I recently sailed two J/24 regattas with current national champ Will Welles. At Midwinters, he drove while I called tactics. We switched roles at the Sperry Top-Sider St. Petersburg NOOD. When Will drove, he was relentlessly prodding the crew to balance the boat. Then, when it was my turn, he was constantly moving his weight around and asking me how my helm felt. Until that regatta, I mistakenly thought I’d been doing a good job working the boat. Now I’m aggressively working my angle of heel—with great results.

We often use the phrase, “sail it flat,” and occasionally I do sail my Thistle absolutely flat, but mostly I race any boat with at least some heel. A better phrase should be, “sail it balanced.” A balanced J/24 or J/22 might have 10 degrees of leeward heel, while I might heel my IC dinghy 2 degrees to windward to get it to feel right. Each boat is different; fortunately there are simple ways to understand which angle of heel works best for your boat.

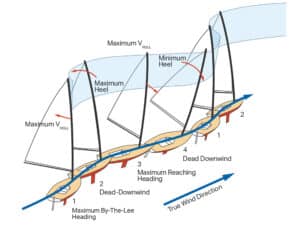

Whatever your best heel angle may be, keeping it constant is important because as your foils move through the water they’re creating lift. Any change of heel causes your foils to swing from side to side through the water, jeopardizing this precious lift.

Balanced (above)

1 Sail trim: The boat is balanced by easing and trimming the sails.

2 Rudder Angle: With everything in balance (crew, sail trim, and heel angle), the rudder should trail freely behind the boat without drag; note the straight tiller and even exit of the wake.

3 Crew Postion: The crew is at maximum hike.

4 Heel Angle: The boat is flat, and the sails are powered up, a perfect setup for the flat water and wind strength.

Find your angle

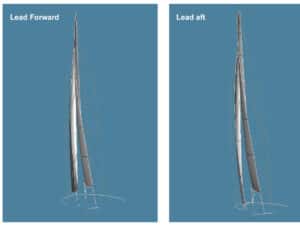

The optimal constant heel angle for any boat is easy to find. One way is to find the heel angle that gives a neutral helm. Neutral helm is when you don’t have to constantly pull or push the tiller to make the boat sail straight. When the helm is neutral, the centerboard or keel is generating all the lift while the rudder follows effortlessly behind. In my Thistle, for example, my helm is absolutely neutral at zero degrees of heel in flat water. The Thistle is designed to sail flat because the weight of the centerboard doesn’t contribute much to the boat’s righting moment, and sailing flat keeps the centerboard at a vertical—and efficient—position.

If I sailed my J/24 or J/22 flat, for example, I would have to constantly push on the tiller. So instead, I induce a little leeward heel to get that same zero-helm feel. Most keelboats are designed to have a balanced helm when heeled in heavy wind, to take advantage of the keel’s righting moment. In light air, we need to artificially induce heel to maintain balance. Regardless of the boat I’m sailing, I know I have the balance right when I can let go of the tiller and the boat continues in a straight line.

Neutral helm is best approximately 90 percent of the time. In the Thistle, we know a few degrees of heel works best in chop. Being perfectly flat causes the boat to slap into the waves, so when sailing in chop a light tug on the tiller is good. In heavy wind in the J/24, I heel up past neutral helm in order to swing the keel out a little, giving me more righting leverage. Heeled in this manner, I do feel a little tug on the helm. Conversely, in flat water and medium wind, I sail the J/24 flatter than neutral helm, actually pushing lightly on the tiller, it feels terrible, but it’s fast. In our J/22, I almost always have a little windward helm because we get just enough lift from the rudder to make up for the leeway caused by heel. Whatever boat you sail, neutral helm is the default, but always explore a few variations one way or another.

Steady as she goes

Once I establish the ideal heel angle, the next step is keeping it constant. Maintaining the same angle of heel when not overpowered is done mostly with crewweight placement. In these conditions, I’m trimming the sails to the correct trim for that boat. Defining “correct trim” is beyond the scope of this article, but it’s important to realize that this trim is independent of heel. In light to medium winds, for example, in the J/24 or J/22, my jib trimmer and I focus on making sure we are trimmed correctly, while the rest of the team continuously adjust weight placement to keep the boat at a constant angle for the given conditions. There are a lot of ways the team can make this work; we move crew weight around most efficiently when the team is talking amongst themselves, leaving me to focus on trim and steering.

Controlling heel angle when overpowered is completely different; it’s done primarily with sail trim. The Thistle has a huge main; we are at max hike in about 9 knots of breeze, and we are hiking just as hard in 18 knots. Through the entire range, we adjust the sails to keep the boat balanced, trimming in the lulls and easing in the puffs, all while fully hiked. The J/24 genoa is big; for puffs we ease it as often as the main, and then we trim in both sails for a lull. I usually have my hand on the genoa winch handle and grind it in before I pull in the main. I also pull on the backstay in a puff in the J/24, and ease it in a lull, and occasionally I will play the traveler. Adjustments will vary from boat to boat, but the overall concept is universal; once we are already hiking, we constantly adjust our sails to keep that constant angle of heel.

Once I’ve established the ideal heel angle for a boat and conditions, I’m willing to modify my constant-angle-of-heel rule in order to help steer the boat. If I want to head up, I use leeward heel, and to bear off, I over flatten the boat. In lighter winds, I steer by using crew weight movement to heel up or flatten, just as we would in a puff or lull. And in heavy winds, we continue to hike full, but steer by easing or trimming. Steering by changing the heel angle reduces rudder movement, and thus is fast. Communication to the driver and trimmer is critical. For example, the forward crew will countdown a puff (or lull) with, “Puff (or lull) in 3, 2, 1, puff on.” And even better, they may even put some qualifier on it, like, “Big puff, looks like a header, in 3, 2, 1, puff on.”

Unbalanced (above)

1 Sail trim: The main is eased a little and should be

constantly adjusted to maintain balance.

2 Rudder Angle: The boat is out of balance, resulting in

weather helm.

3 Crew Postion: The crew is at maximum hike.

4 Heel Angle: Since the crew is already at max hike, the main should be eased more to flatten the boat.

Anticipate, don’t react

When we’ re on our game, we anticipate the change and make the adjustments as it happens. In lighter winds, if I hear the countdown, I expect my team to start leaning out a little more just before we hear, “Puff on.” But, if we’re already hiking full, and I hear “puff in 3, 2, 1,” I would expect no movement from the team. Instead, my trimmer and I will start easing our sails an instant before the puff hits.

Feedback from the driver is equally as important. With the helm in hand, I’m the first to feel if the boat is off neutral, and I immediately let the crew know. When there is a transition between fully hiked and not, they need to know if we are in the new mode, but I’m the only one on the boat that knows exactly when that happens. When the wind builds enough that I need to start depowering, I say, “Full-hike mode.” When I say, “Fully trimmed,” the team knows they need to transition from fully hiked to balancing with body movement. If I need help heading up, I will say, “Heel up,” and I will say, “Over flatten,” if I want to bear away. We try to keep the phrases consistent so everyone on the team knows exactly what to do.

Paying close attention to the helm feedback for perfect heel and steering with your weight may just be the “magic” you need to take your sailing to the next level. Go sail blindfolded, rudderless (if you can). Start to understand what neutral helm feels like and then experiment with different angles of heel. You don’t need to know why a specific angle works, you just need to note what heel is fastest for your boat in each condition. In lighter winds, empower your team to balance your boat. In heavy wind, pay close attention to your feel on the helm and work with your trimmer for balance. And in all conditions, have your team pass you concise information, and then return feedback on how the boat is behaving. Work together as a team so you know what you need from each other to sail balanced and keep a constant heel.

Unbalanced (above)

1 Crew Postion: The crew should be constantly moving to keep the boat flat.

2 Sail trim: Since the boat is underpowered, trim for max speed, independent of heel.

3 Rudder Angle: The boat heels and

becomes unbalanced, causing drag on the rudder.

4 Heel Angle: The forward crew should move outboard to flatten the boat.