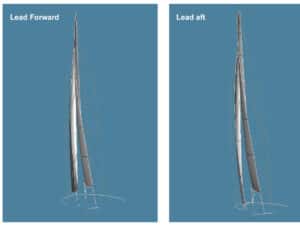

A big piece of the “speed loop” that’s often overlooked, especially in smaller boats, is rudder angle. I was recently chatting with main trimmer Warwick Fleury about_ Alinghi 100_, the winning boat in the 32nd America’s Cup. They sailed this boat when it was new for some time thinking it was perhaps not a step forward. Then one day, they put up a jib that was built for a different rake than the normal rake. All of a sudden, the boat started winning speed tests and eventually won the Cup. We had a similar situation at Luna Rossa with an older boat. Everything possible had been tested, from rudders to keels and masts to structures. It was not a very fast boat. Then we moved the mast forward a few inches, and the boat came alive. The gain from getting the balance correct was bigger than anything else we tested.

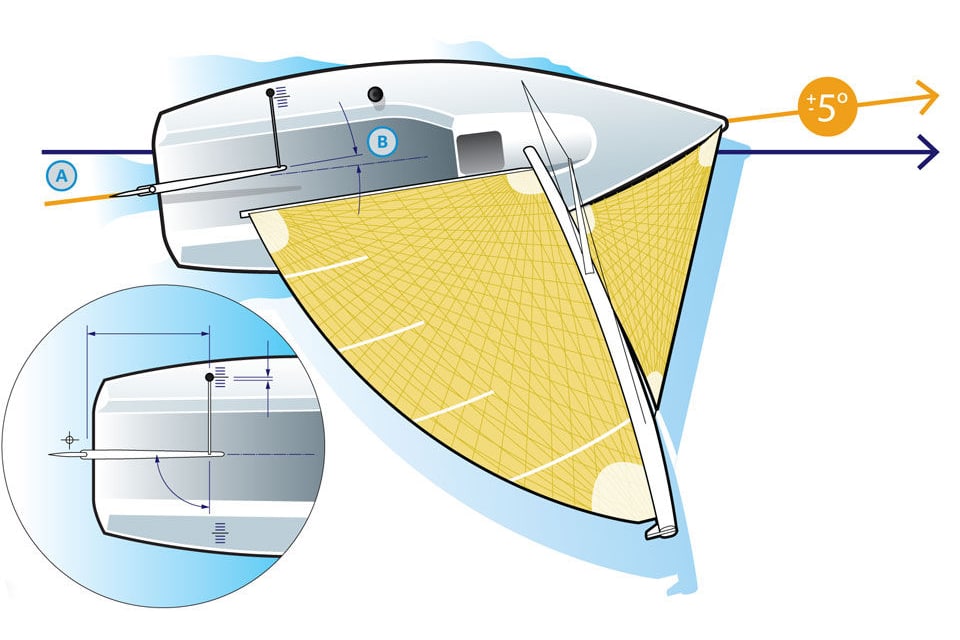

So amid such talk about optimum rake for various boats, how can you tell when you’ve really nailed it—that it’s just right? The answer can often be found in the amount of helm you’re carrying. In very general terms, you want to sail upwind with an angle of attack of about 5 to 7 degrees. The angle of attack is the sum of your rudder angle and the amount of leeway you’re making (see diagram). The more leeway your boat makes, the less rudder angle you need. Conversely, the less leeway your boat makes, the more rudder angle you need. Regardless, the combination of those numbers should be around 5 to 7 degrees. For example, if your boat slides through the water with 5 degrees of leeway, you should be carrying about 2 degrees of rudder angle. Boats such as Melges 32s, Farr 40s, and J/24s make a lot of leeway, so they’ll carry minimum rudder angle. At the other end of the spectrum, an Etchells, with its skeg, or a Star, with its hard chines, make very little leeway and, as a result, will carry at least 5 degrees of rudder angle.

How much leeway does your boat make? It can be tough to figure this out; you can measure forever and still not account for things such as current, waves, boatspeed, and angle of heel. Since you’ll probably never come up with the exact number, the best you can do is work in general terms—does your boat make a lot of leeway or just a little? A good starting point is to note how you have to approach the windward mark. Can you tack right on the layline, point the boat at the mark and make it, or do you have to sail on the layline with your bow pointed above the mark to fetch it? If there is no current, use a GPS and make some runs at a mark. Checking your COG (course over the ground) versus your heading will also give you an idea about your boat’s leeway.

Once you have a sense for the amount of leeway your boat makes, the next step is to find out where the tiller is, relative to the boat’s centerline, when the rudder is lined up with the keel or centerboard. Just because the tiller is centered, don’t assume the rudder is, too. I’ve found that the tiller will almost always be off to one side or another. With a Star or an Etchells, you can pull the boat out of the water and put a straight edge along each side of the skeg and aft over the rudder. Then measure the distance from the trailing edge to the straight edge on each side of the rudder. If your boat is in the water or does not have a skeg, find a day with smooth water and no wind. Motor the boat to full speed, shut the motor off, raise the motor shaft out of the water, and just drift. With the crew in the middle of the boat, the boat should track straight when the rudder is straight. If the boat doesn’t have a motor, you can tow it quickly, keeping the boat out of the towing vessel’s prop wash. Then release the towline and drift to achieve the same results.

Once you know where the tiller is when the rudder is centered, you can create some benchmarks. With the tiller locked in the rudder-centered position, rotate the tiller extension so that it is 90 degrees from the tiller. Put a mark on the tiller extension (if its length is not adjustable, use the end of it) and then put a corresponding mark on the side of the deck, directly under it (see diagram inset). Using some basic geometry, you can put marks indicating 0 to 7 degrees of rudder angle. To determine the distance between each degree mark, multiply 0.017 by the horizontal distance from the center of the rudder pivot point to the center of the mount for the tiller extension—aka the effective length of the tiller. For a 36-inch tiller, each mark will be 0.63 inches apart. Now you have some reference points for determining whether or not your boat is balanced, and you can make adjustments to your rig setup from there.

It’s helpful to know your rudder angle in situations other than when sailing upwind. Whenever you’re accelerating out of a tack or accelerating on the starting line, you need to have your rudder on, or close to, centerline. You can use the marks you put on the deck to confirm its location. Often on the starting line, you’re head to wind, and you bear away by pulling the tiller toward you, which is fine; you have to do that. You end up at a broad angle—this is where the mistake is commonly made—and, as the boat accelerates, you start turning the boat up to closehauled with the rudder. When your rudder is pushed to leeward, its angle of attack is 0 degrees, so it’s basically just sliding through the water, not generating any side force or lift. All the lift is coming from your keel. If your competition next to you is able to keep their rudder generating more lift than yours, they will accelerate faster than you. The same is true when coming out of a tack. You’re making a similar turn up to your new course and want both the keel and rudder to generate lift.

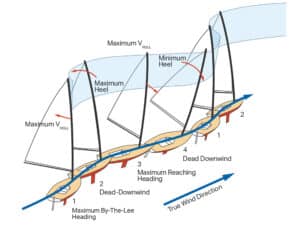

Even downwind you want some positive helm, especially if you’re not sailing dead downwind. Any time you’re hiking or planing on boats with asymmetric spinnakers, you’re generating side force. So you need to generate lift to counteract that and transform that side pressure into forward speed. Watch where your tiller extension lines up with the deck marks to quantify the amount of positive helm you’re using.

This article originally appeared under Boatspeed in the November/December 2012 issue of Sailing World.