Rich Wilson

The Vendée Globe, the greatest solo ocean race on the planet, is starting to wind down with the survivors sailing one by one across the finish line in the wake of Francois Gabart Macif. But if you are waiting for an American sailor, don’t bother. This year, there aren’t any. In fact, most years there aren’t any. Vendée sailors like to point out that more humans have summited Everest, and orbited Earth, than have sailed solo and nonstop around the globe. It’s an elite group, for sure. But an even more exclusive club, sadly, is the number of Americans who have officially completed the Vendée Globe. That number is two. Yep, just two, Bruce Schwab, 2004-’05, and Rich Wilson (at right), ’08-’09 (Mike Plant raced in the ’89-’90 edition, and completed the course, but had been forced to retire after receiving outside assistance off New Zealand).

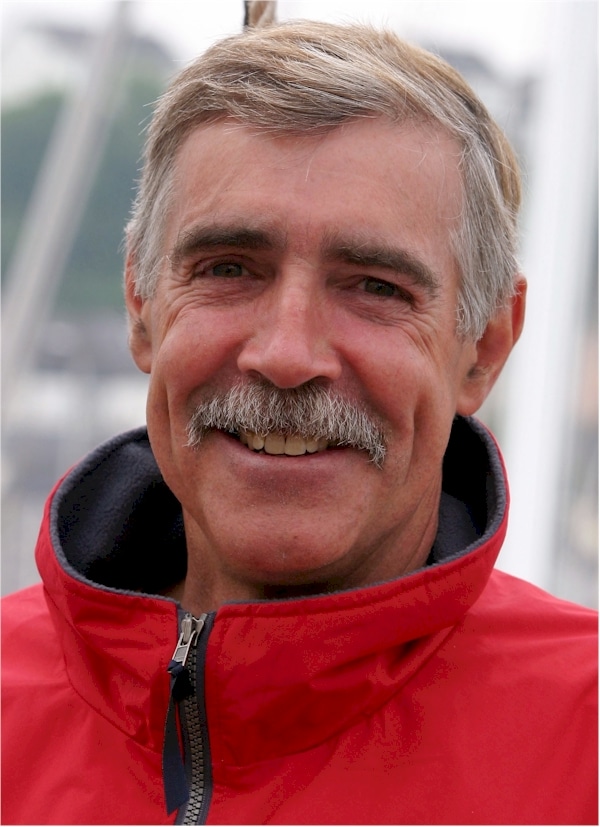

Wilson, who previous to the Vendée Globe was best known for attempting record passages aboard a series of multihulls called “Great American,” is in an especially unique category (in fact, he is the only member): Americans who have completed the Vendée Globe at the age of 58. Here he is, before the start:

Wilson set sail from there and didn’t exactly threaten the leaders, finishing in 121 days to winner Michel Desjoyeaux’s 84 (logs, photos, videos, and much more

from Wilson’s voyage, which was followed by schoolkids via his non-profit, sitesALIVE!, can be found here). But he did beat two other boats that finished (and 19 that retired), so his voyage is nothing to scoff at. That is even more apparent when you read Wilson’s account of his Vendée campaign: Race France to France: Leave Antarctica to Starboard.

It is a workmanlike account of Wilson’s entire Vendée campaign that does an excellent job of conveying the sheer superhuman effort required to race an Open 60 nonstop for months on end–fighting asthma, injuries, storms, the relentless grinding pedestal (Wilson counts how many turns are required for each maneuver), and stress. Wilson also captures the reasons sailors endure the above–the satisfaction of pulling off an epic challenge, the connection to the ocean world, the thrill of man and boat in harmony, and the beauty of the unique camaraderie and intense bonds that develop between the sailors.

I don’t know who the next American to race the Vendée might be (though I suspect we will see this guy at some point). But for any Vendée aspirant or fan, Wilson’s book is required reading, in part because the genre of first-person, American Vendée accounts is so slim. To hear more about his voyage, I recently caught up with Wilson.

TZ: You thought about and prepared for the Vendée for years. What about it, if anything, surprised you?

RW: I thought about sailing the Vendee Globe only after the Vendée Globe in 2004. I had followed it since it began, but never had any interest in it until we began to think of the global K12 possibilities for sitesALIVE! of that uniquely global event. I got the boat in March 2006, and prepared her, along with developing the sitesALIVE program, for the 2.5 years until the start.

“Surprise” seems to suggest something unanticipated, and I wouldn’t want to apply that to my following remark, as I had no data basis for it one way or the other. Perhaps what I loved the most about the Vendée Globe 2008-’09 was the extraordinary and warm reception given to me and our team and our group by the French–from the sailors, to the vendors, to the race organizers, to the media, to the general public. Across the board, without reservation, France welcomed the sole American team, and warmly. That was the best part of the whole experience.

TZ: What was the highest moment for you during the race, and the lowest?

RW: I’m not sure there are specific highs and lows, perhaps there are plateaus. The race was 2904 hours for me, so there were dozens of high times, and dozens of low times. High times are the birds, skies, flying fish, encouraging emails from competitors, chats with Jonny Malbon in the Indian Ocean, Andi on Radio Vacances, friends at home, watching the extraordinary sailors at the front of the fleet, marveling at the camaraderie of the solo sailors, and the 100% use of all my faculties. Furthermore, in the instances of Yann Elies’ injury and Jean Le Cam’s capsize (and Vincent Riou’s rescue of Jean), seeing the upholding of the tradition of the sea “to go to the aid of a mariner in distress”. Those stories should be told at every level of sports in America.

TZ: You sailed the race at 58 years old. If you were a younger man, could you imagine racing the Vendée two or three times like some of the French sailors?

RW: The race is beyond physical. I felt at the end that I should go play for the Patriots in the Super Bowl, just to take an afternoon off. So I applaud those who go back for a second or third or even fourth time.

TZ: What did you like and dislike about the Open 60? How do you compare it to racing a multihull?

RW: Open 60s don’t like to sail upwind, at all. Plus they heel, which the multihulls didn’t, so the monohull is far more fatiguing than the multihull.

It’s impossible to read Wilson’s book and not wonder whether you would be capable of a similar voyage (my honest answer is that I doubt very much that I could pull it off–though I could imagine getting to the top of Everest with a guide). One moment that lures us all in, though, is a racing rounding of Cape Horn. Here is Wilson passing into the Atlantic, and he seems pretty happy about it.