if conditions warrant, some boats, like J/70s, FJs, Collegiate 420s and Snipes, successfully wing for the entire run. And for other boats that carry asymmetric spinnakers, such as J/105s and Melges 20s, brief moments of winging can present gains, such as when jibing, (a late-main jibe), coming into a leeward mark gaining an overlap, or shooting the downwind finish line. It’s a powerful technique to have in your toolbox these days, so let’s dive deeper into the art of the wing, how to do it and when to do it.

There’s usually no question when in the middle wind ranges—from 8 to 14 knots—where the wing technique works well. By doing so, you’ll sail less distance without sacrificing much speed, getting you to the leeward mark sooner than someone who reaches back and forth. But in light air, it’s often too slow to wing, and the jib or kite doesn’t have enough pressure to fly well. Also, when the wind is light, the main falls into the middle of the boat, causing an unintentional jibe. You need enough pressure to hold the sails firmly in the winging configuration to make it work.

In the crossover zone, when you are unsure if winging will work, it can pay to give it a shot. If it doesn’t feel powered up and fast, abort the wing by continuing your turn, jibing the boom, and flattening onto the new jibe. The cool thing with this move is that you can get a boost of speed during the flatten, especially in a dinghy. Experiment with winging in the crossover wind range, then aborting, making it a late-main jibe.

At the other end of the spectrum, when it gets super windy, boats like the FJ, 420 and Snipe are still winging and might even plane on the wing. For heavier boats that wing, like the J/70, there comes a time to abandon the wing and start planing on the reach. It’s all about your best VMG to the mark, knowing your boat, and understanding when to transition as the breeze changes. In puffy conditions in the planing crossover range, 14 to 18 knots, the true masters of downwind morph from one mode to the next, putting hundreds of meters on the competition.

When winging, you must have a big lane behind you because winging is difficult in bad air. Also, boats behind you that are also winging throw a big wind shadow. Always work to find a nice lane before winging. Some people call this a seam in the fleet, a corridor of nice pressure with no boats behind you.

Winging Angles

For those unfamiliar with winging and the angle changes created by doing so, one way to think about it is to compare it to a symmetric spinnaker boat, such as an Etchells or Lightning, that can square the pole back in a medium breeze. In light air, those boats reach back and forth with the pole near the headstay. Once the breeze increases enough, they square the pole back and sail deep. This is a similar angle to winging. A boat with the spinnaker squared back is basically the same as being wing-on-wing. When in this mode, you’ll jibe through about 20 to 30 degrees.

I always look forward, toward the gate marks or finish line, to determine if I am sailing the least distance. Visualize your new angle if you were to jibe and question whether it would be closer to the mark. If so, and the lanes are free, do it. Usually when winging, I want to see the leeward mark right over the bow or just between the jib or spinnaker and the mainsail. While doing this, let’s say you get a lift. The jib or spinnaker suddenly feels less powerful, so you head up to get to the optimal angle again with the sheets pulling. Now the gate or finish line has dropped out of your field of vision, behind the main. That tells you it’s time to jibe. Conversely, if you get a big header while aiming at the gate and now appear overstood, abandon the wing and go back to a reach. The key is to point the boat at the gate or finish line in whatever configuration you need to be in for the given wind conditions, assuming you have a good lane.

Tactical Winging

A key to sailing well downwind in any boat is to satisfy two basic rules: Sail the jibe that takes you most directly toward the leeward mark, and sail in the most breeze. If you can sail toward the mark while in nice pressure and in a big lane, you’ll hit a tactical home run. When you are in a boat that has various modes, like reaching and winging, always use the most appropriate mode to help you. Here are a few examples:

A. You round the weather mark in a left shift and want to go straight downwind on the header. It’s blowing 10 knots, so winging will provide the best VMG. After rounding the weather mark, you reach for a bit until a lane opens up. Now you have to decide which jibe to be on while winging. You could simply wing on the starboard jibe, or jibe over to port and then wing. Because you are headed and happy, the correct move is to simply bear away and wing, staying on starboard.

B. You round the weather mark in a lift, so the game plan is to jibe to port. But there’s a cone of bad air at the top of the course. You reach for 30 seconds to a minute, eager to jibe and go the other way. With a train of boats sailing straight out of the mark with you, winging away would put you in bad air. So, the best move is to jibe onto a port reach to quickly exit the train of boats and their dirty breeze. Once clear of the bad-air zone, let’s say 50 to 100 meters, go into winging mode to sail the header toward the leeward mark on the port jibe. You’ll be in a nice lane, sailing low and fast toward the leeward gate.

C. You’re leading a tight race or might be just ahead of a group of boats, and you round the weather mark. Don’t immediately wing. If you do, you’ll likely get covered. Here, the move is to round the weather mark, reach for a while, and be patient. Once the boats behind you wing, then you can establish a nice lane and wing. If you reach for a while and feel like you should be winging, but no one around you is, and you want to get away from nearby boats, jibe to port, as mentioned earlier, reach for a little bit to get away from the group, and then wing into a nice lane.

D. If you round the weather mark in a lift and have no boats to worry about behind you threatening to steal your wind, a technique unique to the J/70 is you can get into a wing by bearing away and slowly jibing the boom. It allows you to quickly sail the other way downwind, as if you had completed a full jibe and then winged the kite. On smaller boats that accelerate more during maneuvers, it’s faster to jibe, flatten, and then wing the jib.

Practicing and Speed

Winging well takes practice and communicating to your team about the next move. It’s key that everyone is on the same page. With all the tactical options in the J/70, the fleet has developed its own lingo about turning while winging, “left turn 1 degree here” or “right turn 1 degree,” because up and down can get confusing with sails on both sides of the boat. For winging or exiting the wing in a J/70, identify the sail you are jibing. For example, say, “jibing boom to a wing,” “jibing kite to a wing,” or “exiting wing with boom over and a left turn.” In small boats, it’s a little more straightforward, but communications need to be defined regardless. A few examples are: “Let’s wing here,” “let’s jibe then wing,” and “let’s do a wing-on-wing jibe.” And to exit the wing, “jibing the boom to a reach.”

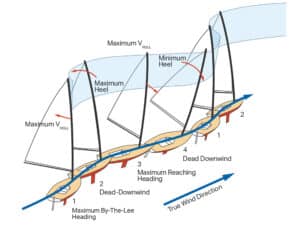

Sailing fast while winging is critical, so let’s discuss what you should focus on. The short version is, once you have winged a jib or a spinnaker, sail slightly up toward the jib or spinnaker on a broad reach, or a “high wing,” as some call it. You’re trying to not sail dead downwind because it’s faster to be slightly up toward the forward sail in a high wing. There’s a sweet spot, which is where the sail would want to fall in toward the boat and assume a reaching position, if you were to head up a few more degrees toward the jib or spinnaker. If you see that happening, bear away a few degrees until it’s stable and happy. At that angle, the jib or spinnaker will be powered up.

If you’re holding the sheet, you can feel the sail pulling nicely. Bear away a few more degrees to a dead downwind angle and the sail will lose a little pressure. Bear away a little more and you will feel the slowest winging situation possible—by the lee where the sheet pulls the least because the main starts covering the jib or spinnaker. I see a lot of kids doing this in the FJs and 420s, and sometimes adults in the J/70s. You can end up there by turning down accidentally, having a wave push the bow down, or possibly by a windshift lifting you. To avoid sailing too low or two high, stick to the rule of sailing high on the foresail, but not so high that it wants to collapse in on itself. This powered-up mode is fast. To keep it here, you need to constantly test the ups, look at the telltales and masthead fly, and feel the power in the sheet.

If you are at the perfect wing angle and notice a lift (the masthead fly goes from the weather corner of your boat to the center of the stern), the sheet loses pressure, or you just feel like the boat has lost pressure, head up if you want to continue straight. Or immediately jibe to a reach, throwing the boom over, flattening with extra speed onto a header, then bear away and wing again. The jibe maneuver when lifted is super-fast and allows you to quickly sail the header downwind. If performed before others around you, it allows you to lead on the new, long, headed tack. All of this is tactical gold.

Now that you know how and when it’s best to go wing-on-wing, let’s explore seven top winging moves that can make your race.

Cut the corner. Typically, everyone sails out of the weather mark on starboard, reaching, unless conditions call for an immediate jibe set. If you can wing before the boat in front of you, you cut the corner on them and still maintain a starboard-tack advantage. The boat in front ends up in a difficult situation in that they want to jibe to aim for the gates, but you have borne away inside them and cut them off, and you’re still on starboard. I love using that move in a J/70. I’ve been passed by it, and I’ve passed boats using it.

Be the first to wing. If you round the weather mark with a big enough lead or a gap behind you and instantly wing, you can gain huge on the boats that have not yet done so. Doing that while leading can instantly break the race open. While others are reaching and waiting for the opportunity to wing, you’re already sailing deep, headed straight for the leeward mark, and you’re gone. You can end up winning the race by hundreds of meters. And if you happen to have a gap behind you, winging before the group ahead allows you to cut the corner on them.

Paint the competition into a corner. In the same realm of cutting the corner, this move occurs in the corner, near the layline. Let’s say you’re going downwind, reaching on port jibe, and following someone who is also reaching. As you approach the left corner (looking downwind), knowing they will jibe soon, wing behind them. Now you’re sailing deeper and cutting the corner. When they jibe, you now have a perfectly matched racing setup to jump them and steal their breeze. As the boats converge, watch their masthead fly to see where their wind is coming from, and then jibe over by simply throwing your boom with a right turn and flattening onto their breeze. It’s a quick move and takes the wind out of their sails, literally and figuratively. From here, either you roll them, or they’re forced to jibe back into the corner, reducing their options and forcing more maneuvers. You can also “paint into a corner” against groups of boats.

If in the back of the fleet, wing immediately. Another time to go right into the wing mode is when you’re doing poorly. Maybe you were OCS and went back now to find yourself in last place, desperately hoping to catch up. Wing-on-wing can give you that opportunity. Once rounding in last, you can always lighten the mood by pointing out the good news of having a massive lane, and then instantly wing. I’ve seen a lot of people in that position catch up a ton downwind just by getting into the wing and keeping it the whole run, sailing less distance.

Sail perpendicular. When coming into the finish line or a leeward gate, sail perpendicular to reduce distance. By winging, you cut the corner on any boats ahead that are reaching. I think of it as sailing one side of a triangle while they sail two, by extending forward, jibing and reaching back. You can get to the finish line sooner with this move, even if the wind is a little light to wing.

There is also a specific scenario coming into a gate where you can use it to get room. If you are closely trailing an opponent and both of you approach the gate just outside the zone (aiming at the middle of the gates), you can wing behind them toward the mark to enter the zone first while they extend forward, then jibe to head back and round the gate. You are now inside and have room. Their jibe opens their stern, and you have entered the zone first and inside. This doesn’t happen often, but it feels nice when it does. It leaves you in a much stronger rounding position to start the next leg.

Ping the competition. You’re on the port jibe near the layline, approaching the right-hand gate (looking downwind), and there are other port-jibe boats overlapped to your right. They’re going to have room on you, probably leaving you on the outside of a big pinwheel around the gate mark. In this situation, you can jibe to starboard and reach toward those boats to take them out past the layline, then lead them back clear ahead and rounding ahead. Chances are, they might not anticipate you doing this, but even if they do, they have to stay clear. For safety within the rules, do this well before the three-boatlength zone, maybe as far out as five or six lengths so there’s no question you’re outside the zone. The boats you’re reaching toward can even be winging on the starboard jibe, but they have to either head up or jibe if on port because you’re the leeward boat. In a classic match-racing move, you’ve reached them off the racecourse, forcing them to overstand. They’re typically flailing at this point and probably starting to yell; bear away once you feel the geometry is correct and jibe toward the mark, breaking the overlap with them and entering the zone clear ahead. We call this the ping move. It can also be done at a downwind finish line.

Vary modes to manage your lane. If you’re wing-on-wing and someone is sailing at a different angle, about to encroach on your breeze, go into reach mode until you find another clean lane. Then bear off and wing again. If you maximize your time in big seams or lanes, you can do some damage downwind.