Current Affairs

Doc: It’s not very often I get to come out on the start boat.

ROB: It’s not very often I get to come out on the start boat, either. In fact, if it comes to a choice, I’d rather be racing. But duty calls.

Doc: So how do you think they all look now with only a minute to go?

ROB: It’s going to be a shambles. A pin-biased line and current running with the wind are going to create a pile of boats that won’t make the pin-end layline. Then someone will panic and tack to port and … What did I tell you? Why is it always Godzilla that creates all the grief?

Doc: You could see that coming, couldn’t you?

ROB: I know a bit about how to sail in current.

Doc: Oh? Do tell.

Rob: I grew up sailing in the upper harbor, so there was always lots of current and often not a lot of wind. You sort of get a knack for it after a while. We’d get these hotshot sailors coming up to our club once a year thinking they could show us a thing or two. But Boris—he must have been in his 80s—was about as cunning as they come, and he really knew how to sail in current. They never beat him.

Doc: So how do you make sense of what he did?

ROB: Boris had a great way of explaining how current worked. You see, racing in current is just … well, there’s no way of making it simple, really. But Boris seemed to be able to explain it to us. He had these little sayings.

Doc: Yes?

ROB: He used to say that there were four things you need to understand if you wanted to sail current well. The first one was about exactly what we saw a moment ago on the start line. “Laylines tell lies when the current flies.” You have to realize—and constantly make allowance for the fact—that current alters the shape of the racetrack.

Doc: How do you mean?

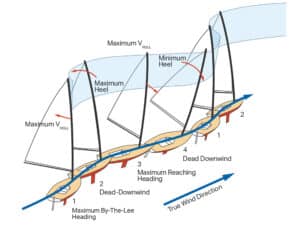

Rob: What you have to remember is you’re sailing around marks that are fixed to the bottom. When there’s current, sailing on the course is like being on a treadmill—and not just walking forward. This treadmill can run in any direction. Let me give you an example. On a start like the one we just watched, because of the current running the same direction as the wind, it seems as though you’re slipping sideways—to leeward—really fast, because you are. It looks as if the mark is moving upwind. It’s not; you’re moving downwind. But that’s what it feels like. If you want to make it past the mark, then you have to set up a lot further to windward. If you use a layline based on where the bow is pointing, there’ no way you’ll make it around the mark.

Doc: Like Godzilla—then they panicked when they couldn’t make it, and tacked on to port. Whammo! There’s carnage at the pin.

Rob: So, any time you have current, it will affect laylines to anything that’s fixed to the bottom, and that means you can’t just point the boat at the mark—the boat will be crabbing one way or the other.

Doc: That’s what happens on downwind legs when boats point straight at the mark, but end up sailing a huge curve.

ROB: Exactly. Sailing downwind, irrespective of where the boat is pointing, you need to work out what course to sail so that the combination of your heading and the current will move you directly toward the mark.

Doc: What is Rule No. 2?

ROB: This one also catches people out all the time. Boris would say, “The less you heel, the more current you feel.” That is, the effects of current change with the speed of the boat.

Doc: [pauses, eyebrows knitted] Go on.

ROB: How often have you seen a boat laying the top mark in adverse current, and then another boat tacks onto its air? The boat slows down and is no longer making the mark. As the boat slows, the current exerts a greater influence on its course.

Doc: I have a great example of that, of how the current effect changes with boatspeed. It was a Snipe race in light wind, and because the breeze was dying, the race committee decided to finish at the wing mark. The current was pushing up the course, against the wind. As the boats came down the final reach, they got slower and slower as the wind dropped, and compensated by pointing lower in order to hold bearing on the finish line. Boats were noticing the effects of the current and sailing lower to get some down-current distance “in the bank.” The problem was, if they squared up too much, the boat slowed down to the point that they stopped stemming the current. In the dying breeze, only one boat realized that they had to stay high enough to maintain speed. They didn’t try to put any “in the bank,” they just went for speed, and managed to sneak across the line before the breeze dropped out.

Rob: I guess that shows how weird it can get. You really need to keep your wits about you, particularly in light winds and current.

Doc: And the third rule?

ROB: The only time you can exploit an advantage from current is when its strength or direction varies in different parts of the course. If the current is the same all over the course, then all you need is Rule No. 1. But usually there’s some variation.

Doc: And to understand that you need to know about the contours of the bottom and the sources of the flow, like at a river mouth.

ROB: Bingo! The funny thing is, when you first think about how current flows, you would logically imagine it to be similar to how wind flows. Actually, it’s quite different. When you compare wind flow to current flow, you’ll see that you get much bigger changes, proportional, in both strength and direction of current flow than you ever do with wind. For example, between neighboring currents, you’ll see speed differentials of 100 percent and direction varying by as much as 180 degrees. You wouldn’t normally see such drastic differences with wind—well, that is except in very light winds with lots of obstacles. I suppose that’s what current flow is most like—a very light wind flowing around lots of obstacles.

Doc: I’m betting that was Boris’ strong point.

ROB: It really was. He knew every little change and wrinkle. When you get the sort of obstacles we had on that track combined with the current generated by tidal flows—which turn 180 degrees every six hours—then you can have current simultaneously flowing in opposite directions on different parts of the course.

Doc: So the rule is stay in the more “helpful” current, i.e., the stuff that pushes you toward the mark, at least a little, and out of the more “unhelpful” stuff. But if it’s all the same—if there’s no variation—then just sail the boat.

ROB: Sounds easy, doesn’t it? As Boris put it, “Current is like an old grudge. The only good current is behind you.”

The trouble is, we think that trying to track the wind is hard, but working out what is going on with the current is harder. Even though we cant see the wind, at least we have sails and wind indicators to give us good information about which direction its blowing. But we don’t have those tools for current. The only way to know for sure what’s going on is to do the research—either with a current stick and fixed markers, information from hydrological services, or long years of experience.

Doc: As in Boris?

ROB: Boris.

Doc: OK. But none of this has been rocket science, really—and you seem to have covered it all already. So what is this fourth rule?

ROB: Ah! Rule No. 4 is a tricky little devil, and it mostly applies in slower boats and light winds. The tricky part is that current effectively creates another wind flow, albeit a gentle one. Imagine you’re sitting in your boat and there’s no wind at all, but a 2-knots current is pushing you along. It will feel like you have 2 knots of wind coming from the opposite direction of the current—apparent wind. That’s why, when you have a strong current flying up the course, it feels like you’re sailing in great pressure; and if the current is flowing down the course in the same direction as the wind, you feel like you’re down pressure all day.

Doc: So my reaction is, “Big deal!”

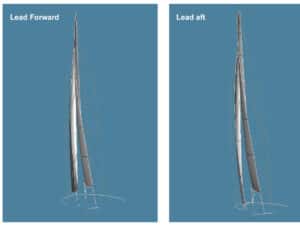

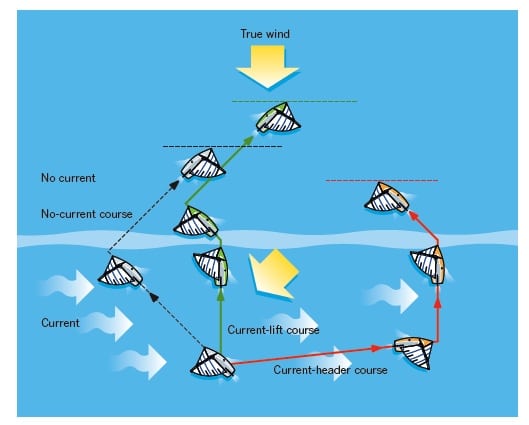

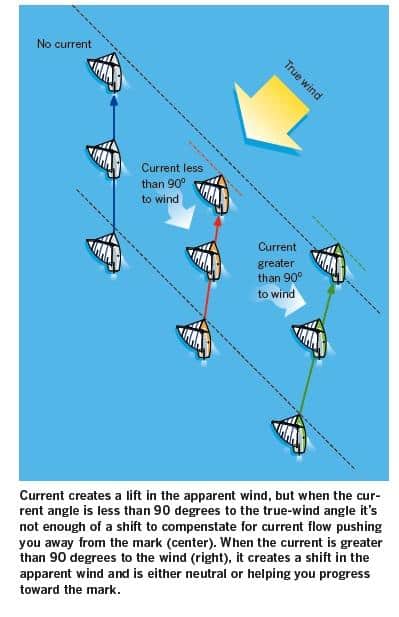

ROB: Well, it can be a big deal in a cross current. A strong cross current creates a windshift—actually it’s only a shift in your apparent wind, but it’s real enough on the boat. Have a look at this picture [see diagram, p. 64]. Because of the current, the breeze is shifted right and strengthened at the bottom of the course, and is left-shifted and weaker when out of the current at the top of the course.

Doc: So the deal in this case is to head left until you are out of the current.

ROB: Yes, and the effect is more significant with stronger current, lighter wind, and a slower boat.

Doc: Don’t you make a gain by taking the stronger current on the leebow anyway? It has nothing to do with a windshift, does it?

ROB: If it was nothing to do with a windshift, then we should see the same effect on motorboats as sail boats. In fact, there’s no difference between going leebow first versus weather bow first—you end making the same amount of progress upwind, albeit you end up a little further to the right in this case.

Doc: OK, so where did the “go for the leebow” belief come from then?

ROB: It’s a bit like centrifugal force—the fictional force. It’s a question of really understanding the angle of the current. Let me explain. For there to be an overall benefit when current is between 45 degrees and 90 degrees to the wind, you have to get enough benefit from the changes to your apparent wind to overcome the fact that the current is actually pushing you backward down the course. Once you get the current to more than 90 degrees to your course axis—or 45 degrees or more to the boat’s course—then you’re laughing.

Doc: So upwind, current anywhere aft of 45 degrees to the bow [i.e., greater than 90 degrees to the wind] is good.

ROB: Yes, because, by definition, it’s helpful current—pushing you upwind. You see, the leebow myth arises because current on the leebow always feels great because you think you’re getting a free elevator ride to windward. But you might actually be going backward, at least in terms of progress toward the mark.

Doc: Did Boris have a saying about that?

ROB: “A skinny leebow is just another way of going slow!”

Doc: But that isn’t a rhyme or a metaphor.

ROB: Yeah, that always bugged me, too.