are unskilled jobs that succeed primarily through brute force with little technique or finesse. Nothing could be further from the truth. Successful kinetics help minimize the negative effects of the extra mass of the crew on the boats performance in underpowered conditions. Just as a horseback rider learns to allow the horse to move beneath the rider, sailors learn to allow to the boat to move beneath them so the boat doesn’t have to do as much work. In my April 2010 From the Experts column (“The Truth of Kinetics”) I referred to my concept of “setting the table,” for kinetics, and then “serving.” Here are some specific examples.

Good table setting

Smooth, proactive steering

Maintain high average speed

Allow the boat to accelerate as prime pumping moment approaches (power up)

Keep helm balanced

Boat level or bow down

Sails pressured and stable

Sailors positioned to hike into the pressure that will be created by the rock or pump

Bad table setting

Reactive, rough steering

Boat speed spiking and crashing through the wave cycles

Pump when boat is slowest with bow in wave and sails heavily loaded

Helm loaded boat heels to leeward with increasing pressure, and sailors not responding to the boat’s messages

Boat on backside of wave and bow up

Sails either over or under-pressured

Good serving technique

Hike into pressure before pumping

Trim through pumps

Measure the pump to the load. Don’t overdo it

Maximize accelerate before turning down (or don’t turn down at all)

Pump with boat level or bow down

Bad serving technique

Allow boat to heel to leeward as pumping force is applied

Jerky, staccato pumps

Always pumping as hard as possible

Turn down the wave as soon as acceleration is felt

Pumping uphill