Improve Your Odds in a Protest Hearing

No matter how well you know the rules, or how conservatively you sail, eventually you’ll end up in a protest hearing, either because another boat is protesting you or because you, acting as you should under the Basic Principle, Sportsmanship and the Rules, have protested another boat for breaking a rule. Should you end up in the room, however, there are steps to take to improve your chance of success in a protest hearing.

You can improve your odds even before an incident takes place. If you are on a converging course with another boat, hail loudly to make your understanding of the situation and your intentions clear. This might help you avoid a trip to the protest room altogether. Doing so will also call the attention of nearby boats, thereby improving your chances of having witnesses. If you have the right of way, indicate with a hail. If you must keep clear, hail to indicate that you intend to do so and how you’ll do it.

To protect your right to protest, you must promptly hail “Protest” afer the incident and, if your boat is over 6 meters (19′ 8″) in length, display a red flag. The rules do not allow much delay in displaying a protest flag. Remember to comply with any additional protest requirements stated in the sailing instructions. The most common of these are a requirement to notify the race committee of your intent to protest at the finishing line and to write the written protest on a specified protest form.

Your written protest need only identify the incident, including when and where it occurred, and be delivered to the race office within the time limit for protests. You must identify the boat you are protesting, either on your written protest or in some other way, before the hearing begins. If you take all these steps, your protest should be found to be “valid” at the beginning of the hearing. If the incident resulted in damage or injury that was obvious to the boats involved, then the requirements to promptly hail “Protest” and display a red flag are waived, but you must later “attempt to inform” the boat you are protesting before the time limit for protests.

Time spent preparing for the hearing can increase your odds of winning a protest. Gather witnesses that saw the incident, have a rulebook available, and, if possible, a copy of the Case Book and U.S. Appeals. Review the incident with your crew, then study the rulebook to find the applicable rules and, if there’s time, look for ISAF Cases or US SAILING Appeals that support your argument in the protest room. The protest committee must allow you “reasonable time” to prepare.

It’s likely no one on the protest committee saw the incident, and some or all of the protest committee members will probably be unfamiliar with how your boat handles and with what the wind, wave, and current conditions were on the course at the time of the incident. Their job is to take evidence from the protestor, protestee, and their witnesses, determine from the testimony the relevant facts, and only then make a decision based on the applicable rules.

While the parties are present during the hearing, there should be three distinct phases: consideration of validity, taking of evidence, and a summation period during which you and the protestee are given the opportunity to argue why the decision should go in your favor. If you took the steps I described on the water and on shore before the hearing, your protest should be found to be valid during the first of these three phases.

During the fact-finding part of the hearing, you will have opportunity to present your testimony and the testimony of your witnesses. Speak clearly and without using jargon and provide as much credible testimony from yourself and your witnesses as you can that supports the critical facts as you saw them. If a witness’s testimony calls your testimony into question, then, to the extent possible by questioning that witness, show how the witness might be in error because of his vantage point of or distractions he was facing.

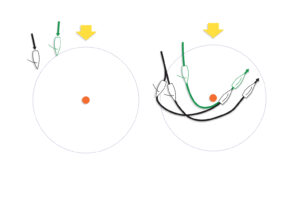

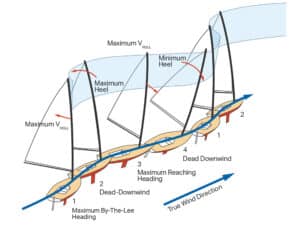

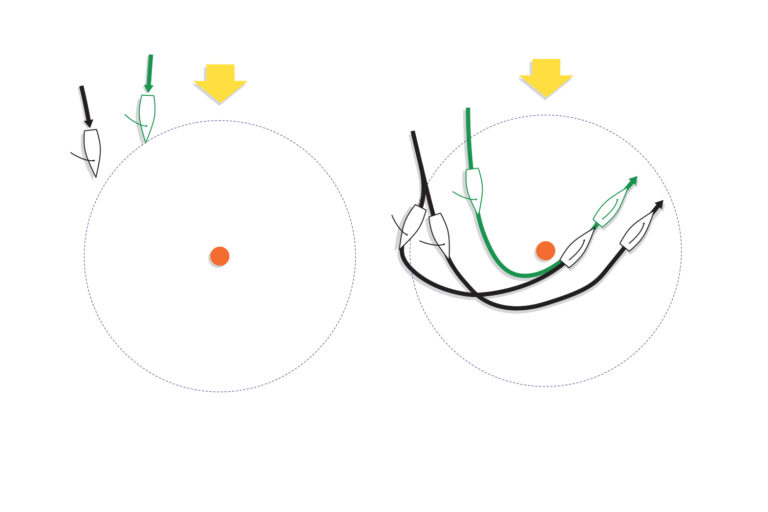

If you’re asked to move models to show the positions of boats before and during the incident, work methodically through the incident, making sure that all members of the committee and your opponent can see each time you position the models. Start with the positions of the boats a few lengths before the incident. Paint a picture by describing the wind, the seas, the current, your approximate speeds, and any special conditions caused by changing sails, gusts, hails, or sources of noise or distraction. As you move the models, make the motion consistent with the wind direction and the current, and move them in a way that is consistent with their scale. Often the spacing between boats is crucial. If you think there was 5 feet between you and your opponent at a particular moment, and if you were sailing 15-foot dinghies, then position the models so the space between the two boats is about one-third of their length.

When it’s your turn to summarize, state why, given the testimony, the committee should find critical facts and why, given those facts, the rules imply that the decision should be made in your favor. Tis is the time to go into detail about which rules you believe are applicable, how you complied with those rules, and how your opponent did not. If there are relevant cases or appeals that support your argument, this is the time to point them out. Don’t try to teach the committee the rules, but point out the rule numbers and the defined terms that you think are critical to the decision.

Afer the summation, the parties are dismissed while the committee decides on the facts and makes it decision. After the parties are called back in to hear the decision, if the decision goes against you, spend a few minutes with your crew reviewing the facts found and how the committee applied those facts and the rules in reaching its decision. Even then, there are still steps you can take that might reverse the decision. If you believe the protest committee made a significant error, you may, within 24 hours of being informed of the decision, ask the protest committee to reopen the hearing. If new evidence becomes available within that 24-hour period, you can use that as the basis for requesting a reopening. Unless the right to appeal is denied under Rule 70.5, you may appeal the protest committee’s decision or its procedures, but not the facts found. To appeal, you must request a written copy of the protest committee decision within seven days of being informed of the decision. Afer you receive the written decision, you then have 15 days to send your appeal to US SAILING.

**Pro Tip: **After an incident, note the sail numbers of nearby boats. On a larger boat, ask a crew member to write the sail numbers somewhere on the boat.